Entering the wood-paneled hall, it's tempting to check the surrounding faces for telltale signs: mushy black eyes, hospital-shaven heads, the acknowledging smirk on a bruised face. In advance of "Postcards From the Future," the first-ever Chuck Palahniuk conference, no one seems quite certain who will show up in the sleepy northwestern Pennsylvania town of Edinboro, nor what form their dedication to the cult-favorite author of "Fight Club" might take.

"It's kinda weird," says Amy Dalton, coauthor of the Chuck Palahniuk.net Web site, one of the conference's sponsors, "because I'm a little bit afraid of some of these people. I try to think that they're just like me, and they're interested in this writer. But there're people on this other [online] message board who are really 'fight clubbing' it -- not like the guys on our board saying 'Why isn't there a fight club in Omaha?' These people are really doing it!"

Christian McKinney, the 22-year-old Edinboro University senior who is the main organizer of the conference, was similarly anxious in the days leading up to the event. At some of Palahniuk's recent speaking engagements, McKinney explains, the author has been asked disconcerting questions: "People were asking him, basically, to tell them how they should live their lives. And when he refused to tell them, they started shouting at him."

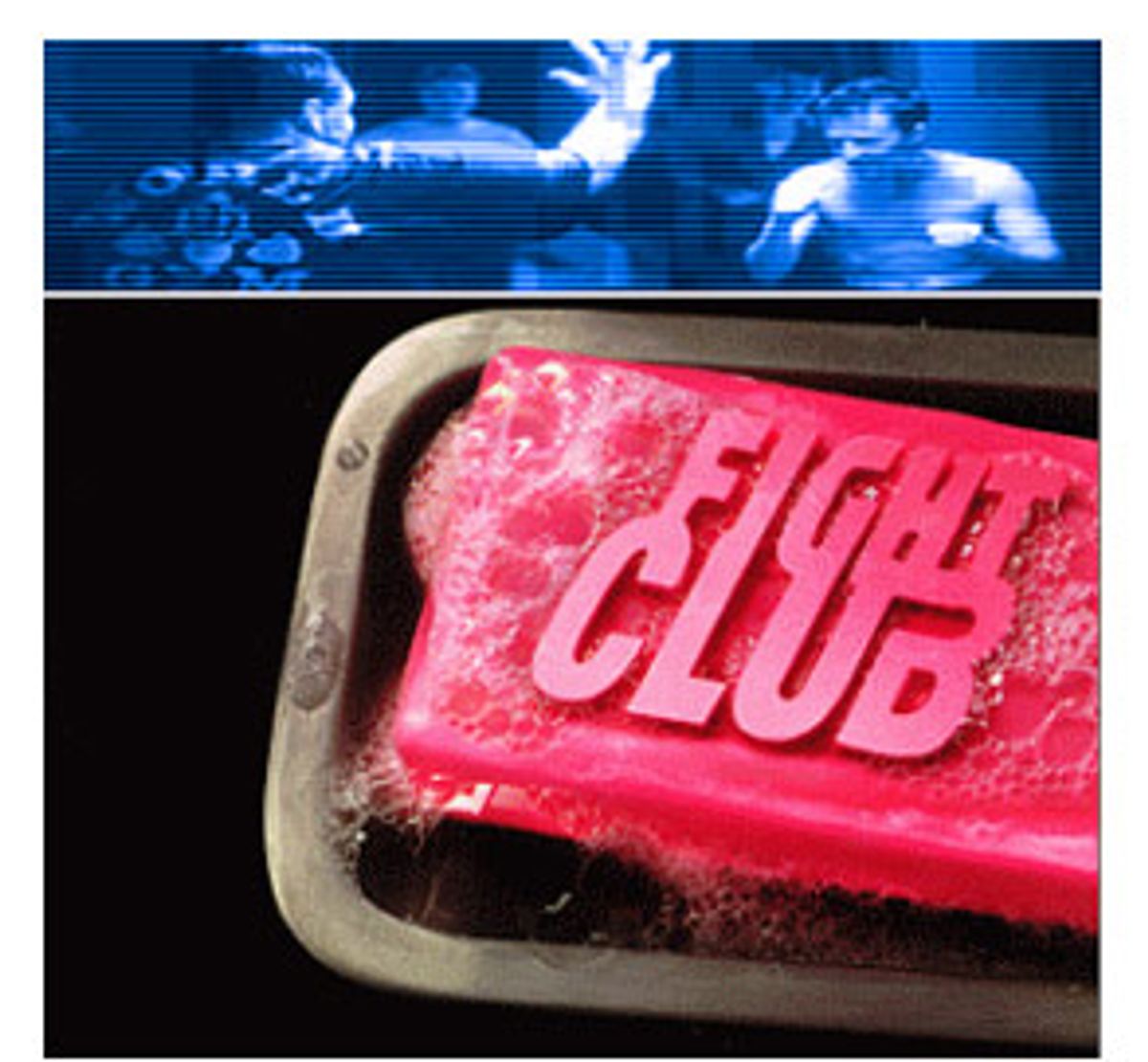

Palahniuk's three novels, "Fight Club," "Invisible Monsters" and "Survivor" (the fourth, "Choke," comes out next month), all hinge on issues of postmodern sexual identity, consumerism and fame, and they've struck a chord with fans of contemporary literature as well as the young, suburban outcasts who popularized Palahniuk faves like Marilyn Manson and Nine Inch Nails. With the cult success of David Fincher's 1999 film adaptation of "Fight Club" -- starring Brad Pitt, Ed Norton and Helena Bonham Carter as nihilistic characters who create an ominous underworld culture revolving around floating bare-knuckle fistfights -- the author's fame spiraled in both the ivory tower and on the streets. While teachers such as Edinboro University literature professor Janet Kinch were teaching Palahniuk in their courses, less scholarly fans were allegedly punching each other's lights out in real-life "fight clubs" across the country.

It's hard to know for sure, though, because, according to Palahniuk's novel, the first rule of fight club is: You don't talk about fight club. With the beginning of the Palahniuk conference on April 6, however, any anxiety about potential violence has faded. Edinboro's University Center multipurpose room is filled with well over 100 of the 165 Palahniuk enthusiasts who signed up for the event, and it's apparent that the "fight-clubbers" failed to make the journey. Most of the men in attendance, like the yuppie narrator at the beginning of "Fight Club," look like they haven't been in a fight since the schoolyard bully called their mother a bitch in the hall after science class. Apparently, such topics as "The Quest for Fulfillment: An Analysis of Recurring Themes and Character Motivation in the Works of Chuck Palahniuk" and "Reality Isn't What It Used to Be: Postmodernism and 'Fight Club'" appealed more to the bookworms than the basement brawlers.

Still, the audience watching the screening of Fincher's film, which was interrupted by a Q&A session with Palahniuk himself, is a mixed bag of 21st century types. Among the attendees, mostly in their 20s, are obvious devotees of the self-destructive heroine of "Fight Club," Marla Singer -- goth girls in faded prom dresses, black boots or pink hair. One Marla, clad in leather, eyes blackened by mascara rather than barroom blows, is taping every word the auto mechanic-turned-author says. "You have to see my microphones," she says to another fan with a digital recorder. "They cost a thousand dollars."

Obsessive documentation seems to be the order of the day -- there are at least four video cameras, numerous digital audio recorders and all manner of photo amateurs, uploaders and cellphone junkies. The crew from Chuck Palahniuk.net is even filming a documentary. Beside the Marlas sit the emulators of Tyler Durden, the gleefully violent antihero of "Fight Club": college boys with pompadours or goatees, uniformly clad in brown leather jackets.

Sitting in front of me are two Tylers whom I recognize from the check-in line at the appropriately run-down and ant-infested Edinboro Ramada Inn. During the screening, I can hear them whispering along with Tyler as he states his masculinist philosophy. "We're a generation of men raised by women," they both mouth, and I get the impression they might break out in high-fives at any moment. "I'm not sure another woman is what we need."

But mixed in with the Tylers and Marlas are people who look more like graduate students, as well as writers and literature buffs who've driven and flown from as far away as Arizona, Oklahoma, Michigan and Long Island, N.Y., to take part in a 48-hour celebration and discussion of an author whose work, many of them feel, will one day take its place on the classics shelf.

"I see ['Fight Club'] as a cultural marker for the 1990s and this decade," says Kinch, whose appreciation of Palahniuk's fiction was an impetus for the conference. "The conflicts it brings up -- we're not talking about outcasts of society, trying to see how they can fit into society. We're seeing mainstream 'normal' folks, who look normal, and have normal jobs, being so desperately unhappy. They're living lives not only of quiet desperation -- they're not even living! And I think that's how 'Fight Club' really resonates with all of us."

"This work is ... very entertaining -- a lot of people from our age group really relate to this material, and to this kind of humor," says McKinney. "Plus, it's very fresh -- this isn't an author who's been dead for 100 years, this is an opportunity to discuss this work for the first time and not rely on criticism that's been handed down like dogma."

Some of the weekend's presentations seem only tangentially connected to Palahniuk and his work. "The big lesson of stage combat," says a theater student demonstrating some techniques, "is that groin kicks are very, very popular." Then there's the roundtable discussion on coping mechanisms ("Because I Can't Hit Bottom, I Can't Be Saved"), the interpretive dance series performed by a group of Mercyhurst College students and several other "creative works." The performances aren't as off-base though, as they might at first seem. Many conference-goers like Palahniuk's fiction because he excels at depicting characters who are drawn from the auditorium of consumer culture and into real life.

"The major device [in each novel] is the secondary character who catalyzes growth and enlightens the narrator," states Scott Heckmann of UCLA in his paper "Chuck Palahniuk's Fiction." "Palahniuk's [work] influences the reader the same way his secondary characters influence the main character. Palahniuk is Tyler Durden, Brandy Alexander [from "Invisible Monsters"] and Fertility Hollis [from "Survivor"]; he is the character that finds a hero in a spectator. By causing the reader to become the central character, in the end, the reader is also heroic."

In his presentation on "Fight Club: Beating Men Out of Submission," Bowling Green State University graduate student Rafael Colon Gonzalez agrees: "Tyler Durden's role in creating fight club is to save these men who are controlled by capitalism. The violence that Tyler wants men to take hold of is normally only fed to them as spectators."

One presenter, Edinboro student Mike Oelke, went so far as to say that the reining in of their violent instincts and the relegation of men to the spectator stands is the root of many men's inability to cope with society. In "Human Services and Their Failure as a Therapeutic Tool for Men," Oelke says that "what makes men feel good about themselves is being able to look in the mirror and see a man they can respect -- not a coward, not a slave, not a charlatan. This can only be achieved by the building of character. From a young age, little boys are taught that when they have a problem ... they settle it 'like men.' So they fight. This rite of passage has been taken away from today's man, and we're all suffering for it."

At the Boro Bar, Edinboro's most tolerable watering hole, a motley crew of Chuck-heads gathers. Across the table from me, James Dolph talks about his own conference presentation, "Chuck Palahniuk's Virulent Burroughsian Visions." A student of the beat school, Dolph savors Palahniuk's paranoia. But I also recall that during one of the Q&A sessions with Palahniuk he proposed that "Invisible Monsters" was, perhaps, an homage of sorts to C.S. Lewis' "'Til We Have Faces." (Palahniuk said he hadn't read Lewis' reworking of the Cupid and Psyche myth.)

Dolph studies full time as a graduate student in literature at the University of Central Oklahoma, and then works 40-hour/three-day weekends as a nurse at the Oklahoma City Jail. His eyes are chronically shadowed from lack of sleep. He thinks a lot about literature and how it relates to the harsh environment that surrounds him.

"You know Terry Nichols, McVeigh's accomplice in the Oklahoma City bombing?" asks Dolph with an Okie drawl, explaining why he hates his job. "I see him every day at work. The worst part of it is that he's so nice. These murderers are always so nice! It makes you long for the Mansons, guys you could instantly recognize as what they are.

"Sometimes," Dolph continues, raging against the hardcore criminals he's grown to despise, "I put a sign up behind my desk that says [quoting "Fight Club"] -- 'You are not a beautiful and unique snowflake.' But they don't even get it."

What does the author himself think of this kaleidoscope of responses to his work? "It's incredibly exciting," says Palahniuk. "Not so much that they're dealing with the books themselves, but that they're dealing with the issues raised in the books. It's an exploration of these issues, not just a big Chuck love- or hate-fest. Now people are looking at these issues, and it's like a continuation of what the books were supposed to create."

Wherever Palahniuk goes during the conference, a long line of attendees seeking his attention forms. They want the longhaired, casually dressed anti-guru to weigh in on their theories about his novels, or to autograph a paperback, or simply to shake their hands.

The conference may have escaped the fight clubbing that some feared, but there is a certain degree of geekishness that can't be ignored: An obsessive fan corrects Palahniuk on the finer points of which screenwriter added which lines to the Fincher film, and during his wrap-up Q&A on Saturday afternoon, the author deftly parries the question "Given the choice, would you rather be a robot or a vampire?" And, like all good cult phenomena, Palahniuk's writing inspires his readers to construct their own version of the story by imagining what happens to his characters off the page.

There is, however, a more immediate reason that Palahniuk's work resonates with the grad students and barflies who have made the migration to Edinboro.

"It's the way we all want to write," explains Dennis Widmyer of Chuck Palahniuk.net. "He has a style that's so simple and to the point, and yet no one writes in that way -- it's written from the gut. He writes about things that we're all thinking, but we don't say. His stuff has all been done before, but his books are kind of antiestablishment."

When I meet up again with Christian McKinney, he looks like he hasn't slept in days -- to him, at this point, everything seems like "a copy of a copy of a copy," as the narrator in "Fight Club" assesses insomnia. For the past week, McKinney has devoted his every moment to working out conference details. The project began over a year ago, when Kinch asked McKinney to come up with a name, someone he'd like to bring in as a guest speaker for the university honors program. When McKinney brought her the name Chuck Palahniuk, he thought she wouldn't have heard of him or his books.

"I got the biggest grin on my face," says Kinch. "I just wanted to say, well, maybe I'm not quite as out of touch as you think! When he said that he'd really like to have [Palahniuk] as a guest speaker, I said no, we're going to hold a conference."

Palahniuk took a bit of persuading.

"I had three books out at that point," says Palahniuk. "I was questioning whether or not I really had anything to offer. It just doesn't seem much of a body of work to hold a conference on. But Janet and Christian were so insistent -- how could I say no to that kind of request?

For a small college like Edinboro, celebrating an unconventional young writer with a cult following turned out to be an inspired choice. "Edinboro is not really known as a terribly academic center," says Kinch, "and for us to be able to do something that's cutting edge -- it gives us some notoriety. But more importantly, the fact that our students will get something out of this, it's not just a media event, it's not just a blip on the TV."

Speaking to the entire conference, the irreverent young author at the center of it all gets decidedly caught up in the enthusiasm.

"If I read a book, and it's incredibly well-written," Palahniuk says in his keynote address, "I read it quickly as much out of enjoyment as out of the fact that it makes me want to write. Creation that generates creation is the highest tribute. I would say that there is going to be work coming out of this room that vastly dwarfs my work, and that is the greatest tribute ... that could ever be given to me." After his speech, Palahniuk adds privately, "If I can be part of a catalyst to creating a generation that revolutionizes its culture, my God -- I can't think of anything I'd rather do! I seriously want my books to be forgotten [due to] the mass of extraordinary work that these people create."

Shares