It's a laissez-faire neoconservative's worst nightmare. Just as Republicans take over the presidency, the economy hurtles into free fall, with consumer confidence levels and stock prices racing each other downward in an ever-accelerating plummet. And suddenly, after months of bad-mouthing the economy and claiming that the '90s boom had nothing to do with Clinton administration policies and everything to do with entrepreneurialism, George W. Bush and his aides find themselves in the unlikely position of having to admit that "good public policy" may be necessary to avoid a recession.

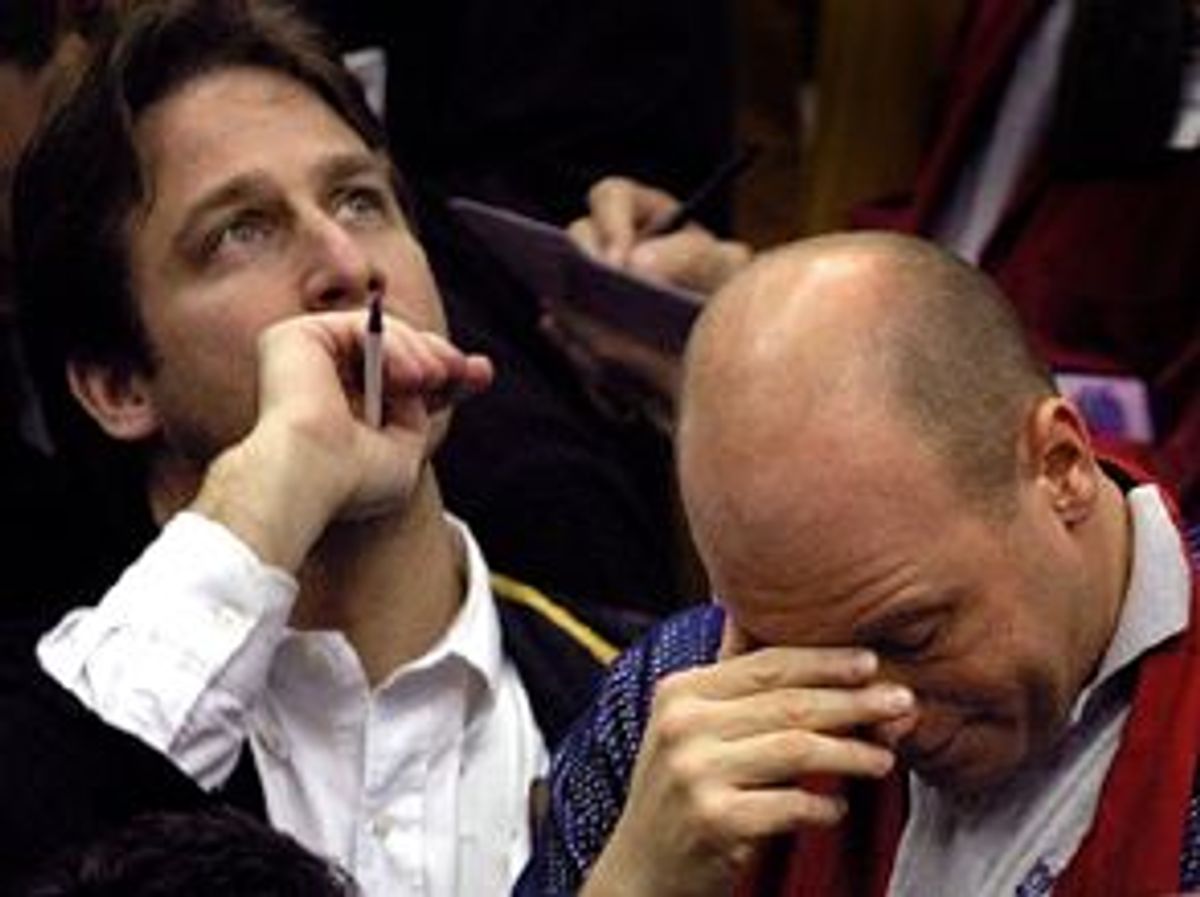

Can it be done? Can Bush be the hero who will lead us out of the current economic darkness? Is there some mix of tax cuts, interest rate adjustments and federal tinkering that will halt the slide? Such questions, certainly, are on the tips of everyone's tongues. But as the markets continue to stumble, a growing chorus of economists is asking another, more pointed question. Never mind whether he can fix what's wrong -- is Bush making things worse?

The current situation is by no means all Bush's fault. It's been commonplace for months to observe that the technology and new economy companies that fueled the '90s boom are now leading the markets down. And it's very easy, and not at all unjustified, to lambaste the new economy leaders, especially the frothy dot-com start-ups that popped up in the late '90s, for their excesses and poor fundamentals -- including, all too often, their inability to turn a profit. There's also little point in denying that when the new economy speculative bubble finally popped, it did so on Clinton's watch.

Technically, the country isn't even actually in a recession, and some stalwarts are still convinced that we may yet avoid the worst. Unemployment is still at historically low levels and inflation is negligible. But consumer and corporate debt is sky high, and the long, slow decline of NASDAQ and the Dow shows every sign of a sustained bear market. Certainly, the "R" word is on everybody's mind. As is the "T" word, for "tax cuts." Because for Bush, that's the essence of good public policy: giving the people back their money.

But are tax cuts in general, and Bush's tax cut plan in particular, the answer? As Princeton economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman observes, the benefits of the Bush tax-cut plan are mostly "back-loaded" -- they won't take effect for years to come and will be of little benefit to anyone right now. If Bush really wanted to stop the oncoming recession, say both conservative and liberal economists, he would push for an immediate -- and temporary --- tax cut. And instead of a plan that puts most real dollar gains in the hands of the wealthy, who are the least likely people to run out and spend their refunds, the best stimulus for our flagging economy would be a tax cut for the poor and working class, the people who would spend it immediately.

Most economists deem it unlikely that Bush will suddenly abandon the constituency that bankrolled his campaign, give in to Democratic opposition and focus a tax cut primarily at the working poor and lower middle class. They are not even sure that any tax cut would make a significant effect. But what alarms them most is that the political strategy Bush has been employing for months to push for the tax cut -- criticizing the current state of the economy -- may well be increasing consumer fears. In effect, the strategy is a self-fulfilling prophecy that could tip the country from a downturn into a full-blown recession.

"I don't know that we've ever before had the experience of a slowing economy where the administration talks it down," says Krugman. "Remember the financial crisis of 1998, which was severe and sharp? Then you had [former Treasury Secretary Robert] Rubin and [Federal Reserve chairman Alan] Greenspan going all out to reassure the public. Now, instead of that, we have an administration that's saying it will get even worse unless you pass our tax cut."

Are we in a recession? Peter Leyden, co-author of "The Long Boom: A Vision for the Coming Age of Prosperity," is skeptical.

"You've got to be very clear that the stock market is not the economy," says Leyden. "We always talk about that when we are talking about the long boom -- a fundamental boom, not an up and down in the stock market.... The macro trends that have been driving the growth of the '90s, like the fundamental spread of computer technology, the telecom buildup, the global integration economy, are still in motion. Maybe they're not as robust as they were in the late '90s, but they're still stable and proceeding at a consistent pace. The pain we have typically associated with recessions -- mass layoffs and horribly contracting economies, huge interest rates -- is not here."

But Leyden is in a minority. Economists of every political stripe see the word "recession" written on the walls.

"We're either in a recession now or heading into one," says William Niskanen, chairman of the Cato Institute and a former senior economic advisor to President Reagan. "The market is almost always a leading indicator and it suggests that things are going to get worse before they get better."

"A lot of consumer and capital spending was tied to the high levels of the stock market," says Jeff Madrick, author of "The End of Affluence." "For the consumer, it's the wealth effect -- if you have a lot of money in the market, you are spending money or you aren't afraid to borrow against your credit cards and house. Now people will still stop doing that. And for corporations, falling stock prices mean that capital is more expensive, so they are cutting back on capital spending. ... Other issues include the Japanese problem, the higher oil prices and of course the stock market is suffering from the absurd speculation on dot-coms."

The Bush administration has loudly and publicly agreed. For months, Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney and their aides have been expressing worries about the economy. In December, Cheney warned that "we may be on the front edge of a recession here." In February, Bush declared, "A warning light is flashing on the dashboard of our economy."

But to economists of nearly every political stripe, the Bush administration's statements have been appalling strategic mistakes. In a calculated attempt to build political support for tax cuts and dump responsibility for the economy on the Clinton administration, Bush is helping to create the very reality that the vast majority of Americans want to avoid.

"In [a potentially recessionary] environment, for a president to be talking about us entering a recession is dangerous, highly insensitive," says Madrick, who also places some of the blame on Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan. "Economies are built on psychology, and here we have the president and vice president talking about recession... But most important, in early January Greenspan panicked and suddenly cut interest rates, which sent a signal to the market and Americans in general that he thought there was something seriously wrong with the American economy."

"Initially, Bush wanted the bad economy to be associated with the Clinton era and was framing it as worse than it was," says Leyden, "and now he is framing things as being worse than they are in order to promote his tax cut to create support and rationale for his tax cut. It was disingenuous, and a really bad move. Because he's drumming up a pessimism about the economy that's a self-fulfilling prophecy."

Even Niskanen, who is adamant in his belief that the economic slowdown started during the Clinton administration, would rather Bush kept quiet about his opinions on the economy.

"He shouldn't comment on the economy by and large," says Niskanen. "It's good to maintain good but private relations with the Fed. He shouldn't argue with or even agree with the Fed in public. It's a dangerous game. His father didn't get it. Clinton learned that early on and Bush Jr. is learning that now. He and Paul O'Neill have to create understanding with the Fed, then leave it up to them to restore demand growth."

Congressional Democrats have seized upon the issue of Bush's rhetoric as well. On Thursday, Sen. Majority Leader Tom Daschle, D-S.D., said at a press conference: "I think we're talking down the economy. And in talking down the economy, I think we're beginning to see the results in the market. The Bush administration has been talking down the economy now for some time."

"But why are they doing that?" continued Daschle. "Well, I think everybody knows why they're doing that. They're doing it for the short-term political gain of passing a tax cut we can't afford and don't need. They're doing it in a way that I think is very, very harmful to the economy."

Would a tax cut really be harmful to the economy? Economists are divided on that question. But they are united on the topic of whether the Bush tax cut, as currently envisioned, would do anything to help the economy escape or avoid recession.

Not a chance.

"Bush's tax plan will have nothing much to do with the recession," says Niskanen. "He hasn't changed the plan, though he has changed the marketing. And I regret that. He's trying to sell his tax plan not as a solution to long-term issues but rather as a way to abort the recession. That's not consistent with what we know about how the economy works, and it invites political risks. It allows Congress to pile on in their own interests, and -- if the economy turns up before the tax cut passes -- it risks losing his primary argument. And it wouldn't do anything for the economy in the near term anyway. Fiscal policy is always too little, too late."

"The tax cut is wrongheaded in terms of helping the recession," says Dean Baker, co-director for the Center for Economic and Policy Research, a Washington think tank. "It's helping the richest people. If we give Bill Gates more money, we're not going to affect his consumption very much. If we give people who are earning far less than that another $10,000 or $20,000 a year, then they'll spend it and the economy will grow."

A tax cut, suggests Madrick, may well exacerbate the lack of consumer confidence in the economy. "I think the Bush administration is undermining confidence because people aren't as dumb as they think they are -- you can't tell them you really need a tax cut because of the recession. People realize this tax cut is a longer-term tax cut, not related to current events, which will undermine the ability for the government to do what it needs to do."

"There isn't a lot of evidence to believe that tax cuts actually act as a stimulation to the economy," agrees Michael Borrus, co-director of the Berkeley Round Table on the International Economy. "And to the extent that tax cuts create a situation in which the government does not pay down its own debt, to that extent we can expect long-term higher interest rates. As the impact of the government's own indebtedness -- our indebtedness to ourselves, so to speak -- plays its way through the system, it's a long-term negative."

So what should Bush be doing? Is there any kind of tax cut that would offer succor to the economy? Niskanen says no -- the only thing to do is let the Federal Reserve handle it. Krugman agrees, for the most part.

"This [the solution to the downturn] is mainly about the Fed's job," says Krugman. "But a front-loaded working class tax cut would help, a temporary cut in the payroll tax, in the child-related tax credits -- something that puts dollars in the pocket of ordinary people. It may not do anything but why not? It couldn't hurt."

But that would still only be a very limited stimulus. If Bush is really serious about improving the economy, says Borrus, "he could engage in a bunch of government spending that's targeted at specific areas, like infrastructure -- utilities, roads. In fact, there's very little the president can do in the short term. The best thing the president can do -- but this is not part of his agenda -- is to prepare us for more rapid and more robust growth when we come out of this recession, however long it lasts."

Leyden agrees: "There's two ways to go with the government surplus. You can actually take that unprecedented amount of public money and start aggressively investing it in long-term strategic things that will make society more adaptable, productive and adept with dealing with the future: Transforming education, moving into new technologies like biotechnology and nanotechnology, or energy technology. You can rebuild infrastructure at a fundamental level. Or you can do what he's doing -- going back to a policy of the past, conceptualized by Reagan, and hand the money back primarily to well-off people that don't really need it on the blind faith that they will invest it in the right places."

But what are the chances of a renewed emphasis on infrastructural spending actually occurring? On Thursday, the Bush administration announced that it wanted to halt the Advanced Technology Program -- a Commerce Department initiative that funnels about $145 million a year into strategic high-technology research efforts. What better evidence could one ask for in trying to determine the priorities of the new administration?

Whatever strategic course Bush and his administration decide to embark on, it seems pretty clear that -- in the words of his father -- slagging the economy just isn't very prudent.

Additional reporting by Janelle Brown, Damien Cave, Amy Standen and Anthony York.

Shares