A glimmer of hope has been beamed into Africa and Asia, where millions have died and millions more expect to die of AIDS. According to a plan announced Monday by the World Health Organization and the World Trade Organization, anti-AIDSW drugs which cost $10,000 a year per patient in America and Europe are to be given free to the poorest victims of the AIDS epidemic.

The two organizations said they will meet in Norway next month with experts and advocates to figure out how to deliver the drugs to people who are dying by the thousands each week. Under the proposed plan, the WTO would work to negotiate patent laws with drug companies and member nations, while the WHO would raise money to pay for production of the drugs and would administer their distribution.

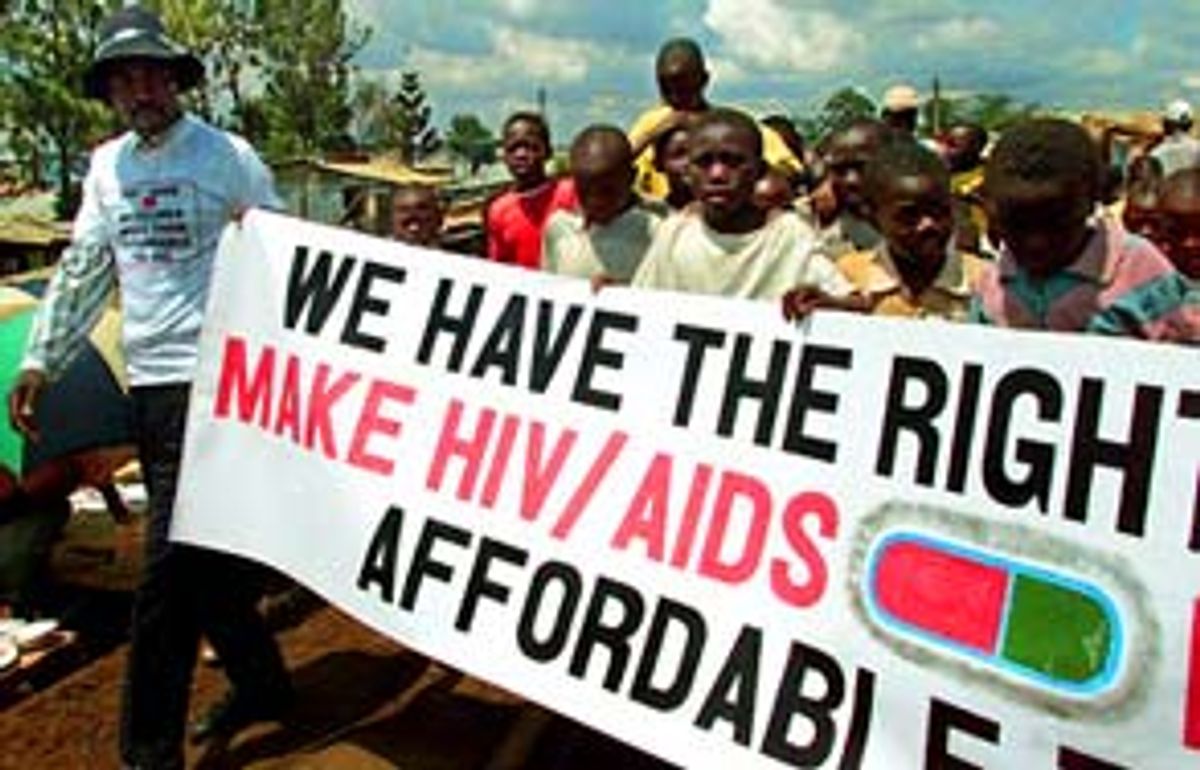

The announcement marks an unprecedented response from drug companies to humanitarian pleas that millions of people not be left to die while life-prolonging medicines sit bottled up on pharmacy shelves. Approximately 70 percent of the world's AIDS cases are in Africa. The WHO estimates that 25 million Africans are infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Currently only 10,000 of them are receiving drug treatment to stem the progression of the disease.

"The world is ready to move on from squabbling about patent issues," said Dr. Nils Daulaire, head of the Global Health Council, which is organizing the April 8-11 meeting in Hosbjor, Norway, titled "Differential Pricing and Financing of Essential Drugs."

"This is not aimed at undercutting pharmaceutical patents," said Daulaire, formerly the top international health official at the U.S. Agency for International Development. Indeed, drug firms plan to send representatives to the meeting to ensure they retain their profitable drug patents in the West, where better-off patients and private and public health insurance plans have been paying full price.

Drug firms argue that they need to recoup the hundreds of millions of dollars they invest in research for these drugs and that they need revenue to create the drugs and vaccines of the future. Rather than abolish patent rights for AIDS drugs, participants in the Norway meeting will try to create a system of licensing the right to produce generic versions at a few cents per pill for those unable to afford the current cost in America and Europe.

The meeting will include representatives of some of the 39 pharmaceutical companies that recently went to court in South Africa to try to prevent distribution of generic drugs produced without permission from the patent holders.

An official with one of the organizations involved in the meeting, speaking on condition of anonymity, said that the pharmaceutical companies are torn between the desire to help people and the fear of what a weakening of their patents -- the fundamental basis of their revenue -- could mean for their business.

The official said that after pressure from the press, the companies finally agreed to take steps to let go of their patents under negotiated terms. "They want to get out from under the image of holding a glass of water while someone is dying of thirst," the official said.

Also speaking on condition of anonymity, a senior official of one of the involved organizations said that the giant pharmaceutical companies finally made the talks possible in the past three weeks by surrendering their legal battles in South Africa and elsewhere to keep all their patents and profits.

Cipla, an Indian manufacturer of generic drugs, proposed selling South Africa inexpensive copycat versions of eight anti-AIDS drugs, including Zerit and Videx -- alarming pharmaceuticals who feared their patents would be undercut. The drug giant Merck followed by saying it would offer the protease inhibitor Crixivan and another anti-retroviral, Sustiva, at its manufacturing cost.

Last week, Bristol-Myers said it would sell Zerit and Videx for a combined cost of $1 per day. While this is a sharp drop from the U.S. daily cost of $18 for the two drugs, most Africans would still be unable to afford them without an international plan of assistance and delivery, Daulaire said.

Subsidized generic versions of AIDS drugs are unlikely to make their way to the United States, however, because safety nets such as health insurance and Medicaid make it comparatively rare for people in this country to be denied drug treatment for HIV/AIDS because of lack of money. But in Africa and Asia medical insurance is essentially nonexistent, and extreme poverty makes paying for drugs out of pocket impossible for most.

Even healthy people in sub-Saharan Africa and much of Asia do not earn much more than $1 a day on average, from which they must provide food and other necessities for themselves and their families. For them, spending $1 per day on medicine is not an option.

Daulaire, whose Global Health Council includes representatives of the world's major health, medical, pharmaceutical and relief firms and groups, said he found that charging even 7 cents for anti-pneumonia drugs in Nepal meant "many could not pay it." If world health agencies can subsidize such a minimal cost, it would put these drugs within reach of the poorest people afflicted.

Profits and public image aren't the drug companies' only concerns. They are also worried that without tightly controlled distribution channels, ineffective doses of the drugs could lead to more resistant strains of HIV. Such public health disasters are happening even now with malaria and tuberculosis, leading the diseases to mutate and the drugs for combating them to become obsolete. That's where the WHO's role is critical: It can make sure AIDS patients receive the drugs -- which prolong lives by several years -- directly and according to the prescribed regimen.

The WTO's end of the bargain may prove easier to resolve. The WTO official noted that pharmaceutical companies may actually be able to increase their profits if the Norway meeting can come up with a way to offer cheap drugs in Asia and Africa while still keeping them at their current high prices in the West. A study by Doctors Without Borders, a humanitarian nongovernmental organization, shows that millions of new customers will come on line if drug prices fall in the Third World, meaning greater profits there, the WTO official said.

Cipla was able to break the monopoly on anti-AIDS drugs because India claimed developing-country status when it joined the WTO. That status gave the nation an exemption for several years from having to respect drug patents, said a WTO official, speaking on condition of anonymity by phone from Geneva on Friday.

The WTO is a treaty organization that requires its 140 member nations, including the United States, to change their domestic laws on patents and trade to accord with those set out by the WTO.

South Africa, which joined the WTO in 1994 as it shifted from a white- to a black-dominated government, did not claim the status of a developing country, which could have given it an exemption from patent infringement. And while South Africa could declare AIDS a national emergency, which would allow it under WTO agreements to buy or produce the cheap drugs regardless of patent prohibitions, last week it announced it would not declare such an emergency. It is possible that the meeting in Norway will resolve the drug companies' suit in South Africa.

To address drug companies' concern about cheap drugs undercutting their profits in America and Europe, the Norway meeting will discuss how to prevent generic drugs "from leaking back from poor countries to rich ones," said a joint statement by the WTO, WHO, GHC and Norwegian Foreign Ministry released Sunday night in Oslo and Washington.

Shares