You'd figure that any confirmation hearing that begins with Sen. John Warner, R-Va., walking in wearing a kilt -- in honor of the 681st anniversary of Scotland's declaration of independence -- would be interesting. You'd be wrong.

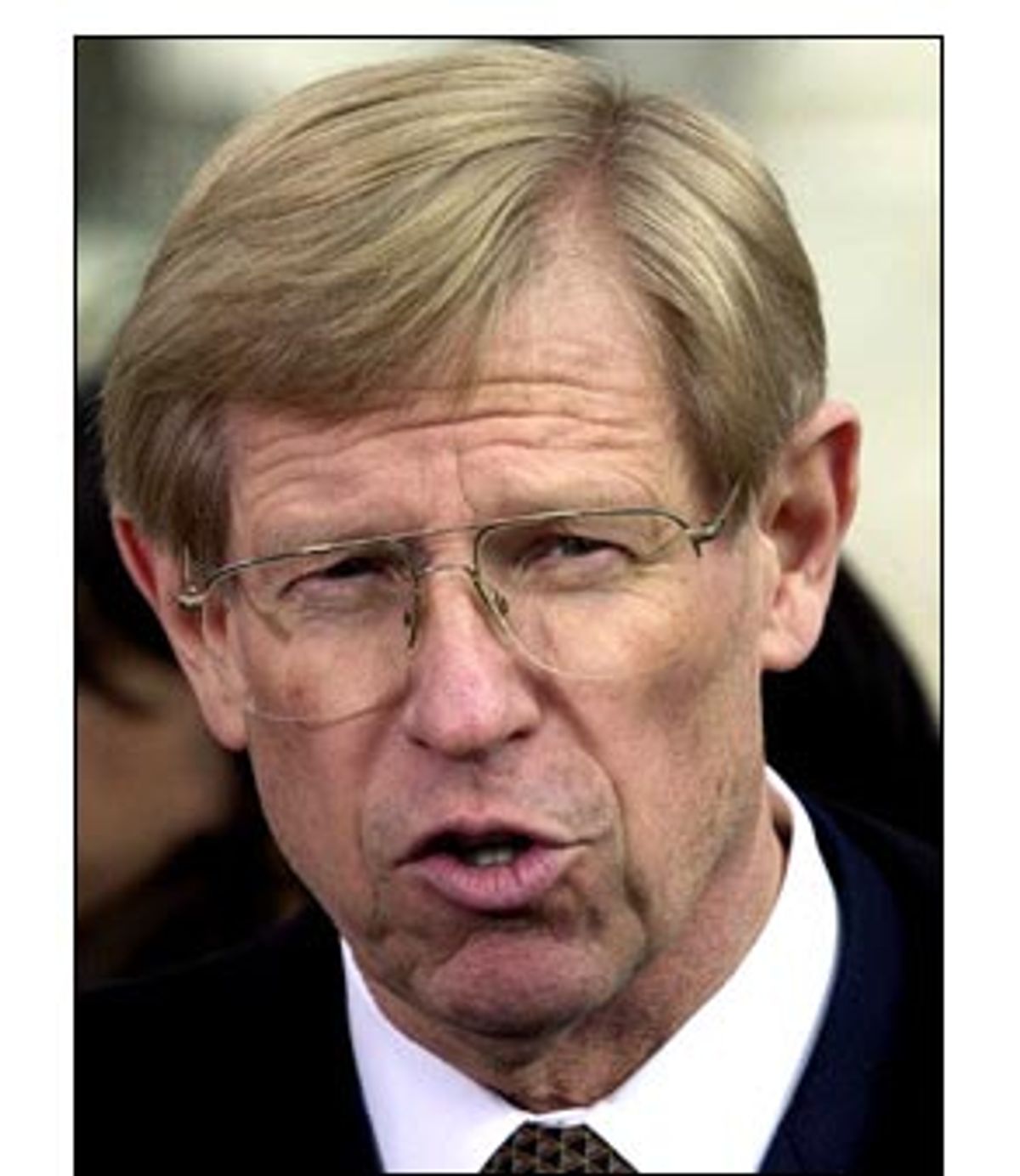

The confirmation hearing for Solicitor General-designate and noted Clinton hater Theodore Olson was a tedious affair, with Democratic senators repeatedly sniping with Senate Judiciary Committee chairman Orrin Hatch but barely landing a glove on Olson. As solicitor general, Olson would have considerable discretion in choosing which cases the administration pursues in the Supreme Court, and would be likely to argue many of the most highly charged cases himself. Consequently, Democrats have deep concerns about putting a stalwart Republican partisan in that job. And there's plenty of partisan raw meat in Olson's past.

Most recently, Olson was the lawyer for then candidate George W. Bush in Bush vs. Gore, the Supreme Court case that stopped the Florida recount. He has also sat on the board of the conservative journal the American Spectator, and has written several articles for that publication, shredding former President Clinton, the former first lady and their associates for everything from gross incompetence to serious crimes.

Perhaps the most serious skeleton in Olson's closet, though, is his alleged role in the "Arkansas Project," the pay-for-dirt investigation funded by arch-Clinton foe Richard Mellon Scaife. In 1993, Scaife reportedly began funneling $1.8 million to the Spectator in exchange for a steady supply of anti-Clinton investigations and exposés.

Olson asserted Thursday that he had been only peripherally involved in Scaife's venture, testifying that he participated in the project "only as a member of the board of the American Spectator." Olson also denied ever hosting a meeting of the project's principal pursuers. However, according to the research of Salon columnist Joe Conason, a 1993 meeting of the Arkansas Project took place at the Washington offices of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, where Olson is a managing partner. An audit of the Arkansas Project's books in 1995 also showed more than $14,000 in payments to the firm from March to August 1994.

The first of those payments came just a few weeks after one of Olson's most scathing anti-Clinton pieces in the Spectator. In "Criminal Laws Implicated by the Clinton Scandals: A Partial List," which appeared in February 1994, Olson provided a "fairly impressive catalogue of possible crimes" that Clinton, his wife and others could be charged with. According to the piece, even before Monica Lewinsky and the Chinese fundraising scandal, Clinton could have faced 178 years in jail and more than $2.5 million in fines.

That's quite a heavy sentence, and one that Olson had originally not wanted to take credit for. The piece was credited to "Solitary, Poor, Nasty, Brutish & Short," a pseudonym for the Spectator's phony legal team, though Olson retained the copyright to the piece. In Thursday's hearing, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., criticized Olson for his undercover screed and for another piece, "The Most Political Justice Department Ever: A Survey," published just last September and aimed at former Attorney General Janet Reno. In that article -- to which Olson did attach his name -- he blasts Reno for being in the pocket of the Clintons.

There is ample evidence that cannot be ignored that, from the beginning, Janet Reno allowed her department to be overwhelmed by partisan politics and that she readily submitted to the personal and private interests of President Clinton and his partner in running the department, First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton. Space permits only a limited review, but what follows is a partial evaluation of Janet Reno's tenure according to commonly accepted standards for measuring the work of her department.

Feinstein said she had been leaning in favor of Olson's nomination until she read his work. "You identify yourself pretty clearly as a very strong political partisan, not as someone who is reserved, temperate and evenhanded," she said.

But in his testimony, Olson was the model of temperance. Rather than accept Feinstein's estimation that his work was "somewhat harsh and biting," Olson preferred to characterize his articles as "hard-hitting." He also noted that he was merely the coauthor of the 1994 piece, and then dissembled about his intent. That article "talked about potential -- not necessarily, not crimes that had been committed, but the potential crimes that could arguably have been implicated by the conduct that had been reported," he said.

Olson put on the soft-focus lens when discussing another chapter in his anti-Clinton crusade, his representation of Whitewater witness David Hale, which began in 1993. Hale, formerly a judge in Little Rock, Ark., had claimed that then Gov. Clinton had pressured him into making an illegal $300,000 payment to Clinton's partners in the Whitewater land deal. When Hale was called to testify before Congress, Olson represented him.

Though ranking minority member Sen. Patrick Leahy of Vermont asked whether that action proved that Olson was an irreversible partisan, Olson characterized his relationship with Hale as almost an act of charity. "Mr. Hale agreed to pay our fees," Olson said, denying that his firm was reimbursed for its work by Scaife. "As it turns out, he was not able to pay his legal fees." Olson went on to say that he had never been paid for that work, and jokingly invited anyone in the hearing room to ante up on Hale's behalf.

When Leahy finally started asking questions about Olson's role in the Arkansas Project, it was after 4 p.m. and the hearing room was nearly empty. Most of the audience and reporters had long since left. That, according to a source close to the Democrats on the panel, was part of a Republican plan to slip Olson into his solicitor general post with the minimum of attention.

During the hearing, several Democrats noted with irritation that the confirmation hearing had been scheduled for the same day that the Bush budget plan was being debated on the floor, and just a few working hours before the body would be recessing for the spring holidays. Furthermore, Olson shared his confirmation hearing with Larry Thompson, an affable Georgia attorney whom Bush picked for deputy attorney general, further diminishing the time available to pick at Olson's record. Even the location, at the end of a rat-maze walk in the Senate building's basement, seemed designed to discourage the attention of the press and the public.

That list of grievances, along with the general perception that Republicans won't play nice on judicial nominations, put Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., in a particularly foul mood. Ostensibly questioning Thompson on the need for bipartisan cooperation in judicial matters, Schumer said that the administration's efforts so far have fallen short of his expectations. "I have to tell you, we've been off to an inauspicious start in this regard," he said. "But I can tell you, speaking only for myself, I'm not going to be rolled over on this."

The Democrats have one final hope: Olson has been asked to respond to written questions from both sides by the end of the spring recess on April 22. This final procedural move will allow Democrats to probe deeper into Olson's Scaife-associated past, according to one Democratic Senate source. Yet at this point, it appears a major controversy would be required to derail Olson's nomination. Even liberal champion Sen. Ted Kennedy, D-Mass., said he planned to vote in favor of Olson. Hatch is pushing for a final decision by April 26.

Shares