As California faces up to U.S. Census data that confirms what Los Angeles already knew -- whites are no longer the state's majority population, and the future belongs to Latinos -- the big question about next week's mayoral election might seem to be whether this city will elect its first Latino mayor in more than 100 years.

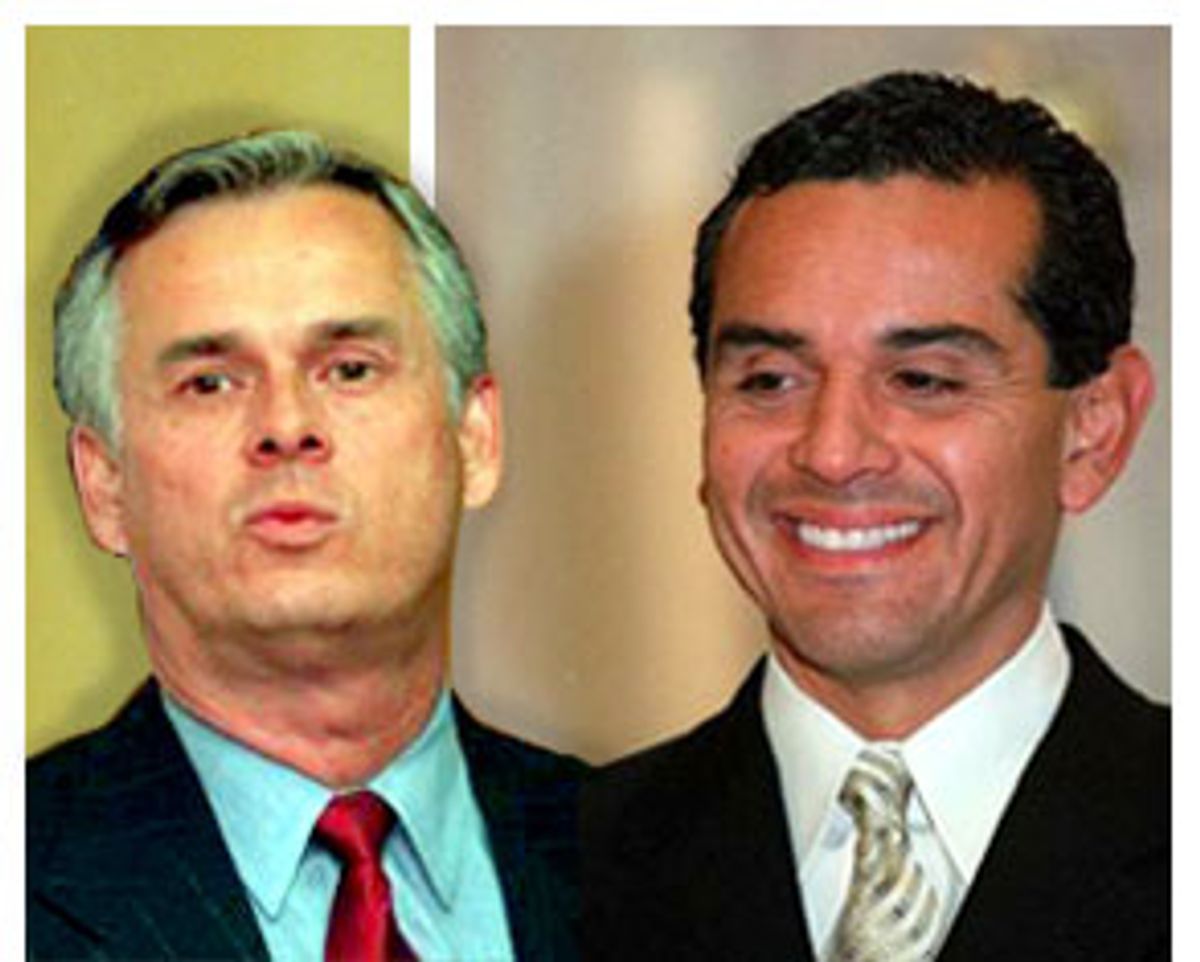

But focusing on race and ethnicity obscures the bigger issues at play as L.A. decides who will succeed its first Republican mayor in 30 years, Richard Riordan. Clear racial conclusions about the April 10 election are elusive: The "black" candidate -- the one with the most African-American support -- is a white guy, City Attorney James Hahn. The leading Latino is former Assembly Speaker Antonio Villaraigosa, but Villaraigosa's Latino base is being eroded both by Hahn and Rep. Xavier Becerra. A recent Los Angeles Times poll found Hahn had as much Latino support as Villaraigosa -- both at 19 percent to Becerra's 30 percent. But while he may have more support among Latinos, Becerra has not been able to build the coalitions Villaraigosa and Hahn have.

The surprises continue: Although there is a woman in the race, California State Controller Kathleen Connell, the National Organization for Women is supporting Villaraigosa. And despite two Jews running for mayor, City Councilman Joel Wachs and developer Steve Soboroff, the Jewish Journal's Marlene Marx recently wrote, "A good case could be made, and many in the Jewish community are making it, that Villaraigosa is the 'Jewish candidate.'" Wachs turned himself into the only gay candidate with a surprise jump out of the closet in a television interview just before declaring his candidacy for mayor in 1999.

Villaraigosa's supporters are touting him as the 21st century Tom Bradley, the iconic black mayor first elected in 1973, who spent 20 years in City Hall. But his struggle to secure his Latino base shows that Latinos are far less likely than blacks to elect one of their own. L.A.'s mayoral election may herald a new, post-race political future, in which the issue of racial identity and allegiance is so complex and cross-cutting, for every candidate, that it becomes a non-issue.

First and foremost, Villaraigosa, a former teachers' union organizer, is the labor candidate. "This race is a tale of two cities," says Martin Ludlow, political director of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor and a former Villaraigosa staffer. "People like to say it's about race, but it's not. It's about class. For the national labor movement, there is not a more critical municipal election that the L.A. mayor's race."

If the election to succeed Riordan is in fact more about class than race, then it is also a referendum on the growing power of organized labor in this city. The question may be less whether Los Angeles is ready to elect a Latino mayor than whether it's ready to elect one who is being propped up by organized labor to the tune of $1 million.

Republicans, of course, say no. "At some point, his opponents are going to ask the question: 'Do you want a union hack as mayor of L.A.?'" says former Riordan political strategist Arnold Steinberg. There is a GOP candidate in the race, but the coalition of voters that backed Riordan is now split, between the Republican candidate Soboroff, Wachs and Connell. Many of Riordan's top financial backers are also behind other candidates.

Good polling data for the race is at a premium. The race has proven difficult to measure in part because the voting universe is expected to be so small. The Times poll shows Hahn leading with 24 percent of the vote, and Villaraigosa and Soboroff tied for second with 12 percent. A recent poll by local television station KABC showed the labor favorite surging into a strong second place, close on Hahn's heels. The top two vote getters will head into a June runoff if nobody gets 50 percent, which seems likely.

Villaraigosa's campaign events enjoy an energy that's been missing from the other campaigns. Some of it is provided by union members, who often turn Villaraigosa events into raucous rallies. But much of the energy comes from the candidate himself, who is Clintonesque in his ability to charm on the stump. At a recent South Los Angeles campaign event, Villaraigosa takes his wireless mike and strolls through the crowd, giving a barn-burner of a speech that has the crowd erupting in choruses "amens" and "that's right" between thunderous rounds of applause.

"I'm going to restore trust in the LAPD," he says. "We're going to end this culture of us vs. them; of people who came in from Iowa, fell off a turnip truck and think they're in the Marines. We're going to make the police accountable to their communities."

In a field of candidates sensitive to the whims of secessionists in both the San Fernando Valley and the South Bay, Villaraigosa is the head cheerleader for Los Angeles unity. "People want to connect with each other," he says in an interview between campaign stops. "I understand there's a lot of frustration that communities around this city feel with City Hall, and I want to create the opportunity to build a shared community. But they want to come together, and I want to be a conduit for that."

Unfortunately for Villaraigosa, he also shares with Clinton a common history of philandering, which has cost him political allies in the past, and may cut into his voting base come Election Day, particularly among Latina women.

If elections were won on endorsements alone, it would be Villaraigosa in a landslide. In addition to the backing of the L.A. County Federation of Labor, Villaraigosa has received backing from Gov. Gray Davis, the Democratic Party, County Supervisor Gloria Molina and members of the business elite like Ralph's Supermarket magnate Ron Berkle and Univision owner Jerrold Perenchio, to name a few.

But in this extremely fluid political climate, the front-runner for now is still Hahn, the scion of the city's most famous political family. Hahn's father, Kenny, represented the largely African-American neighborhoods of South Los Angeles on the County Board of Supervisors for four decades. Mere mention of the name Hahn is golden in the city's black neighborhoods, and his 20 years as city attorney and controller have given him a name identification other candidates are still struggling to build.

The April 10 election could serve as a marker of the vast changes over the past eight years -- some demographic, some political, some economic -- that have created tectonic shifts in the city's political landscape since 1993. That was the year Riordan, a Republican businessman who had never held elected office, became mayor of this solidly Democratic city.

In the eight years since Riordan was elected, a boom in high tech and entertainment jobs has replaced defense-driven industry as the city's major economic engine. Meanwhile, the voice of local neighborhoods has grown louder as secessionist movements in the San Fernando Valley, Hollywood and the South Bay continue to gain momentum. Police conduct continues to be a key issue, but the dynamics are very different than they were eight years ago, in the wake of the Rodney King riots. In 1993, police misconduct was at the top of the list of issues for black voters. Now, the city has a black police chief, Bernard Parks. While several candidates are calling for Parks' ouster, in the wake of the Rampart scandal and other abuses, Hahn, the candidate most ardently courting the black vote, is the chief's staunchest defender.

There have also been significant increases in both Latino and Democratic voter registration, and organized labor has reemerged as a potent political force in the city. Indeed, this race is at least partly a referendum on the power of labor, and whether it truly has come back from the collapse of the city's Democratic Party-labor coalition in 1993, which led to Riordan's victory over former City Councilman Michael Woo.

Labor wants the election to be a referendum on its resurgence in L.A. A reinvigorated, politically savvy labor movement has been given partial credit for a number of recent Democratic victories in Los Angeles, including Rep. Adam Schiff's victory over incumbent Jim Rogan last November. But some say labor's power in the city has been overblown. "They're extraordinarily powerful in the Latino areas of L.A.," said Republican political strategist Allan Hoffenblum, who is backing Soboroff. "I doubt if they had much to do with Adam Schiff. That district went 55 percent for Gore/Nader," he says. "Labor is powerful where the Latino vote is significant. Outside of that their power is money."

Certainly in the Rogan race, demographic shifts had at least as much to do with the former impeachment manager's defeat as did a push by big labor. And the unions suffered a humiliating defeat in a recent City Council race, when moderate Nick Pacheco defeated a labor-backed candidate in East Los Angeles in 1999, in an area which has been ground zero for the new labor push. So while labor has been willing to deliver hefty political contributions, precinct walkers and people to get out the vote on Election Day, this race stands as a true test of its political clout in Los Angeles.

Villaraigosa's close ties to labor have alienated many moderates in the Latino community. Pacheco has endorsed Becerra's mayoral bid, while centrist Democrat Alex Padilla is backing Hahn. So if Villaraigosa is truly trying to assemble a new "ethnic" coalition in Los Angeles like the old Tom Bradley coalition that dominated city politics for 20 years, he will have to reach wider than Bradley did.

The Bradley coalition was rooted in the civil rights movement of the '50s and '60s, made up of blacks and Westside liberals and Jews. During Bradley's four terms as mayor, he consistently polled more than 90 percent of African-American voters, who accounted for 25 percent of the city's voters. As black political power has receded, their percentage of the overall vote has fallen, down to 13 percent of the vote in 1997, and probably lower today. Latinos are expected to make up about 22 percent of all voters on April 10.

One of the central ironies in the race is that Villaraigosa probably wouldn't have a prayer if it weren't for federal welfare reform and former Republican Gov. Pete Wilson. Wilson's 1994 reelection bid featured a strong anti-immigrant subtext, coupled with his endorsement of Proposition 187. The backlash led to a massive naturalization and voter registration push among Latinos, which spiked upward again after President Clinton signed welfare reform legislation in 1996 that prohibited many legal immigrants from receiving social benefits.

Overwhelmingly, those new Latino voters registered as Democrats. Other groups including labor unions and the Southwest Voter Foundation have also targeted those new voters, registering thousands of new Democrats in Los Angeles over the last six years, Ludlow said.

But as a group, Latinos have proven they are not as likely to vote for one of their own as blacks. When asked about the electoral equation that would carry Villaraigosa to the mayor's office, Ludlow sketched out the targets in a hypothetical matchup with Hahn, and said Villaraigosa could not rely on the kind of support within the Latino community that Bradley received from blacks. "It's going to take 70 percent of the Latino vote, 20-25 percent of the black vote, and 40 percent of everything else," Ludlow said.

Ultimately, Villaraigosa's political fate may depend on Xavier Becerra. The six-term congressman is currently running strongly in the Latino community with 30 percent of the vote, compared to Hahn and Villaraigosa's 19 percent, according to the most recent L.A. Times poll. Most think that the bulk of the Becerra vote would go to Villaraigosa in a runoff, and vice-versa. That led some of the city's Latino leaders, including County Supervisor Gloria Molina, to try to broker a deal where either Villaraigosa or Becerra would step aside. Former HUD Secretary Henry Cisneros reportedly also brokered such a meeting. One scenario had Villaraigosa dropping out of the race. In return, Becerra would give up his congressional seat for Villaraigosa next year. But Becerra wouldn't bite.

"I'm not interested in cutting some backroom deal," he says.

Becerra is something of a wonk. Knowledgeable and approachable, he has been depicted by the local media as a "Boy Scout." His campaign stands in contrast to the bad-boy edge of Villaraigosa's, but it also lacks the dynamism. On a hazy, muggy Sunday afternoon, hundreds of people are gathered at Ritchie Valens Recreation Center in Pacoima. Most are inside the rec center celebrating the late, local rocker's induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but about 30 people have gathered outside to hear Becerra speak.

This is one of more than 60 gatherings that Becerra calls "neighborhood meetings" he has held across the city, reinforcing his campaign theme to put "neighborhoods first."

Becerra suffered a major setback last week when Molina, a longtime political ally of Becerra's, came out in support of Villaraigosa. "What [Villaraigosa] has been able to put together speaks mightily about his ability to bring this city together," Molina told the L.A. Times.

As Villaraigosa picks up steam, Becerra's support seems to be lagging. But Becerra warns he should not be written off. "I've been underestimated before, and I've always surprised people," he says, pointing to his undefeated record in elections.

Villaraigosa is mostly acting as if this is a two-man race between him and Hahn. But a Hahn-Villaraigosa runoff is far from a done deal. Even though labor plans to spend up to $1 million for Villaraigosa, and the Democratic Party plans to chip in anywhere from $500,000 to $1 million, the race remains extremely fluid. In this city of more than 3 million people, political strategists estimate it will take only 125,000 votes to get into the runoff, so variables like turnout become key factors in determining a winner. "The higher the turnout is, the better it is for Antonio," Ludlow says.

So for now, Hahn can still largely afford to be a political cipher. With his strong roots in the city's black community, he is well positioned as the default candidate, for a variety of voters, depending on who joins him in the June runoff. In a Hahn-Villaraigosa race, Hahn becomes the de facto conservative, bringing a unique coalition of blacks and Republicans behind him. If it is Hahn-Soboroff, Hahn becomes the lefty running against a self-financed Republican businessman.

In its dual endorsement of Hahn and Villaraigosa, the Times questioned Hahn's "fire in the belly," and privately his opponents also raise questions about his desire to be mayor. But in the Bush era, being the nonchalant son of political legacy may not be such a bad thing.

On a Saturday morning, the gray-haired city attorney pops into his Crenshaw Boulevard office to meet with a small handful of supporters before walking precincts. His pep talk is sufficient, even if it's not the "I Have a Dream" speech. Above all, Hahn just seems like a nice guy.

After a quick talk about "the people's campaign" and "making this town work," Hahn tells his precinct walkers to "be nice to everybody."

Today, Hahn is going door-to-door in Lemeirt Park, a bastion of Los Angeles' black middle class. This neighborhood is not what people normally think of when you mention South Central Los Angeles. The streets here are as wide as they are in Beverly Hills. The front lawns look like putting greens, and Range Rovers and BMWs sit in the long driveways.

This is Hahn's base, and he owes much of that to his father. This becomes apparent as Hahn goes from house to house. "I knew your father. He was a great man," says one woman. "And you look as nice in person as you do on TV."

Hahn speaks competently about the issues he says are the most pressing: education, affordable housing, traffic, the LAPD. But there are times when he shows a real distaste for the tone of political campaigning. When asked about his front-runner status, and the bull's-eye on his back that has come with it, Hahn just smiles and shakes his head.

"You know, I wish those polls had never come out," he says. "Everyone was real nice to me before that." But with the race entering its final days, and at least one spot in the runoff up for grabs, the attacks on Hahn and his record have begun. Soboroff, for instance, has taken swipes at Hahn for playing front-runner hide-and-go-seek by ducking candidate forums.

But there is little evidence that those attacks will stick. In a race with so many candidates, with such similar stands on most of the major issues, it is proving difficult for candidates to break out of the pack.

One of those candidates trying to break out is Steve Soboroff. In many ways, he is running as a Riordan clone. Though he has served as L.A. parks commissioner, he has never held elected office, he's poured more than $250,000 of his own money into his campaign, and he is Republican. By most accounts, he's running third, but he needs to siphon support from a crowded field of also-rans to have any hope of making it into the runoff.

At a recent candidates' forum in West Hills, an affluent suburb in the northern San Fernando Valley, about 50 people trickle into Shomrei Torah Synagogue to hear from the folks who would be mayor, but only Wachs and Soboroff, both Jews, show up.

Soboroff is working the room. A small army of his campaign workers set up tables with Soboroff literature underneath signs for the temple's upcoming "Reggae Passover." He's in full campaign mode. He's donned a white satin yarmulke, his own, and is aggressively shaking hands and talking to anyone who will listen. "He seems businesslike, like Riordan," says Ari Lappin, a resident of nearby Woodland Hills. "That's good."

But former Riordan political strategist Steinberg warns that Soboroff may have difficulty replicating Riordan's 1993 victory.

"For one thing, in 1993, GOP registration was just under 26 percent in the city. It's now under 21 percent," says Steinberg. "In a race that may be decided by a few thousand votes, that 4 point shift is very significant."

And many of Riordan's backers have defected from Soboroff. Riordan, they say, was the right candidate at the right time for Los Angeles, but now the city must move on. As early as October 1998, Bill Wardlaw, a key Riordan financial donor and one of the most powerful men in Riordan's City Hall, said, "The next mayor will not be a Republican businessman." Wardlaw has since thrown his support behind Hahn. Other parts of Riordan's financial team, including billionaires Eli Broad and Univision owner Jerrold Perenchio, are backing Villaraigosa.

Steinberg also says Soboroff has run a lackluster campaign thus far. "Soboroff's principal challenge is that he has not coalesced a Republican base, which is absolutely essential to get into the runoff," he said. "He did not make a significant effort to crystallize the base. He acted as if it was secure, and it's not. The California Republican Party has been conducting an effort to salvage that failure. Whether or not they can still be successful is still problematic."

And Soboroff has to contend with Joel Wachs to get that vote. Though Wachs is unlikely to make the June runoff, he is, as of now, Soboroff's main competitor. Kathleen Connell is also running on a platform of fiscal conservatism, and may be drawing votes from both Wachs and Soboroff.

Wachs, who has represented the valley for 30 years on the City Council, is difficult to pin down politically. He has been a major booster for arts in the city, but made his reputation as a fiscal conservative. As the only openly gay candidate in the race, he has also assembled the most interesting coalition: His campaign consultant is Sue Burnside, a well-known gay political operative, while his media campaign is being run by Don Sipple, a Republican consultant who counts George W. Bush and John Ashcroft among his former clients.

With Connell, Soboroff and Wachs all vying for essentially the same vote, the three fiscal conservatives may well end up keeping each other out of the June runoff. The race is still very much up for grabs. "I think it's very fluid," said political strategist Allan Hoffenblum, who is supporting Soboroff. "The TV commercials are hitting heavily now on L.A. television. It's going to boil down to what it always does -- the candidate that does the best job in identifying their most likely supporters and motivating them on Election Day will get in the runoff."

With Hahn a fairly sure bet to make the runoff, the question becomes whether one of the conservatives can break out of a crowded field, or Villaraigosa can build a coalition wide enough to propel him into Round 2.

Some say in this era of secession talk and increasing local control, Villaraigosa's throwback message may simply be out of date. "It is frequently said that L.A. needs an old-fashioned leader to build coalitions across the city, someone who can unite the disparate parts of Los Angeles and resurrect a shared sense of cityhood," Gregory Rodriguez wrote in a Feb. 18 Los Angeles Times article that, in some quarters, was read as a slap at Villaraigosa. "But L.A. is not greater than the sum of its parts. The disjuncture between one end of the city and the other is part of its greatness. Migrants may move to New York to become part of a civic enterprise, but the beauty of L.A. is that here one doesn't feel obliged to be a part of anything."

Villaraigosa's backers are hoping that his disparate coalition will add up to more than the sum of its parts and that the city wants to recreate a new version of the coalition that elected Tom Bradley. That coalition helped L.A. gain a civic sense of itself as a community that had transcended race by facing it.

"We're putting together an energy with this campaign that's second to none," Villaraigosa says. "This city is ready."

Shares