The 2001 baseball season is opening under a cloud. Everyone knows that the basic agreement between the players and owners is up at the end of the year, and that there is as yet no substantial reason to believe the game won't be crippled by the same nearly disastrous work stoppage that wiped out the World Series in 1994.

Everyone knows that the vast difference in the amount of local TV revenue collected by teams such as the Yankees and Braves and Dodgers on one end and teams like the Twins, Mariners and Reds on the other has ruined competitive balance in baseball and spoiled the season for most teams even before the season begins. Everyone knows that the orgy of home runs and run scoring over the past couple of seasons is turning fans off. We all know that big salaries like the $252 million to Alex Rodriguez are bankrupting teams.

Well, we don't know as much as we think we know. In fact, what we don't know could fill up a season. The first item, the no basic agreement leading to a possible work stoppage: That could happen. And the main reason it could happen is the mistaken perceptions about the rest, all of which can be laid at the feet of baseball's management, aided by a gullible press.

There is a vast difference in the local TV revenues of teams in big and small cities, but so far it hasn't done much to ruin "competitive balance." The strange-but-true fact about the current state of major league baseball is that it has never been more competitive. Either the so-called have-nots have been trying harder or some of the haves have become too complacent, but whatever the reason, big league baseball, the only big pro sport without major revenue sharing and a salary cap, has somehow attained the ideal of parity and competitive balance that other sports have drooled over.

Last year, for the first time in baseball history, every team in both leagues finished with a winning percentage over .400 and under .600, numbers that are all the more remarkable when one realizes that there are 30 teams out there. It doesn't seem possible that, given such a large number of teams, a few or a couple or at least one didn't rise high above or dip well below the median.

And this wasn't a fluke. Far from it. It was the end result of a "parity trend" that has been following baseball around for more than a decade, and that the 1999 season helped obscure. In '99, three teams finished above .600 and below .400; there had not been six or more teams to finish above and below these marks since 1985, when there were eight (four of each). In fact, since '85, only in 1988, 1995 and 1998, when there were four (two above .600 and two below .400 each time), have there been more than three. There have been 10 seasons since '85 in which two, one or no teams finished over .600 and under .400.

Competitive balance is what they're supposed to have in the NBA, where every season some team threatens to finish under .150, where the Los Angeles Clippers, playing in one of the biggest markets in the country, remain unable year after year to even come near a playoff net so wide it would trap Moby-Dick. Competitive balance is what major league baseball has had for nearly two decades, and no one seems to have realized it yet.

Competitive balance is here all right. It shouldn't be, not with the Yankees and Braves and Dodgers and Cubs (yes, the Cubs) playing in huge markets with enormous TV revenues compared with the league's smaller-market teams. Baseball doesn't deserve to have competitive balance, not with an ownership ruled by a greedy oligarchy that constantly browbeats the weaker franchises into actions that run blatantly counter to their best interests, and the game's. But it's there, and this year that's going to be more evident than ever.

I know what you want to say. It's probably what I'd say if I lived in Minnesota or Pittsburgh or Montreal (except there I'd have to say it in English and French): "How can you have competitive balance when the Yankees win every year? How can you talk about competitive balance the year after the Yankees and Mets played in the World Series?"

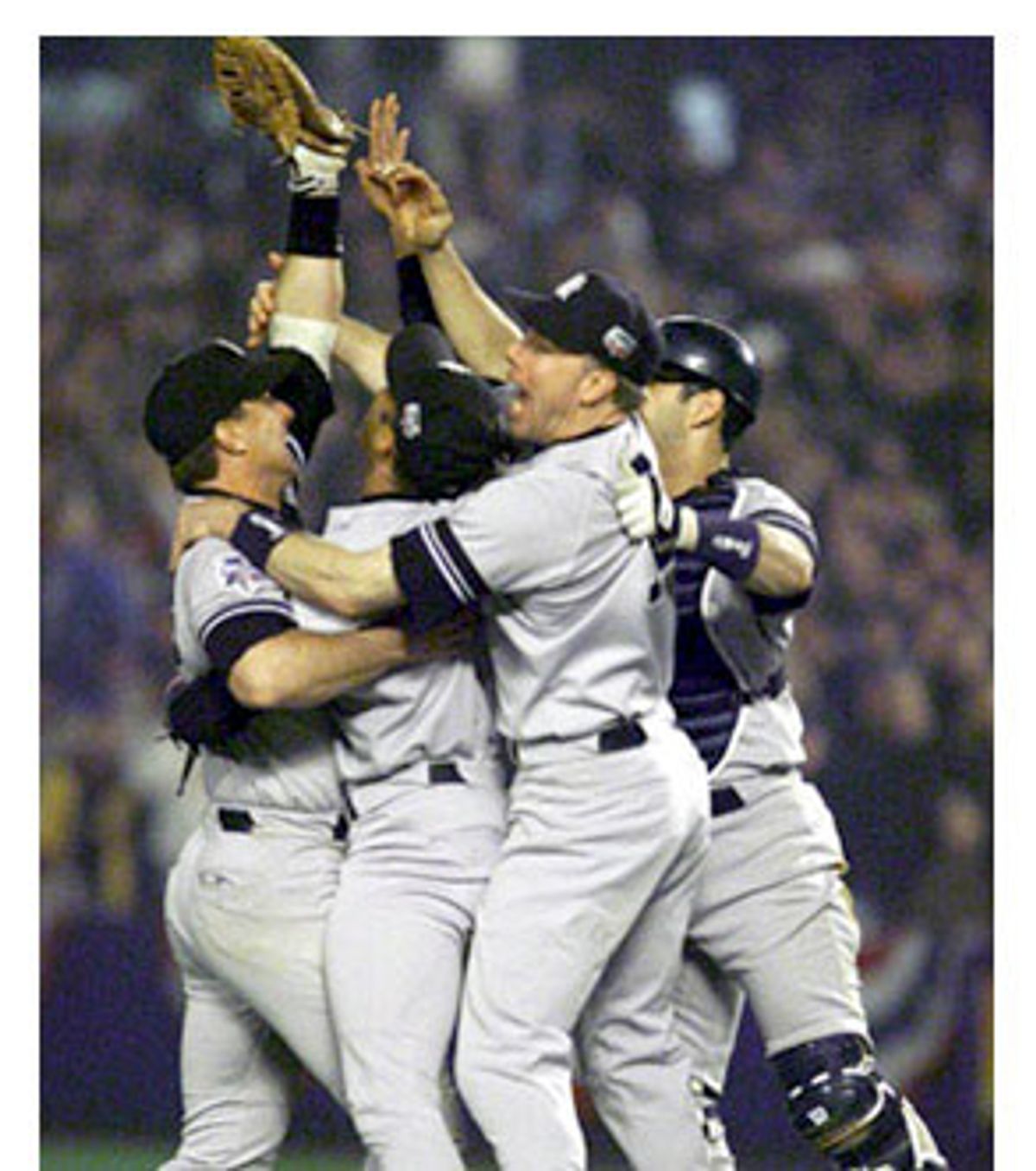

Well, first of all, it would lead to a better understanding of what's going on in major league ball right now if we stopped seeing the Yankees as a symbol of all that is evil in baseball instead of what is right with it. In 1998 the Yankees had the greatest team in baseball history, period. But in the other three World Series years under Joe Torre they have barely been better, if at all, than several other teams in the playoffs, both large and small market.

Take last year's American League pennant. That's what four other teams, all with better records than the Yankees, could very easily have done. Two of those teams, the A's and the Mariners, were the Yankees' playoff opponents, both from small markets and both with four more wins than the Yankees in the regular season. Did the Yankees squeak by both of them in the playoffs because they had overwhelmingly better talent, or because they played like a cohesive unit and made the big plays?

Likewise the Mets: Who really thought around Labor Day that the Mets were the favorites to take the National League pennant? It was obvious to me that the Braves were a better team, and it was equally obvious that both the Cardinals and the Giants -- who had the best record in the major leagues -- were better teams. The Cardinals, of course, simply fell apart, while the Giants -- well, I don't know what happened to the Giants, but I know they should have beaten the Mets. If you had taken a press box poll a week before the playoffs, the overwhelming favorites to meet in the World Series would have been the A's and Giants.

And why not? They certainly had the best young pitchers and the best front-line talent. (These two teams gave us the most valuable players for both leagues.) And, remember, the A's and the Giants were teams that only a couple of years ago were supposed to be in the ranks of small-market have-nots that couldn't compete against the big boys, particularly because they had to split the fan base in the Bay Area. Well, guess what: That turned out not to be true. When both teams started winning, it didn't divide the fan base, it multiplied it. And you know what? The Giants and A's stand an excellent chance of winning their respective leagues this season; for many, they are the preseason favorites.

Nonetheless, the sports press remains fixated on the Yankees, who committed the cardinal sin of purchasing a free agent, Mike Mussina, from the Orioles, and the mighty Texas Rangers, who took Alex Rodriguez from the hapless Mariners with a $252 million contract. It's amazing how quickly the Yankees and Rangers became villains in the press for doing no more than trying to improve their teams.

Only a couple of short years before, the Orioles, because of Camden Yards and a wealthy new owner, were supposed to be a big-market club. But they've mismanaged their resources, and now the Yankees, who had built their recent winners on minor league prospects and sound fundamentals, signed a free agent from their roster -- their first, by the way, since Dave Winfield 20 years ago. So the Orioles have suddenly become a small-market team and the Yankees bad guys.

I doubt if many people regarded the Rangers as much more of a market than Seattle before the A-Rod deal -- at least not in the last six seasons, when the Mariners posted the better record three times -- but all of a sudden it was Texas "stealing" Rodriguez from poor Seattle. You had to read to the end of the stories in most cases to find that Texas created the money to buy Rodriguez with a slick cable deal put together by A-Rod's agent -- a deal that would not have been possible if Texas had not agreed to use the new money to buy him. In other words, the deal cost Texas nothing at all, and any extra tickets (they've reportedly sold 600,000 more than last year so far) and T-shirts and hot dogs they sell are just gravy (to say nothing of any extra wins).

So what am I going to do, sit here and tell you that on Opening Day all 30 teams have a good shot at winning this season? Hell, no. Minnesota and Montreal and Pittsburgh and Tampa Bay and San Diego are going to suck. There are 30 teams out there, and somebody, most somebodies, are going to lose. Tough breaks.

There are too many teams anyway; baseball could easily do with four or five or six fewer. I don't want to see any more bullshit work stoppages justified because the owners needed to make Kansas City competitive, as if they gave a shit about Kansas City before the time came to bargain with the players union. Anyway, if you want competition, you'll find it in baseball this year more than in any other professional sport, and that should be enough to keep you happy.

Oh, did I mention that the Yankees and Royals were separated by just 10 games last year?

Everyone knows, or should know, that there are eight bona fide Hall of Famers among us: Cal Ripken Jr., Rickey Henderson, Gregg Maddux, Mark McGwire, Barry Bonds, Tony Gwynn, Roger Clemens and Barry Larkin.

What, you didn't know about Larkin? You should. He has played for 15 seasons, he has a batting average of .300, he's an 11-time All-Star, he has an MVP award and a World Series ring and he was won half a ton of Gold Gloves. He was nearly as good a fielder as Ozzie Smith and is a more productive hitter; he's one of the six or seven best shortstops in National League history.

OK, that's settled. Let's move on to guys who are on track for the Hall of Fame. There are 18 players in this category, and they are Nomar (like Madonna, he doesn't need a second name), Pedro Martinez, Manny Ramirez, Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera, Alex Rodriguez, Ivan Rodriguez, Mike Piazza, Randy Johnson, Chipper Jones, Andruw Jones, Tom Glavine, Sammy Sosa, Ken Griffey Jr., Larry Walker, Jeff Bagwell, Vladimir Guerrero and Edgar Martinez.

You didn't know about Edgar? You certainly should. He is the best hitter of this generation, with a career on-base percentage just a couple of points under Ty Cobb's. He has led the league in hitting twice and on-base percentage three times, and his career slugging average is higher than Sammy Sosa's. True, he's a hard sell because he hasn't played the field much in recent years, but one could argue that by DH'ing he has contributed more to his team than Frank Thomas has contributed to his by playing first base.

By the way, by "on track" I mean "if they continue at their present rate." Clearly this doesn't mean the same thing for Edgar Martinez, at age 38, as it does for Andruw Jones, at age 24. For Martinez, one more really solid year will do it. For Jones, at least 10 additional seasons are going to be needed.

The only other player on the list who might seem questionable is Glavine, but he shouldn't be questionable. Glavine, at age 35, has won "only" 208 games, but clearly that is because starters in the age of five-man rotations aren't going to win as many games as pitchers who pitched in the eras of four-man rotations. It's only a matter of time till the HOF voters understand this, and when they do, Glavine's credentials will be obvious. He has led the league in wins five times; that ought to be enough of a recommendation right there. Really, he belongs in the "Already In" category more than this one, but 16 or 17 more wins should make his case obvious.

That leaves by far the most interesting category, Players on the Cusp. These are the guys who have some credentials but need to step it up for a few more years to nail down a plaque. I'll name eight of these: Roberto Alomar, Mike Mussina, Bernie Williams, Juan Gonzalez, Jason Giambi, Andy Pettitte, Frank Thomas and Fred McGriff.

Which of these is the most controversial? Alomar, probably, because of the spitting incident, but in terms of merit he deserves to go all the way to "In." Alomar is a 10-time All-Star with nine Gold Gloves, a career batting average of .304 and the highest stolen base percentage in baseball history. There is no question that on merit alone he deserves to be in; he is the best American League second baseman since Charlie Gehringer more than 60 years ago. How could Nellie Fox be in and Alomar out?

Pettitte and Williams? Obviously they get points as mainstays of a dynasty that they would not get on losing teams -- but then why should they be punished for winning? Williams, at 32, would need an additional four or five years at the same pace as the last few, and another batting title. Pettitte would need to continue to be Pettitte for about eight or nine more seasons. I have no idea if that is plausible, but he's just 29 now, and how many starting pitchers win 100 games (against just 55 losses) in their first six seasons?

Gonzalez, clearly, needs a sharp reversal of form to his earlier self, and he'd better hit a ton, because he can't do anything else. That's my argument against Thomas: Outside the batter's box, he's not just mediocre, he's a definite liability. Sure, he has the stats, but he'd better keep piling them up. I've always thought McGriff's chances were better: With two home run titles and 417 total, I think he's more likely to be a potent hitter at age 39 or so than Thomas at, say, 34. We'll see.

Meanwhile, let's see if Giambi, who had one of the great seasons in the American League over the past two decades last year, makes his move. I was amazed to look at Giambi's entry on Total Baseball and see that he's 30 years old; I thought he was 25 or 26. In his last two seasons he has hit 76 home runs and driven in an amazing 260 runs. Obviously, he needs to do that for about five more seasons (by which time he'd have about 340 home runs) to make a run, but if he wins another MVP award I'd say he's on track.

That leaves Mike Mussina, who, over the past nine seasons, has been, quietly, one of the seven or eight best starters in baseball history. His 10-year won-lost percentage, .645, is amazing, particularly as he has done it for otherwise mediocre teams. In fact, ranked by won-lost percentage in relation to his team's mark he is third on the all-time list, behind Clemens and Walter Johnson and just ahead of Robin Roberts. Think he'll do better or worse on the Yankees?

Shares