Photographer Helmut Newton is what Vogue and Vanity Fair regard as a naughty boy. But grown-ups don't have to scare so easily. The editors of those magazines congratulate themselves on the cutting-edge autopsies he brings to their pages. They say, "Isn't he perverse, depraved and shocking?" But in the delusions of glee they fail to notice little Newton's monotonous enthusiasm for death, for some trick or slick of the light that can make a living human corpselike. Perhaps they also miss what could be their own memorials, done in a blancmange marble one might mistake for flesh.

The publication of "Helmut Newton Work," an albumlike book with a chronology of all the exhibits Newton has had, is ostensibly the celebration of a great artist at 80. (Newton was born in 1920, in Berlin, and this book was made to coincide with a major show at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin from November 2000 to January 2001.) But what sort of artist is one to have been so dependent on the fashion industry for work and who, by his own admission, prefers to do portraits of the "infamous" -- movie stars, politicians, the rich and the scandalous -- in short, those who find a certain glamour in being photographed by Newton, as if it paid for their place in the modern gallery of celebrity guilt.

But those who have their portraits done should train themselves in the way he treats his fashion models. He is not looking for lives or faces so much as attitude, the kind of sensuality poised on the edge of disease, a lean, meatlike nudity in which beauties seem ready to hang on the butcher's hook -- illustrious corpses, tender joints. The celebrities should pay attention to one of Newton's favorite ploys, that of putting warm bodies with plaster or porcelain simulacra. He uses mannequins, dummies, whatever you want to call them -- they are the perfect bodies that come in sections and that sell clothes in those very public forms of prison, the bright store windows.

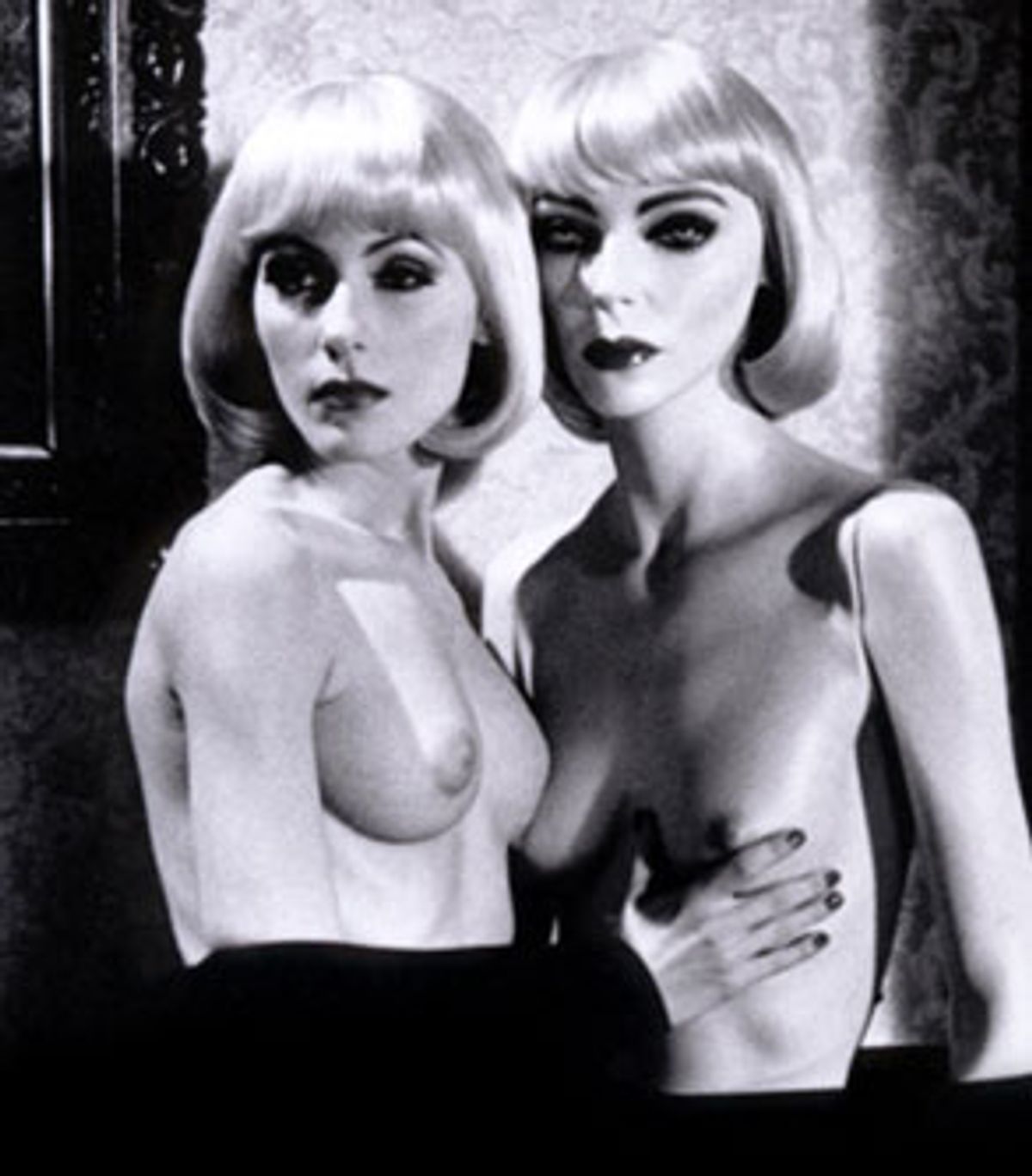

There are some haunting images in that vein, quite arresting if you're a connoisseur of all our contemporary forms of death. There's the blond, naked above the waist, turned to look over the camera's left shoulder, her hand reaching back to caress the breast of her twin, a blond mannequin -- except that the twin's breast is finer, more exactly conical, the nipple harder. The living woman's breast is not bad, but pessimists might detect those telltale warnings of sag (or gravity), that extra lining of flesh in the lower curve, the fall of Eve. It is also left to us to appreciate the implicit insult to the living woman, that she is nearly but not entirely dead. The mannequin's eyes are fixed, glassy, eternal, whereas the woman's are still vaguely pained, as if she cannot fully forget the erosions caused by aging.

I like another thing about this picture -- the way the two figures have been jolted out of an embrace by the light, and are placed in a bourgeois room with fragments of an armoire and a forlorn "old master" on the wall. There is a vestige of the social critic still in Newton, and it burns wanly in this air of intrigue in the parents' fusty old house. But it could have been a great picture if Newton had had real danger in his eye, if the living woman had had the lurid wounds of some operation, a mastectomy perhaps. Newton is never brave enough for such ordinary outrages. He can mock beauty, but he is squeamish about real damage.

Still, I would rather have that picture, or some of the other mannequin shots, than all the flagrant, contemptuous views of tall, nude models, with their skin not just sleek or slippery but often oiled and varnished. Indeed, the only handles you could discover are the breasts, the blank faces and the shaggy clumps of pubic hair. These are heartless pictures, drab erotica, with an odd air of the concentration camp about them -- an Auschwitz for perfect bodies. Again, that is a subtext that Newton hints at without grasping. I doubt that Vogue or Vanity Fair would go that far.

But there is a color picture called "Dummy and Human III," done for Oui magazine in 1977, that is entrancingly beautiful. A living nude stands at the left of the frame, seen from knee height to just below breast level. Her body is bent back. One hand rests on her hip; the other clutches the black beaded cloche on a mannequin. That dummy is kneeling, her head lowered for cunnilingus. She is in shadow, but there is light enough to pick up her jewelry and the café au lait of her exposed left breast, like a cup just stirred. It is a very sensual, tender pose, and the composition is enhanced by a careful cropping that is not common in Newton's work. The deep green fabric backdrop is very tastefully allied to the skin tones. It is a photograph, yet it conjures up thoughts of Ingres or Caravaggio in that the orgiastic stillness verges on something religious. The fact that one face is unseen and the other is in shadow is the beginning of real art.

In the section on portraits, I like a Catherine Deneuve picture from 1976, in part because it too is cropped, just above the line of her eyes. But there's frankness in the picture, an air of the tramp fighting the lady in Deneuve. It might be more striking if one didn't feel that it was derived from the way films directed by Luis Buñuel ("Belle de Jour" and "Tristana") have seen Deneuve.

There's also a striking, very tough-looking Sigourney Weaver, in a dress so drenched her nipples are like starter buttons. It gets the guy in Weaver all right, and the pose -- holding a cigarette in a raised arm -- is very intriguing. But it doesn't get her matching vulnerability, and it's finally not as compelling as some of the best views of her in the "Alien" films.

Newton has had an odd life, and this book is not very helpful about explaining him. It implies that he is Jewish, but never actually states it. I'd like to know so much more about how he worked in Berlin until December 1938, and then went to Singapore for two years before ending up in Australia. Was he ever drawn to photograph those places? There's one picture of him from 1958, taken by his wife, June (she works as Alice Springs): It shows a melancholy, wolfish face, with a sad, tough con man's gaze. Then there's another, from 1987, in Monte Carlo (where they live) of Newton sitting in shorts and wearing fancy high-heeled shoes. Here the look is complacent, superior, sneering; it's not a kind or an interested face. And I'm bound to add that in the history of good photography many artists' faces are filled with the curiosity they feel about looking. Newton's look, in contrast, is mean-spirited and past surprise. The coroner feels he has seen it all.

Shares