Amory Lovins sits down on the dais and eyes his audience of San Francisco bankers. Earth Day, April 22, is two days away, and the influential environmental scholar is late -- delayed by a visit to Sacramento where he had been kept busy advising the California Legislature, a few dozen nonprofits and Gov. Gray Davis on how to minimize the pains of California's energy crisis.

Lovins doesn't seem to be bothered or apologetic about his tardiness. After getting up to turn off an unused projector, he leans back in his chair and listens as Mike Bertolucci, president of Interface, a billion-dollar-a-year carpet company, offers an example of what Lovins was supposed to lecture about. He shows the crowd, with facts, figures and flowcharts, how Lovins' theory of "natural capitalism" works. By cutting back on the production of waste, says Bertolucci, Interface does better business. The result: Both the environment and the bottom line benefit.

After Bertolucci is finished, it's too late for Lovins to lecture but he does have time for a few questions. One audience member presses an obvious point -- given that most companies see controlling pollution as a cost, not a benefit, how does he persuade corporations to go along?

"Well," Lovins says, leaning forward, "our basic model is to urge the early adopters. We target high-profile companies in specific markets, companies that have a cultural willingness to change. But I would really love to see investors and financial analysts get involved. I'd like to see them put pressure on companies that aren't environmentally efficient."

Inspiring corporate reform is bread and butter for Lovins. He has spent most of the past 25 years teaching companies, International Monetary Fund bankers and even presidents the lessons of natural capitalism. Since 1982, his nonprofit consultancy, Rocky Mountain Institute, has offered expertise on everything from energy efficiency to the savings incurred through toilet technology improvements.

The central concept of natural capitalism -- the notion that companies that eliminate waste and become more environmentally efficient will prosper while their dirty competitors fail -- hasn't always won Lovins praise. The left has denounced him for being too optimistic, for assuming that capitalists can control their greed long enough to understand the value of cleaning up after themselves. The right, on the other hand, has argued that Lovins' focus on conservation and efficiency fails to acknowledge that resources are not nearly as scarce as most environmentalists claim.

Despite the critiques, Lovins, who can be characterized as both pro-business and pro-environment, enjoys good relations with all sides of the political spectrum. And in the current political climate -- in which the environment is moving to the center of heated debate in a fashion not seen since the 1970s -- Lovins and his profit-based call for change are ascending to higher prominence than ever before. With President Bush backpedaling on his promise to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, refusing to order cuts in the allowable concentration of arsenic in our drinking water and eager to let oil companies drill in Alaska, many environmentalists act as though Armageddon is just around the corner. Lovins, as one of the few conservationists with entree to corporate boardrooms, has become one of the movement's primary vessels of hope -- the rare messenger who won't be turned away at the door.

Yet the focus of all this attention says he wants little to do with politics. Lovins eschews the left's fevered anti-Bush paranoia. He is adamant in defense of Rocky Mountain's deliberately apolitical stance, and shrugs off concerns that the earth will long have been ruined before his theories are ever widely adopted. Lovins is hopeful for the future. As far as he's concerned, the corporate shift toward natural capitalism is inevitable; government could do more to encourage the trend and activism shouldn't be discarded, but in the long run, going green is cheaper and companies will do it for their own good. The next Industrial Revolution, characterized by dramatic transformations in resource management, is already happening and will continue to spread, he says. Not even Bush can stop it.

"It feels somewhat like the early days of civil rights," Lovins says. "The changes are here, now, and on the way."

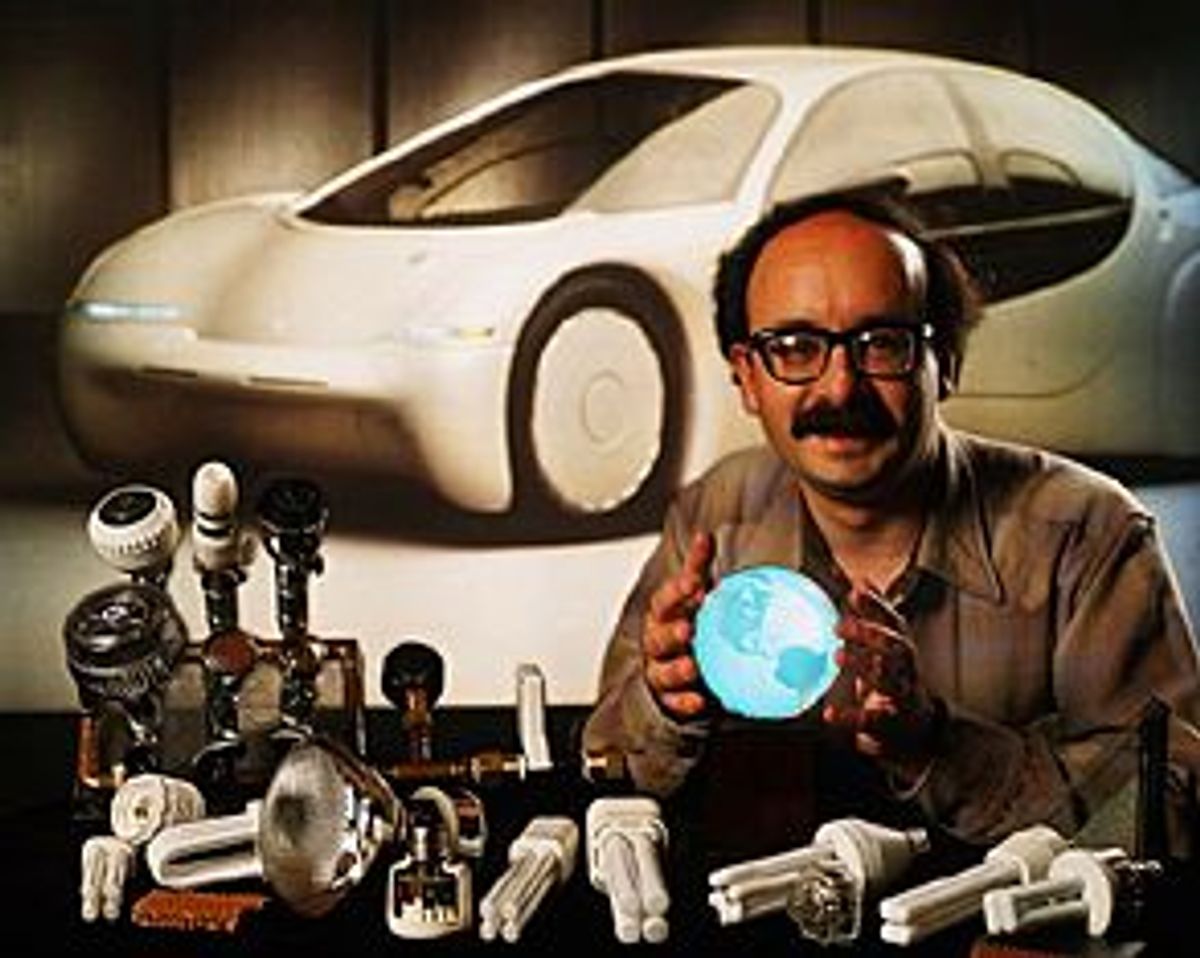

Lovins is about 5-foot-8, with a slight paunch, a balding pate and a thick, dark mustache that barely moves when he talks. At the San Francisco investment advisors conference he wears a blue suit that lacks the slightest thread of Wall Street panache. Worn and wrinkled, it is a perfect match for his stiff, polyester, triangle-adorned tie.

His attire is more appropriate for a professor than an activist or a businessman, but then again, Lovins never intended to be anything but a scientist. Born in Washington, D.C. -- "I was actually the ugliest baby born in Garfield Memorial Hospital," he jokes -- Lovins exhibited an early interest in how things worked. His mother, a social worker and editor, schooled him in the communication of ideas, while his father, an electrical engineer, and his older sister, Julie, a computer scientist, taught Amory to tinker.

When Lovins got to Harvard in 1967, he chose to study physics. A self-described apolitical nerd in college, he remained concerned largely with atomic particles rather than with protests. But he did begin to develop a concern for the environment. "I slowly decided to move from academia to activism," he says. "In 1971 I was doing graduate work in physics at Oxford, and the problems I was working on were interesting, but not nearly as important as the [environmental] ones I was reading about. So it gradually occurred to me that if I wasn't part of the solution to those problems, I was part of the problem. So I left academic life."

Lovins immediately joined up with environmental pioneer David Brower, longtime executive director of the Sierra Club, founder of the Earth Island Institute and, says Lovins, "the greatest conservationist of this century." (Brower died in November at the age of 86.) The match didn't initially make a whole lot of sense. Brower was a 49-year-old radical Californian who loved climbing mountains almost as much as he loved shouting out for protection of the great outdoors; Lovins, on the other hand, preferred a quiet life of the mind. But for the next decade the two men worked closely together, Lovins in London, Brower in the U.S. "I learned how to be effective from Dave," Lovins says, looking back. "I also learned fairly early on that when I went to see Dave, I better bring a passport and a toothbrush because I never knew where he'd whisk me off to."

Lovins shared Brower's sense of outrage at how the environment was treated, but he didn't mirror his mentor's pugilistic approach to change. Lovins instead became the staid voice of environmental finance. The books and articles he wrote in the '70s applied economic reasoning to earthly problems. He warned of the costs of dependency on foreign oil, showing how much money could be saved by decreasing demand. He argued that nuclear power was uneconomic, and insisted that companies should focus on creating energy-efficient products not just because it's right but also because it helps the bottom line.

Lovins' ideas elicited both praise and criticism. The left began to think they had found a powerful, important new ally. His work was "seminal," says David Orr, author of "Earth in Mind" and an environmental studies professor at Oberlin College. From the start, adds John Passacantando, executive director of Greenpeace's U.S. division, Lovins "has laid out a phenomenal, green, sustainable path."

But economists on the right saw serious flaws in Lovins' work. "He got a bad rap in the '70s because he analyzed the 1973 energy crisis without mentioning the role of price controls," says David Henderson, a research fellow with the Hoover Institute and a former energy policy advisor to President Reagan. "That's just Econ. 101, the fact that price is what gets people to conserve and that Jimmy Carter's dedication to price caps affected the crisis. But he just ignored it. That, probably more than anything else, made a lot of economists think that Lovins didn't know much about how capitalism worked."

The concept of natural capitalism, then, can be seen as Lovins' attempt to prove that he does know how capitalism works, while at the same time keep laying out that path to sustainable development. As explained in 1999's "Natural Capitalism," co-written with Hunter Lovins (now his business partner and ex-wife) and Paul Hawken, the term points forward to the next, newer, cleaner Industrial Revolution. Lovins argues that environmental concerns are being ignored not so much out of corporate greed but rather because of inertia.

The original Industrial Revolution was characterized by a plenitude of natural resources and a scarcity of technology and people, contends Lovins. Everything from corporate culture to tax laws reflected the view that companies would always have two things: enough money to buy natural resources and enough "elsewheres" to dispose of them afterward.

Now, however, those assumptions are proving false. If one takes into account all the waste produced in the United States by corporations and individuals, Americans generate 1 million pounds of trash per person per year, writes Lovins. Eventually, there will be no new places to put it. Meanwhile, as global warming continues, our climate is failing to purge the toxicity of industrialization, and resources such as water are proving to be far more difficult to clean and maintain than previously imagined.

In this economic environment, Lovins argues, companies must follow four principles to succeed. They must increase the productivity of natural resources, model industrial processes after biological systems to minimize waste, sell service-based solutions rather than products and reinvest in natural capital.

Many companies are already recognizing the value of natural capitalism, Lovins argues, citing, for instance, DuPont. The chemical company's environmental costs dropped from a high of $1 billion in 1993 to $560 million in 1999, according to its environmental progress report. Most of the savings came from pollution prevention programs that lowered waste treatment and disposal costs. But DuPont has also learned how to use less fuel, which in turn improves the bottom line, Lovins says. "They're saving at least $6 for every ton of CO2 they don't put in the air, because the carbon is the fossil fuel they no longer need to buy," he explains. "All those CO2 molecules have a price tag, namely someone's fuel bill."

Southwire Corp. -- a billion-dollar wire and cable manufacturer -- has followed a similar path toward energy efficiency, says Lovins. Over the past 20 years, the company has invested in new energy-efficient motors and better light bulbs. Engineers also found a way to cut down on the creation of scrap metal and retooled the furnaces so that they capture and reuse heat that once exited through smokestacks. "We used to pay about $22 million to $25 million a year to keep things running," says Lee Hunter, the company's vice president of energy. "Now, we pay about $18 million."

Then there's Interface. Bertolucci, speaking before the group of investment advisors, says that his company has put several reforms in place. Interface has purchased solar panels, reengineered its manufacturing process in a way that reduces the amount of toxic chemicals used and shifted from products to services, offering not just sales but also industrial-carpet leases. All of these moves help the environment: American companies and individuals trash 3.5 billion pounds of carpet every year. By making a few changes, by the end of 2000, Interface had eliminated more than $165 million in waste from products and processes.

These success stories, cited repeatedly by Lovins in lectures, in books and on his Web site, are not entirely complete. Interface, for example, despite offering leases for the past three years, has managed to sign up only four customers -- a drop in the revenue bucket. Lovins' stories also gloss over or entirely ignore a key source of natural capitalism's improved bottom lines -- government. Under laws passed in the 1970s, and maintained through the Clinton era, companies that reduce pollution receive financial credits. Part of DuPont's improved bottom line comes from these federal programs, says Leslie Cormier, a DuPont spokesperson, although DuPont doesn't break out government-related cost savings from pure market savings, so it's impossible to know exactly how big a role government has played.

Government incentives and regulations play an important role in encouraging corporate responsibility, says John Holdren, an environmental policy professor at Harvard. Lovins tends to be too optimistic, says Holdren; he ignores the fact that "industry is not, by itself, going to worry enough about overdependence on oil, or about greenhouse gas emissions that affect the climate." Plus, even if capitalism eventually does realize that protecting the environment is in its own interest, how long should society be expected to wait? Should the environmentally conscious simply watch as places like Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge are slated for the oil industry's auction block? Should they really believe that the Bush administration is simply a distraction, a bump in the road to environmental Utopia?

Holdren and more radical environmentalists, who sometimes call Lovins' stance "wishy-washy" or "naive," are concerned that Lovins assigns too much control to companies and consumers. Like Henderson, they argue that government can dramatically alter the future course of world events. Some even say that Lovins, by diminishing the importance of government, threatens to hurt the environmental cause by discouraging activism.

Lovins doesn't appear to be bothered by such criticism. He maintains an unvacillating faith in the markets. No one, he insists, not Jimmy Carter, nor President Bush, can affect the environment as much as pure, powerful, plain-and-simple capitalism.

"Government is important, and yes, people in government are often eager to use power for purposes we don't agree with," he says. "But the two biggest springs of action are companies and communities. They're big enough to get things done and small enough not to trip all over themselves."

"Natural capitalism is extremely profitable today," he adds in an e-mail. Indeed, Southwire confirms that not a dime of its savings comes from government credits. And at Interface, Bertolucci says, the vast majority of cut costs come directly from the market.

Today, "even when nature (and people) are valued at roughly zero," Lovins says, companies are still saving millions of dollars by becoming more efficient. "The business case for natural capitalism, in both short-term profitability and stunning longer-term competitive advantage, comes from dramatic reductions in private internal costs through eliminating waste, making only things people want to buy, aligning incentives with customers and reinvesting in the most productive forms of capital. In short, orthodox economics taken seriously."

Lovins' retort might not be enough for some environmentalists, but many experts -- including radicals like Passacantando and conservatives like Henderson -- defend Lovins with passion. They primarily praise his results and effectiveness. Lovins hasn't just preached the message of natural capitalism, they argue, he has also practiced it. Though he has written 27 books and won a series of awards including a MacArthur "genius" grant, he's not just a scholar. He's also a CEO.

In 1982, he left the Earth Island Institute and with a few like-minded "resource analysts," including Hunter Lovins, founded the Rocky Mountain Institute. The Snowmass, Colo., "think and do tank," Lovins says, focused initially on energy policy. But soon its palette broadened. Today, with a $5 million annual budget, the nonprofit's 45 employees study and offer consultation on everything from renewable energy to climate control to water policy. Lovins alone, who tends to pack his schedule more tightly than a sardine can, pulls in as much as $20,000 a day as a consultant.

The building itself reflects Lovins' values. Built into the side of a hill, the 4,000-square-foot edifice uses solar power and superthick insulation to save energy. Each day, the building saves about $6 worth of energy, "economically equivalent to producing a barrel of oil every three days," according to the Rocky Mountain Web site.

Lovins' efforts don't stop there, though. Along with helping major Fortune 500 companies, he has also spun out a start-up of his own, Hypercar Inc. The name hints at the product: a carbon-fiber sports utility vehicle that runs on a fuel cell, allowing it to get the equivalent of 100 mpg while emitting only water. Models of the vehicle can't be found except on computer screens, yet in many ways, Hypercar is the culmination of Lovins' ideals.

He first started thinking about the car in the early '90s and spent several years publishing tomelike academic studies on its viability. He had hoped that an automaker would pick up the idea. But in 1999, he gave up on persuasion and formed a company of his own. Hypercar won't challenge Detroit anytime soon. But just as Rocky Mountain has attracted a diverse array of corporate clients, so too has Hypercar sparked the interest of a motley crew of investors. BP Amoco, for example, has invested $500,000, and Sam Wyly -- the Texas billionaire who funded an ad attacking then candidate John McCain for ignoring solar power during last year's presidential campaign -- has tossed in a cool million. With a war chest of $4.3 million secured, and with high hopes for a steady stream of more cash, Lovins figures that Hypercar production is only a few years off.

But history is littered with the stories of failed automotive entrepreneurs -- does anyone really think Hypercar has a chance?

Not even Lovins is sure. But what's interesting about Lovins is that Hypercar is often all he wants to talk about. He passes out Hypercar fliers wherever he goes. And despite all the attention he's getting these days, despite his status as one of the environmental movement's most powerful political forces, despite the respect he gets from corporate America and the GOP, Lovins seems more concerned with cars than with Alaska or with electricity. Detroit forms the geographical locus of his mind, not Washington.

Which only makes sense, says Dan Kammen, founding director of UC-Berkeley's Renewable and Appropriate Energy Lab. "Amory is a true visionary," he says. Even if the Hypercar never makes it out of development, even if Lovins tends to be too optimistic, his general market-based approach deserves to be lauded. Simply put, he says, "we need to catch up with Amory more than he needs to become realistic."

This story has been corrected.

Shares