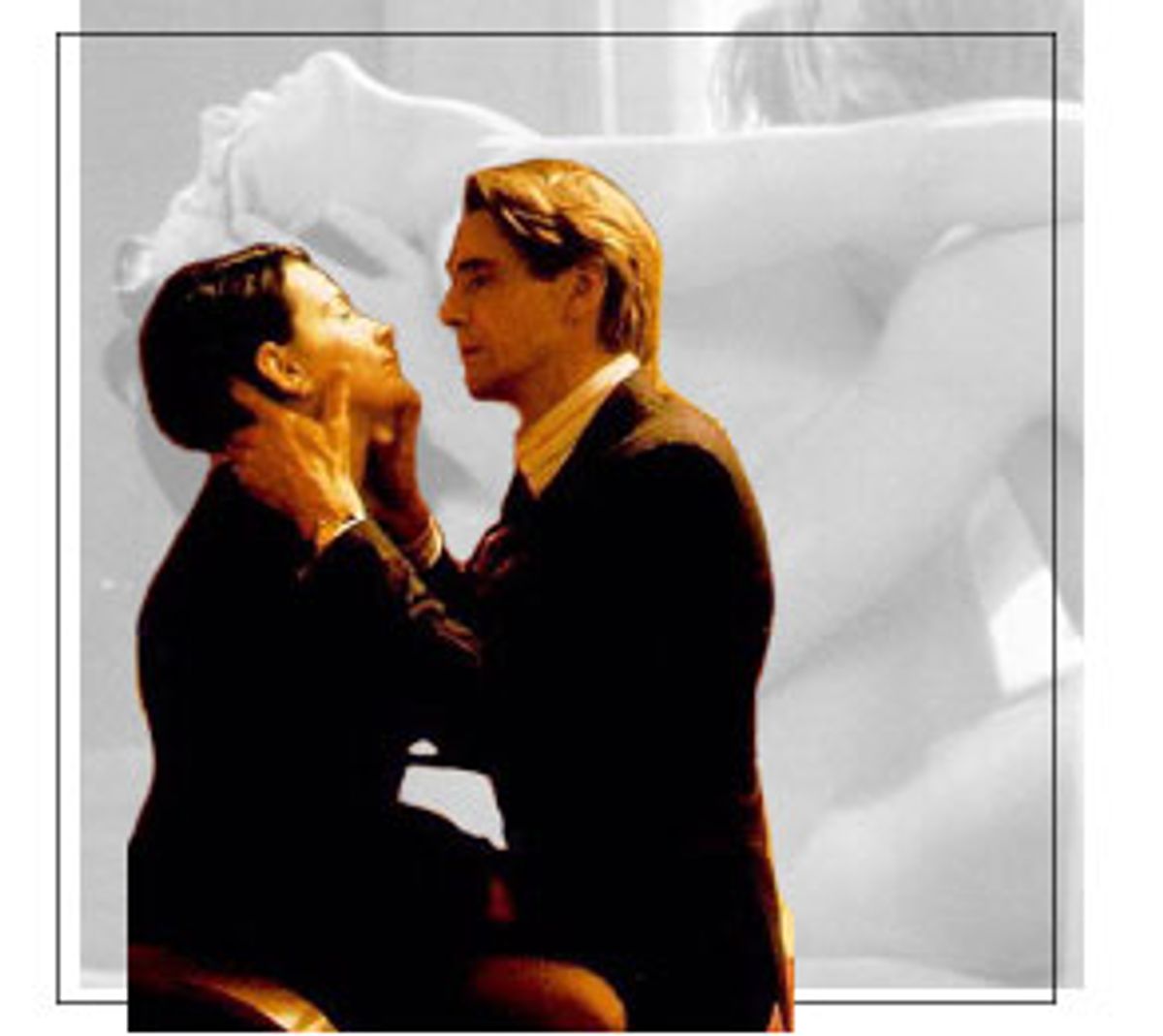

I saw "Damage" again the other day, the 1992 film by Louis Malle, adapted by David Hare from the Josephine Hart novel. It's the one where Jeremy Irons plays a government minister in Britain. His son takes up with a young woman, played by Juliette Binoche -- except that Irons and Binoche then begin an intense sexual affair. When it is discovered, the son dies as a result of his horror. The minister is ruined.

I don't much like the film (apart from Miranda Richardson's performance as Irons' wife). Malle's chilliness isn't kind to the depravity of the subject. But I saw it with fresh eyes now because I'd just been reading the memoir of an Englishwoman named Christine Keeler. Does anyone outside Britain or the '60s remember her? She was a call girl who had an affair with a government minister named John Profumo, somewhere around 1962. She was also involved with a Soviet officer at the Russian Embassy, so there was the sniff of espionage. Profumo lied about the relationship to the House of Commons, and then he was found out and had to resign. The Macmillan government fell, in no small part because of this. And Keeler passed on into ordinary life.

In 1989 a film was made about it all, called "Scandal," with Joanne Whalley-Kilmer as Keeler and Ian McKellen as Profumo.

Anyway, in "Damage," Anna (the Binoche part) phones Irons at his ministerial office. A secretary fields the call and smells a rat immediately. But Irons writes down her address and says he'll be there in an hour. He's an up-and-coming man in the government, a highflier, and as handsome and grave as Irons: prime minister material. On the spot, in the middle of the day, he decides to get up and leave his desk, his routine and his schedule to go and see this wan-faced, dark-minded woman as beautiful as Binoche. She is fatal, but empty. It's a film in which Binoche hardly ever smiles (except as a lie).

Having just read about Profumo's fate, the scene meant more. I felt the brief hesitation between order, good sense, purposeful capitalist accumulation of time to advance oneself, of doing the right thing -- or, if not right, the proper thing -- between that and madness, violence against order and propriety, the moment of absurd fateful courage that will do so much damage.

Irons is so much in both worlds still that he has his chauffeur-driven ministerial limousine take him to the assignation. And he walks down the narrow, cobbled mews where Anna waits like the most glaringly elegant suspect. When he enters her flat, there is no talk, no fuss with explanation or justification. She leans against the bed in a white blouse and a black skirt, and then slides to the floor. He leaps upon her like a wolf. You can feel that a man might give up everything -- the world, its history and culture, life on the planet as we know it -- for such a moment. And it's terrible and frightening, but there's still no talk, just the tiny noises they utter in lovemaking.

Not that there is ever anything as warm as comfort or affection between them. Anna is a monster of loneliness and hunger. She is not civilized. She will take this minister down with her along with the life of his family and the idea of stability and trust. The scene makes such appalling risk credible and human. It makes you fearful of going out, lest you might meet such dangerous new people as Anna.

Shares