These are the things that teenage girls do: They play loud music. (If their mothers like Creedence Clearwater Revival, they will probably play Rancid; if their mothers like Rancid, they will probably play Aaron Carter.) They talk on the phone, also loudly, often instead of doing their homework. And probably, if their moms walk by or pick up the extension, just to check, they might overhear something like, "My mom said I could not go to see that (Rancid, Aaron Carter) show because I did not clean my room. My mom is such a bitch." Teenage girls never clean their rooms.

Their mothers sometimes do. When they clean their daughters' rooms, some mothers find notes about missing homework assignments, or boys, or notes that say "My mom is such a bitch." They find teen magazines or porn URLs on the computer. Some find empty Budweiser bottles, condoms, sweatshirts that smell suspiciously like tobacco -- or they find actual cigarettes. The really unlucky mothers find pipes, little foil packages (what is that white powder?) and razor blades, or they read their daughters' diaries and they find out she is shoplifting/drinking/having sex/doing drugs/depressed/anorexic/bulimic -- in short, a generally unhappy kid.

These mothers call their husbands (boyfriends, sisters, therapists) and they say, "What shall I do? She is not the same kid. She is a kid in trouble." They go to their kid and they say: "You are a kid in trouble! You are depressed! You are not normal! You are on drugs!"

And the kid in trouble says: "You hate me! I hate you! I was keeping them for a friend! Don't you trust me? Don't ever come into my room again! You are the worst mother in the world!"

Are you wincing yet?

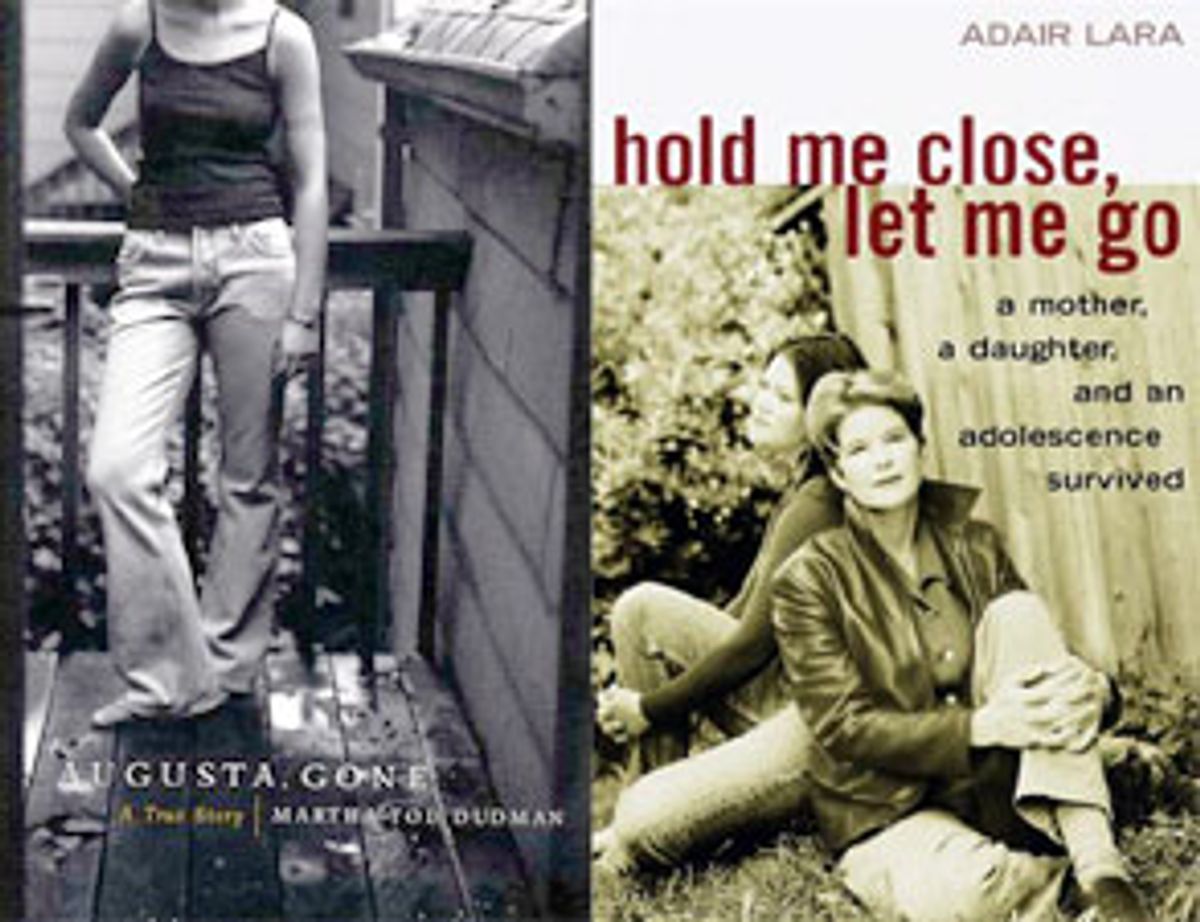

The spring publishing list has brought us two memoirs written by mothers about their demon daughters, both of which cover this familiar terrain in exhausting, excruciating, mind-numbing detail: "Augusta, Gone" by Martha Tod Dudman and "Hold Me Close, Let Me Go" by Adair Lara (who refers fondly to her daughter, Morgan, as her "hellchild"). Taken together, they present a good case for the argument that most unhappy families -- at least unhappy families consisting of mothers and their rebellious teenagers -- are alike, Tolstoy be damned.

Adolescent rebellion -- from playing music that parents loathe to hanging out with strange, spiky-haired boys to experimenting with sex and drugs and alcohol -- differs more in degree than it does in kind. On the one side is a screaming teenager who insists that she is fine, she is in control, she is independent, she is misunderstood. On the other side is a mother who insists that her daughter is not fine, who fears for her safety and who also sometimes screams. Both mother and daughter love each other and hate each other in equal measure. Both are prone to fits of drama and exaggeration. As a reader, it is difficult, if not impossible, to sift out a true and accurate account of what actually happened during the teen years of these girls. But truth and accuracy, in these books, are nearly beside the point. It's more interesting to look at what these mothers think happened to their daughters than it is to concern oneself with whether they are correct.

Dudman is a single mother and a former radio station owner; she lives in Bangor, Maine. Lara is on her third marriage. She lives in San Francisco, where she is a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle. Both of the authors are 49 years old and each has two children -- an older daughter and a younger son. Both are well-educated and middle to upper-middle class.

These are not pleasant books. Reading them is about as much fun as fighting with your own teenage daughter or refereeing the birthday party of a friend's teenager when 50 percent of the teenagers are on crack, and the other 50 percent are lying about who is and who isn't on crack. By the time you are done, you just might be tempted to smoke some crack yourself.

Of course, these books are not meant to be pleasant. They can be read as true-life horror stories. (One reviewer dubbed them the literary equivalent of "When Animals Attack" or "Great Highway Car Wrecks" and warned parents of small children not to go near these books, lest they fall into a state of despair.) They are marketed, in part, as literary parenting manuals, the kind of books that mothers press into other mothers' hands like cures for colic and diaper rash, the kind of books that bad girls — some time between their 18th and 21st birthdays — will give to their good mothers on Mother's Day, as peace offerings.

In an interview with Publishers Weekly, both the authors and their respective editors talked about the dearth of books for mothers of difficult teens written by mothers who had lived through the experience. This was a special-interest niche that both authors hoped to fill.

"This was a rare find," said Denise Roy, Dudman's editor at Simon and Schuster, who won the rights to "Augusta, Gone" in what she describes as a hotly contested auction. "How to deal with teenagers is a perennial question in our society, and there aren't many people who can write this honestly about it."

Mothers who turn to Lara and Dudman as surrogate therapists will find a certain amount of bare-bones advice in these books. Their message is: Love your daughter. Their message is: Mother knows best. Their message is: Good girls grow out of it. (Lara's therapist even provides a helpful timeline: If you are going to have a hellchild, she will usually emerge in March of seventh grade and recede sometime during her senior year of high school. If your kid is nearing the end of sixth grade, stock up on breathalyzers. Now.)

But I did not find these books at all reassuring. I did not see them as horror stories because, mostly, I was not shocked by the daughters' behavior, which for the most part is a familiar litany of sneaking out, smoking, drinking and dabbling in drugs. (Although Dudman's memoir was heavily marketed as the book that the mother of Alice of "Go Ask Alice" would have written, neither Augusta nor Morgan seems to be up to the task of being a spokesgirl for the drug-addled hellchild.)

I did not see them as useful documents from a parenting perspective, mostly because I found myself sympathizing more often with the bored, misunderstood, supposedly fucked-up adolescent girls than with their mothers, both of whom seemed to me to be suffering from the same kind of maternal myopia that makes mothers believe that their children are the brightest and most beautiful. (Of course, in this case, the sentiment is inverted: These women seem to believe that if their child is a pathological fuckup, she is the valedictorian of the pathologically fucked-up-girl class.)

Instead, I saw these books as frighteningly accurate -- and often unwitting -- primers in exactly how and why conflict between teenage girls and their mothers is inevitable. Simply put: Being a good girl is boring. Being a bad girl is exciting. Being a good mother is excruciating.

Both mothers, who were themselves bad girls, know the lure of rebelling against the predictable boredom of good girlhood. This is what makes these books such schizophrenic portraits of family life. As former hellions now firmly ensconced in stable, comparatively boring middle age, both mothers seem intoxicated with their daughters' youth, beauty, sexual gumption and general badassedness, envious of their freedom and in awe of their daring. (When Morgan is chastised for leading a renegade discussion of "Animal Farm," a book she has not read, during her English class at Lowell, a strenuously academic San Francisco public high school, Lara writes: "I fought a smile, felt pride struggling up despite myself. Secretly, I thought that Lowell, with its legions of meek, accomplished students who did A work but had to be prodded into opening their mouths, could use a few more Morgans.")

At the same time, as mothers deeply mortified to be raising bad girls, they see it as their duty to curb or cut off completely their daughters' sexuality, restrict their freedom and keep them safe.

The authors' pasts collide with their maternal self-consciousness and explode in narcissistic guilt. Their daughters' teenage years so closely parallel those of their mothers that one can certainly see why the mothers suspect that their daughters' rebellion must have something to do with them. ("She's a bad girl," writes Lara. "And I made her. If a factory is judged by its product, I'm a bad mother.") But the parallels are so striking that it's also difficult to imagine that these mothers see anything but photographic reflections of themselves and their families in their daughters. And this just may keep them from understanding anything about their daughters, as individuals, at all.

Lara became pregnant at 16 (though she aborted the pregnancy) and got married by 17, moving out of her mother's house before she finished high school. She was the only person in her family to go to college, and still has a marked distaste for her extended family's chain-smoking, trailer-dwelling, undereducated lifestyle, though she loves them and spends time with them all the same.

Lara's daughter, Morgan, also becomes pregnant at 16. But even before her pregnancy, Lara and her family seem to have a weird sort of hysteria about Morgan's sexuality. Lara's sisters say they don't trust her at home around their husbands and boyfriends ("Mom," cries Morgan, "I can't help it if I have big boobs!") and Morgan's stepfather becomes disgusted when Lara tells him that Morgan is no longer a virgin.

For Lara, Morgan's pregnancy immediately conjures up images of her own sisters, who became teenage mothers, never went to college and ended up as career waitresses: "I was tormented by images of Morgan with flyaway hair, holding a toddler by the hand and a baby at the breast, coming home from her job at Denny's."

Lara's response to her fears about her daughter's potentially bleak future is to make it potentially even bleaker. She refuses her daughter all financial support and plans to kick her out of the house if she continues the pregnancy. (By this time, Morgan has already lived with a series of Lara's relatives, friends and colleagues, on and off since she was 15, when her mother decided she could no longer deal with her rebellious daughter.) Morgan leaves, but finally agrees to have an abortion after her grandmother tells her that no one in the family will respect her or speak to her again should she continue the pregnancy.

As a teenager, Martha Tod Dudman had sex, smoked pot, dropped acid, was not allowed to graduate with her class at the prestigious Madeira School and ran away to live in a Tenderloin tenement in San Francisco at age 17.

Dudman's daughter, Augusta, wears her mother's hippie clothes from the '60s, smokes pot and does acid. To Dudman, Augusta's pot smoking is different from her own: "I know it's not the gentle grass of the sixties. They treat it with something now, don't they? It's powerful." When Dudman's ex-husband tells her that he believes their daughter when she says that she finds drinking disgusting and has only smoked pot once or twice, Dudman thinks, "With the drugs, she had to have lots of them. Had to have every kind. Had to take everything. If she could have, she would have smoked fifteen cigarettes at once. I know because I was like that, too."

Dudman eventually decides to ship Augusta off to a wilderness treatment program in Oregon. It's hard to say whether this makes the situation better or worse. Augusta is so miserable that she slashes her wrists in the first few weeks. And when she gets the chance, Augusta busts out of the treatment center and, like her mother before her, runs away to San Francisco. (This really sends Dudman over the edge: She and another parent send both the FBI and a hired thug to hunt down their daughters and bring them back into captivity.)

Both girls survive their teen years and, eventually, according to conventional definitions, thrive as successful young adults (albeit successful young adults who are on book tours as the poster children for their mothers' memoirs). Augusta, now 18, is living in San Diego with her own apartment, a job and dreams of opening an art gallery. Morgan, now 22, has just graduated from UC-Santa Cruz with a degree in philosophy. But it's difficult to tell whether these girls "survived" because or in spite of their mothers' overwrought interventions.

Did Morgan really need to spend two years of her adolescence shuttling between the homes of anyone who would take her? Did Augusta really need to spend six months of her life and $50,000 of her mother's money in a lockdown program? It's difficult to say. The closest thing to an evaluation that either girl receives is being diagnosed with "oppositional defiance disorder," a supposedly grave illness with symptoms so vague as to basically serve as a definition of adolescence.

Perhaps the biggest obstacle that teens face is the fact that every parent was once a teen. And the memories these parents have of their own adolescence make it virtually impossible for them to see the teenagers in front of them.

It happened to me, too. Although I am a mother of a preteen, who at 11 is about 12 months away from the proscribed hellchild age and already showing signs of rebellion (she spends all her time on the phone or in chat rooms, swaps her Aaron Carter for my Rancid and has started to tell me she hates me), I couldn't identify with these mothers. But I could identify with their daughters.

I spent the '80s watching my friends being shipped off to bad-kid boot camps by their middle-class parents until they ran away or reached the age of majority or returned as criminals or cretins. I can't read about institutions for teenagers without hearing the lyrics to "Institutionalized," the Suicidal Tendencies song that we played on our car stereos during that decade. ("I'm the one who's crazy?/When I went to your schools, and your churches and your institutional learning facilities?")

When I hear of runaway kids, I think of all of the kids who lived in my mother's basement throughout high school because their parents kicked them out of the house. I think of the ones whose parents later called the police to come get them, even though when we called them to tell them where their children were, they said, "Keep them."

When Morgan, who is back in school and getting A's, asks to drop out of the Narcotics Anonymous program, she tells her mother, "I don't want to be here. I'm not a drug addict. Even when I was doing drugs, it was never my idea. I would have just as soon gone to a movie." I believe her. I know kids like that.

You would say those are my biases. I am aware of them, and I am certain that they will color my interaction with my own daughter as well.

As long as middle-class girls know what a good girl is supposed to act like, a certain percentage of them -- often the brightest, the prettiest and the most original -- will decide that being a bad girl is more interesting. Mommy's little monster is created by Mommy's little princess.

It's not that these aren't potentially serious activities; they are. Some kids start out with drugs and sex and end up college-less, jobless, homeless and even dead. But there are other kids who smoke marijuana on weekends, do acid in the park, run away to San Francisco at 17, get pregnant at 16 or married at 18 and end up being fine, upstanding, middle-class and upper-middle-class professionals. Some of them may still smoke a joint on weekends, or do ecstasy at a New Year's Eve party or acid at Burning Man. Some of them may end up doing nothing more than having a glass of wine with dinner.

And some of them may end up as newspaper columnists, as radio station owners or on their mothers' book tours. Morgan, Lara wrote in a recent Chronicle column, is already choosing her outfits for talk shows. Lara envisions the two of them "chuckling about her terrible teen years with the local reporters over eggs Florentine."

Shares