Champions are all alike; every loser is a loser in his own way.

Here is Ralph Branca, the Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher who came out of the bullpen to give up the "Shot Heard 'Round the World," Bobby Thomson's home run that won the 1951 pennant for the New York Giants, who had been 13 and a half games behind the Dodgers in August, and down 4-2 going into the bottom of the ninth in the final playoff game.

He's prostrate on the stairs in the Dodgers' dressing room, face buried in his arms. Branca is 25 years old. He's won 76 big league games, including 13 that year and 21 in 1947. He would win four in each of the next three years, and then, except for a two-inning relief appearance in 1956, would be out of baseball.

Here is Ralph Terry, the New York Yankees pitcher who came out of the bullpen to give up a home run in the bottom of the ninth inning of Game 7 of the 1960 World Series to Bill Mazeroski of the Pittsburgh Pirates, the only home run ever to end a Series seventh game. He's on the Yankees' plane back to New York, knocking back drinks. "I was in a daze for a few weeks," he would say later. Terry is 24 years old. The next year he would win 16 games. The year after that, he would win 23, and then he would throw a four-hit shutout to win Game 7 of the World Series.

And here is Willie McCovey, who made the last out of that '62 Series. He had stepped to the plate against Terry in the ninth inning of Game 7 with his San Francisco Giants trailing the Yankees 1-0, but with runners on second and third and two outs. After hitting a long foul, he hit a screaming line drive right into the glove of second baseman Bobby Richardson. A few feet in any direction and it would have been a base hit to win the Series. McCovey is 24 years old. He would play another 18 years in the majors, belt 457 more home runs to go with the 64 he'd already hit, but he would never play in another World Series.

Now it's 1986 and McCovey has been voted into the Hall of Fame. He's walking through the San Francisco airport, on his way to catch a plane to New York for a press conference in Cooperstown. A reporter asks him how he'd like to be remembered. "Well," the big man says, "I'd like to be remembered as the guy who hit the line drive over Bobby Richardson's head."

In "Heartbreaker: Baseball's Most Agonizing Defeats" longtime Chicago baseball writer John Kuenster tells 15 such stories from the second half of the 20th century, some (Branca, Bill Buckner's error in the '86 Series) more agonizing than others (Cubs sort of fold down the stretch in '69). But he misses one. It should be Chapter 6, right before "1972: A Wild Pitch Sinks the Pirates." Or it could just replace that Cubs story as Chapter 5.

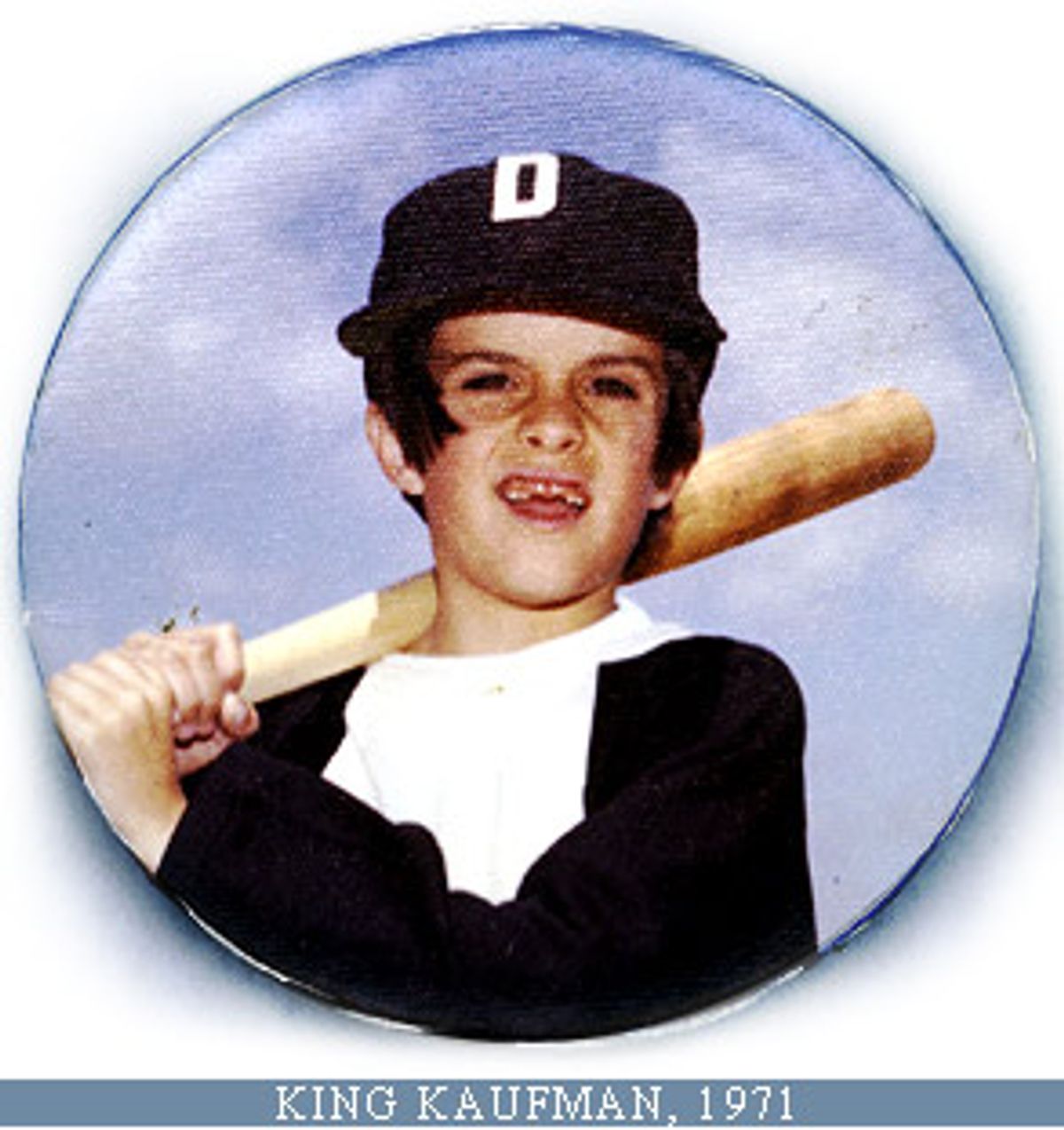

It would be titled "1971: The North Venice Little League Minor Dodgers Almost Win a Game."

North Venice Little League sits atop the Steepest Hill in the World, as you'd know if you ever tried to ride your bike up there, at the top of Rose Avenue near the Santa Monica Airport. There were three divisions when I played there: the minors, majors and seniors. Minors and majors, ages 8 to 12, played on a Little League field (45 feet from home plate to the pitching rubber, 60 feet between the bases) while the seniors, ages 13 to 15, played on a full-size field (60 feet, 6 inches to the rubber, 90 feet to first base). Now there are girls leagues too. When I started playing, we were all boys. A few girls were playing by the time my playing days ended in 1975.

If you were 8 through 12, you tried out before the season, and if you weren't drafted by a major team, you were assigned randomly to a minor team. Like most kids, I spent two years in the minors. My first year, 1971, I was placed on the Dodgers. I was given a white uniform shirt with black three-quarter sleeves and the word Dodgers in block letters across the front. On the back was my number, 6, and the name of the team's sponsor: Bobo's Barber Shop. I got a black cap with a white D on it. North Venice saw no reason to conform to actual team colors. The Cubs wore blue, the Cardinals red and the Pirates yellow, but the Yankees wore green, the Twins purple and the Dodgers black.

By my second year, when I played for the minor Cardinals, there was a new field for the minors, but in my rookie season, the minors shared the Little League field with the majors, and when that field was busy we played in the right field corner of the senior field. So we had an all-grass infield, and for an outfield fence we had traffic cones arrayed from behind the senior field's first base in an arc to deep center.

There were six teams in the minors, and we played a 20-game season. Each team played every other team four times. The Dodgers raced out to an 0-19 record. We had one good player, Mitch Nahas, who had curly hair and could hit, and when he threw he'd cock his wrist sharply, tucking the ball down on his biceps in a way that I tried unwisely and unsuccessfully to imitate. I played the outfield. If I got a base hit that year, it was due to a charitable ruling by an official scorer.

The last game of the season was against the Yankees. They were 3-16. We were the only team they'd beaten, and they were the only team we felt we could beat, though we'd failed all three times before.

Our coach, Mr. Adams -- I don't really remember his name but I think it was Mr. Adams -- had grown a mustache during the season. He was in his 40s and a regular dad type. An electrician or something. It was still a little strange, even in Southern California, for someone who wasn't a hippie or a surfer to grow a mustache. He promised us that if we won that season-ending game, he would shave it off, right in front of us.

We lived on the Westside of Los Angeles. We saw movie stars driving their cars sometimes. But my teammates and I were pretty sure we'd never seen anything quite so exciting as Mr. Adams shaving off his mustache on a baseball field. We pulled our black caps down, set our jaws and pounded our fists into the pockets of our gloves, where, after a spate of errors at midseason, Mr. Adams had made us write in black marker, THINK.

If you've ever watched 8- and 9-year-olds play baseball, you know that a spate of errors, to be noticeable among all the other errors, must be a thing to behold. But we had it now. We knew. Think. We were going to beat those Yankees.

The former players Kuenster quotes in "Heartbreakers" are pretty gracious. The members of the '72 Pirates, '75 Red Sox, '77 Royals, '86 Astros, Angels and Red Sox and all the other heartbroken clubs have, for the most part, shaken off their tough defeats. They don't have harsh feelings for pitchers who uncorked wild pitches or gave up big home runs at crucial moments, for fielders who let easy grounders trickle through their legs.

That's a good trait in baseball players, because baseball, as famously noted by the late commissioner Bart Giamatti, "is designed to break your heart."

As far as I know, this trait is shared by the 1971 NVLL Minor Dodgers, who I don't imagine harbor many bad feelings over the many errors, wild pitches, passed balls, bad throws, strikeouts and base-running errors I'm sure we all committed. Well, not Mitch, but the rest of us. But hey, baseball's like that. You win some, you lose some, some get rained out. No hard feelings.

Except for me.

My birthday is July 2. The Little League season goes from April to June. But, my family found out belatedly, the cutoff date for assigning kids their official age for the year was July 31. In other words, even though I was 7 for the entire 1971 season and a month beyond, I was really, for Little League purposes, 8 years old. We had to rush up that hill after the sign-up date and ask them to let me join a team late.

So while most kids get to play between the ages of 8 and 12, I played from 7 to 11. It's not like I'm bitter about this 30 years later or anything, but I would have gotten a lot more out of that year of baseball at 12 then I got at 7. I mean, I have seen 7-year-olds. They're cute as little bunnies, and they say the darnedest things and all, but can they go to their right on a grounder? Not even!

I should have been biding my time at 7, taking infield in the backyard, working on my swing. I'm sure I'd have had a breakout year in '76, when I should have been officially 12. That would have led of course to a major league career in which I not only would have made a fortune but would have come through with a heroic play in the World Series, thus creating for the 25 schmoes on the other team an agonizing tale that would have made a perfect chapter in Kuenster's "Heartbreakers." This doesn't bother me or anything. It doesn't.

Our season finale against the Yankees was a humdinger. I wish I could remember the details. I remember it was a foggy spring day, and I remember playing left field. I remember we played in the right field corner of the senior field, and as the seesaw battle went on a small crowd actually gathered, people coming over from the major game, amused by this war between the two worst teams in the minors, frankly hoping to see those poor Dodgers kids finally win a game.

I don't remember a single play from that game, but I'll never forget the final score: 30-27, Yankees.

Mr. Adams told us that we'd played our best game of the season and he was proud of us. His wife had brought the shaving cream and razor and a mirror. We'd played so well that he put some shaving cream on his mustache, but then he spread out his hands and said, "That's it!" A promise was a promise. He couldn't shave it off.

That losing season didn't ruin me. I've had a pretty good life so far. Great wife, wonderful friends, reasonable health. I don't make major league millions, but I do all right. Bought a new car last year. If you look in the trunk right now, you'll see an old baseball glove. It's my brother's, always was, but I still use it. In the pocket, just barely visible, it says: THINK.

Shares