I don't know if "The Servant" is the sexiest, or most suggestive, film I've ever seen. But it's the sexiest I ever saw made. And what I want to talk about here is not just the eroticism of live performance, but the very special and stealthy way in which a camera can appropriate it. To put it another way, this was the moment when I really understood how sexy it was to be filmed.

This was London in 1963, well before that strange rite called the '60s had begun. The sexual awakening of Britain was not yet; but maybe we were slowly coming out of the carnal dream that might be enacted. Somehow, American Joseph Losey knew or guessed that, and he made "The Servant" as a kind of warning and promise of what the dream might mean.

Losey was a refugee from McCarthyism. He had worked in England since the mid-'50s, doing good work, better than the Brits were doing. But "The Servant" was his breakthrough, and it had a rare breeding ground, for Losey read and liked a trashy novel in which a young upper-class gentleman is gradually seduced by his own manservant. And he gave it to Harold Pinter to turn into a script. In other words, he'd taken the germ of social-sexual insurrection and given it to not just a great dramatist but one of the best writers of cryptic, fathomless dialogue.

I was 22, just out of film school. A friend of mine, a young critic, was close to Losey and so I got invited down to the set at Shepperton for a day. I'd never been at a major studio before, and I was entranced by the way one large soundstage held all the rooms or areas of the Chelsea house where the action takes place. But, like ideas, the rooms were separated, surrounded with their own lights. It made for a house, but not a house of fluent space and domesticity. Rather, it was an analyzed house -- a house where this and then that occurred. You could trace the gentleman's decline by looking from one room to another.

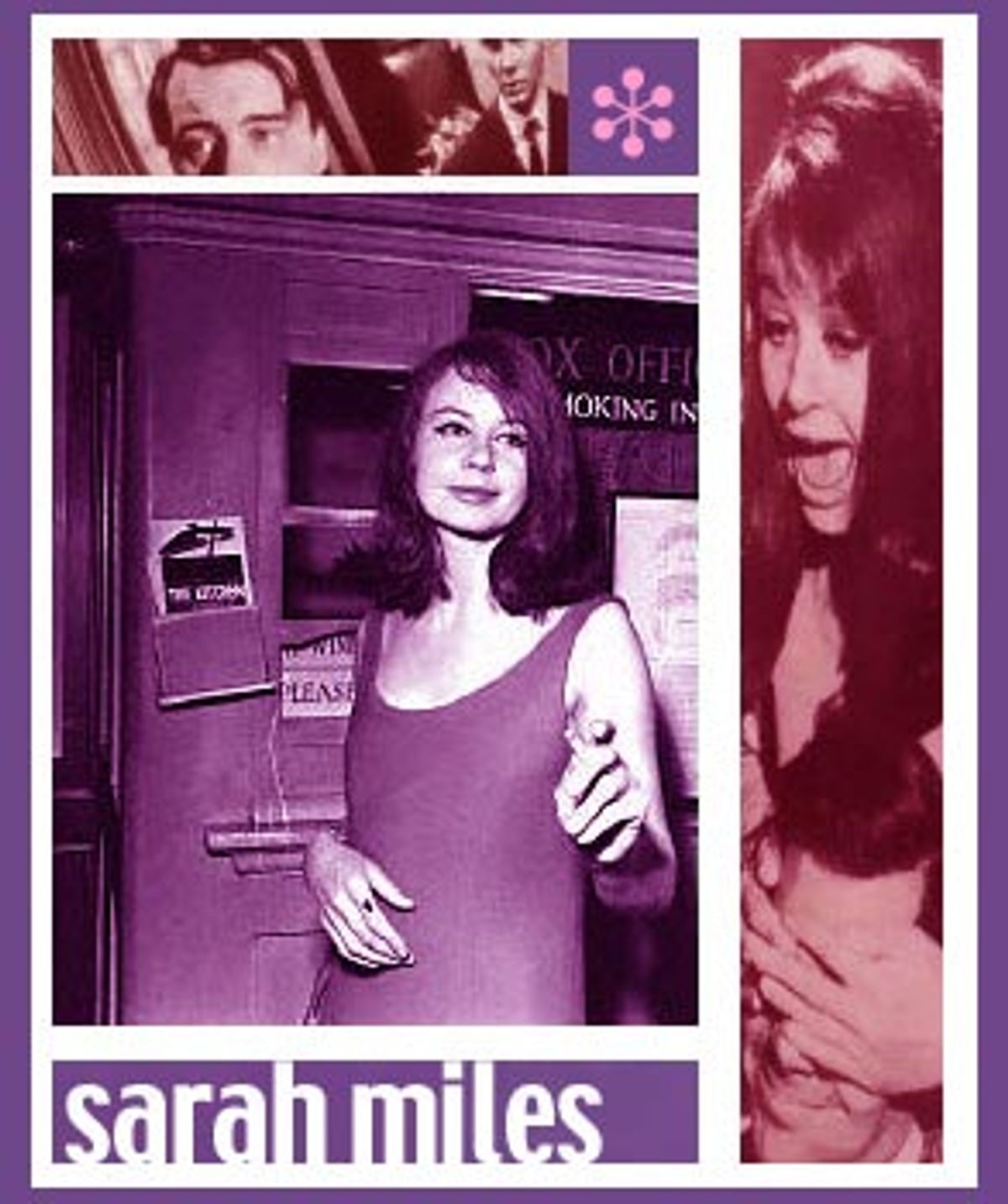

Losey shot "The Servant" in long takes in which the characters and the camera moved a good deal. Dirk Bogarde was the servant, James Fox the master and Sarah Miles the young girl from the north called down by the servant to help around the house. He said she was his sister -- events proved otherwise.

The master was called Tony and Fox then was 24. The girl was called Vera, and Sarah Miles was 21. They had fallen in love, or in sex, during the filming. Losey and the crew took this for granted. I suspect Losey had relied on it. The men who had made a lot of films knew that young actors who had to be in love for the story invariably became lovers in fact during the shooting. But Fox and Miles were relative newcomers. They'd never had such roles or such things to do, and I think they were both startled and fascinated by the way they could be themselves, and be abandoned, for the camera.

I saw a scene filmed in which Tony pursues Vera. She acts naive until he touches her. Then she gives a very throaty, knowing laugh. Leaning against a wall, they embrace.

Between takes, Losey talked to them quietly, teasing and goading them. Gently, he pushed them back out of character and into themselves, the people who were probably fucking every night. They were encouraged -- the actors, or the people (who could say which?) -- and in one take there was a moment when one of Miles' scrawny breasts was revealed. She giggled. You could not quite do that yet in a movie in 1963. She blushed -- she was only 21, and acting wild and experienced in front of all the men.

She gazed out at all the professional eyes that had seen her nakedness. And those eyes were professional enough to stay medical, as it were. You could see her grow more reckless. The takes mounted. Nothing improper was shown again. But the actress was making love to the camera. And there was Losey, tall, upright, standing beside the machine, breathing in deeply, trying to inhale her smoke, drawing it onto the emulsion of the film.

You can see and feel it in the movie still. But don't always buy the professional assurance that being on a set can be very boring. It can be -- until it becomes electric.

Shares