My Salon editor, Joan Walsh, has generously offered me space for a “rebuttal” of her story and profile. Her story reports on the travails of an ad I have attempted to place in many college papers, questioning the wisdom of reparations for slavery 136 years after the fact. In “rebutting” her article, my task is complicated by two facts. First, though Salon’s editors and I disagree politically, they have given me the very opportunity to have my views heard that so many college papers have recently denied; moreover, in her article Joan has provided a defense of my position in the current controversy. I thank her for this support. We are indeed colleagues and I cherish that fact. In the second place, the only truly negative aspect of Joan’s piece is its somewhat tongue-in-cheek portrayal of me as a publicity-seeking “racial provocateur.” By merely taking the opportunity (and space) to reply as offered, however, I may seem to be confirming the charge.

Let me begin by saying that I am not a racial provocateur and, as I hope will become evident in the course of this reply, I do not have a chip on my shoulder that causes me to seek confrontation with the African-American community. In fact, I do not see myself in confrontation with the African-American community at all. My fight is with the African-American left.

When a well-meaning Democrat in Florida designs a butterfly ballot to help elderly Democrats vote their ticket but inadvertently confuses them instead, and when this becomes a pretext for Jesse Jackson and other demagogues to charge Republicans with a plot to “disenfranchise the descendants of slaves,” that is racial provocation. If you’re looking for a racial provocateur, Jesse Jackson should be your model. Jackson’s strategy is a cynical triad: provocations, negotiations and then “reparations” (for Jackson, of course, and his family and their well-heeled friends).

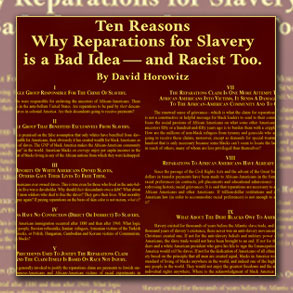

Under the self-serving leadership of Jackson, Al Sharpton and Randall Robinson, the civil rights movement has adopted the triad as its political formula of choice. The reparations claim itself is the work of racial provocateurs — people who want to put race at the center of every political conflict and reveal it as the source of every problem afflicting African-Americans in order to shake out the loot on the back end. The entire thrust of the ad I attempted to place — “10 Reasons Why Reparations Is a Bad Idea and Racist Too” — was to dissuade African-Americans from following the dead-end path of racial provocation down which left-wing arsonists are leading them.

In writing about me, Joan has anchored even her misperceptions in anecdotal data: “‘Now we’re sending the ad to about 100 papers,’ an excited Horowitz says by cellphone, rushing from meeting to meeting.” Well, not “meeting to meeting” exactly. When this conversation took place, I was in my car on Wilshire Boulevard, driving home. The accurate half of Joan’s account is that I was indeed coming from a meeting, as I mentioned to her. It was, as it happens, a five-hour meeting, the only item on my calendar that day. Because it was around 3 p.m., she had to leave our cell conversation abruptly to pick up her daughter after school. As a result, Joan never got around to asking me what my meeting had been about. If she had, it would have thrown some light on her perceptions.

My meeting, in fact, was with three African-Americans who run a grass-roots organization in the inner city. Their operation is an outgrowth of the 1992 Los Angeles riots and is an effort to bring jobs, technical training, “economic literacy” and other financial resources to its inhabitants.

At this moment, thanks to the dead-end, race-polarizing, left-wing leadership of Jackson and others, the project was facing the kind of crisis that similar organizations are facing in inner cities all over the country. It had been receiving, for example, $1 million a year from the Clinton White House; it had been getting valuable political support from Vice President Gore (which it returned to him during his presidential campaign). Now, along with the 92 percent of the African-American community that voted for Gore and stigmatized Republicans as racists, it had discovered what the two-party system is actually about, and why it might not be such a good idea to put all one’s eggs into a single political basket.

My three visitors and I have our political differences. Our meeting began, inevitably, with a discussion of the reparations issue. Fortunately, however, the leader of the organization — whom I have known and worked with for years — was able to form a strong bond with me that none of my “provocations” has affected. He saw early, as others apparently have not, that my criticisms of African-American leaders come from a genuine concern for African-Americans themselves. My reparations argument is really a plea to African-Americans not to let their leaders separate them from the rest of America and then polarize their community against America, which by and large actually wishes African-Americans well.

As a result of our bond, and having aired our differences over the reparations issue, we were able to set to work on plotting a strategy with which to approach the Republican Congress and the Republican White House, through connections that I was able to supply. Our agenda was to get the new administration to continue and extend the support for this project that is now jeopardized, and to build additional bridges across the political divide. I have been working with this group and with similar organizations for many years, just as I have been working with the Republican Party to open its doors and extend its hands to communities and cultures in America that have been left behind.

So much for perceptions of me as an emotionally embittered antagonist of blacks.

Of course, I am something of a political provocateur. Long ago, I resolved that I was going to draw on my experience in the left and fight fire with fire. I was determined to speak to and about the left in its own morally uncompromising voice. I had a rationale for this, particularly where race matters were concerned. Most people are intimidated by the race card when played by the left. Few will take the risk of candor. In these circumstances, a surreal situation has gradually developed until we find ourselves talking now to charlatans and racists as though they were civil rights leaders worthy of respect. Is there any non-black person in America (not ideologically distraught) who thinks of Al Sharpton — a racial incendiary and convicted liar — as a possible heir to Martin Luther King Jr.? Or who does not realize that the very presence of Sharpton does irreparable damage to the civil rights cause?

Yet who outside myself and a “provocative” few would dare to say as much in public? When Sharpton held his Martin Luther King charade at the Lincoln Memorial last August, flanked by New Black Panthers calling for race war, what news media or public figure stepped forward to puncture his balloon? The head of the ACLU took her place on the platform side by side with the racists without even noticing the incongruity. The head of the Urban League was there as well. And so was Andrew Cuomo, then-secretary of health, education and welfare, now a Democratic candidate for governor of New York. And why not? The entire Democratic Party leadership has embraced Sharpton as a “civil rights leader.” Is there any mystery why the African-American community feels OK doing so as well?

That is the situation we find ourselves in, and until it changes, I will continue to speak (as the left likes to say) “truth to power.” I will do it, even though it means being tagged as a provocateur.

I will especially continue to do it on the issue of reparations, which is the biggest shakedown scam of all. Most blacks in America started their post-slavery lives with nothing, and come now from a legacy of centuries of oppression and violence against them. But notwithstanding this past, they have achieved enormous gains in this country. Collectively, they have accumulated more wealth than 90 percent of the world’s nations. In their majority, they are solidly middle-class — and this by American standards, which means they are wealthy by most international standards. Yet on the cusp of success, we do not celebrate their success. Instead we have a black leadership revving up a gigantic grievance machinery to once again dramatize failure — the failure of America in the past; and the failure of a minority of African-Americans, who are mainly fatherless and poor, to take advantage of the opportunities before them. This failure is presented improbably as a continuing “oppression” by the rest of America and thus a rationale for the “reparations” claim. The reparations, however, are not to be paid by slave-owners, or even scions of slave-owners, but by working class Hispanics, Asian boat people, Kosovo refugees, blue-collar whites whose ancestors may have died fighting to defeat the slave power itself, and a hundred million or so others whose ancestors weren’t even Americans in 1865. What kind of lunacy is this? A Time magazine poll shows that 75 percent of Americans oppose reparations for slavery. Don’t you get the idea that black leaders behind the reparations movement want it to fail so that they can keep rage alive and stoke the fires of grievance that have rewarded them so generously in the past?

In asking this question, am I really “inflating black leadership flaws” as Joan maintains? Or telling it like it is?

Finally, I plead guilty to enjoying the attention the ad is getting and the consternation of those editors at campus dailies who have tried to stifle free speech. Who wouldn’t be? Is it important to have two sides to a debate? Is it a national disgrace that without my intervention this dialogue on reparations would never have taken place?

I did not pick Black History Month to launch my campaign. But if I had, what of it? Is Black History Month about history or about the imposition of a party line? Are there two historians who agree on anything? In fact, I wrote my Salon article last summer as a response to the decision by the Chicago City Council to support reparations. The vote was 47-1. That’s some vote for a democracy. Were opponents of reparations intimidated into silence? You bet. Is this an appropriate occasion for outrage? I thought so.

Six months later, I cut the Salon article to single page size — suitable for an ad — when I noticed an Internet posting about a reparations conference that was to be held at the University of Chicago at the beginning of February. I guess it was for Black History Month. It was clear from the announcement that all the participants would be in favor of reparations. Was this stacking of the argument appropriate for a university setting? I didn’t think so. I sent the ad to the Chicago Maroon so those students at the university would get another point of view. The Maroon printed the ad without apology and without incident.

I decided to send 10 ads. I knew that faculty and students on most American campuses functioned under a cloud of intimidation from the left and suspected that no faculty member would publicly present an anti-reparations view. From a career perspective it would be too dangerous. I make no apologies for attempting to run these ads as a way of stimulating a campus debate that couldn’t otherwise take place. Believe it or not, I never dreamed the ad would be turned down at places like Columbia and Harvard, or that the editor of the Daily Cal at Berkeley would apologize for printing it after the fact. His apology (and that of the editor of the Aggie at UC-Davis) was tantamount to saying: We will never air a point of view that offends the campus left, particularly the African-American left. It was this gauntlet that convinced me to send the ad to as many college papers as my resources permitted.

I am thrilled by the result. And why wouldn’t I be? The attempt by the left to turn these campuses into indoctrination centers has been thwarted. A debate has been started all across America on the issues of reparations and free speech. Campus censors are on the run. It is time to say goodbye to campus fascism, no matter what color it comes in. Too many conservative speakers have been driven off American campuses in recent decades; too many newspapers offensive to leftists have been burned in order to deny others access to their ideas. This kind of behavior should be unacceptable anywhere, but especially in a campus setting. Where are the adults? Where was the University of Wisconsin president when his security guards were telling editors of the Wisconsin Badger-Herald (which printed my ad) to lock themselves in their dorm rooms for their own safety? Why weren’t the leaders of the so-called Mulicultural Coalition who organized the thuggery expelled? Why weren’t the students at UC-Berkeley who burned the pamphlets of a visiting speaker last semester suspended and expelled? Why are the university administrators silent during a controversy that goes to the heart of the university mission?

I can tell you this. In the days to come, I am not going to be hiding in anybody’s closet. I’m going to be out there fighting this battle — which I did not begin yesterday, or just to exorcise my personal demons during Black History Month. Ten years ago, Peter Collier and I launched Heterodoxy as a magazine to fight political correctness on college campuses. The center I head was in the forefront of the battle against speech codes. Our lawyers actually forced a University of Minnesota president and a U.C. chancellor to undergo sensitivity training in the First Amendment when they attempted to confiscate a conservative magazine and ban a fraternity whose T-shirt the left found objectionable. The experience was so embarrassing that both universities dropped their speech codes shortly thereafter. But speech codes are only one instrument the left has devised to quash free expression at institutions of higher learning. So when this latest battle is over, I will be finding new occasions to continue the fight, call me what you will, until American campuses are made safe for learning, which means safe for expressing different points of view.