For Amy Kapczynski, the turning point came in Durban. When she arrived in the South African city for the World AIDS Conference last July, she was greeted by 5,000 demonstrators demanding access to medications that could prolong or save their lives. Blacks and whites walked side by side -- an image of how in a country once separated by apartheid both races have come together to fight a common enemy. They marched behind a banner emblazoned with the words that have come to symbolize the struggle against the deadly disease in South Africa: "Pity" crossed out, with "Medication For All" printed beneath.

"It was amazing, there was incredible energy," the 26-year-old law student recalls. "South Africa is such an astounding place -- you can still feel the living history of the revolution taking place in their country. The people are incredibly politically literate, active and motivated." The activists' slogan, with its appeal to justice and rejection of pity, fired Kapczynski's imagination. "It's not about feeling bad and doing things out of guilt," she says. "People have a right to medication. They have a right to dignity and to have their own lives and the highest attainable standard of health."

Kapczynski attended a shadow conference for women that brought together participants from the United States, Europe and South Africa. It was at those meetings, Kapczynski says, that she was viscerally jolted into an awareness of the gulf that separates the reality of AIDS in the industrialized world from that in impoverished countries like South Africa, where the vast majority of people live in abject poverty. As the panel discussed the side effects of taking dozens of anti-retroviral drugs each day, it suddenly dawned on her that many of the women listening to the discussion didn't have access to any drugs whatsoever. HIV-positive participants from Germany and the United States might suffer nausea and fatigue, but most of them were going to live for years or decades. Those from South Africa were going to die, some of them very soon. "The divide was jarring and disturbing," she says. "It was an ethically and emotionally impossible feeling. I just had the feeling that this can't continue. It's unjust."

The crowning irony of the whole situation, Kapczynski realized, was that the few South African women at the meeting who were actually receiving treatment were on clinical trials that had been set up by pharmaceutical companies -- the very companies that were trying to sue the South African government to keep it from importing or producing cheap generic versions of patented drugs.

Kapczynski returned from the conference to start her first year at Yale Law School. But along with plunging into textbooks on torts with the rest of her classmates, she took on a bigger project. Working with the Nobel Prize-winning organization Doctors Without Borders, she achieved something that had never been achieved before: She helped launch a campaign that ultimately led Yale and Bristol-Myers Squibb, one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world, to pledge not to enforce the patent on d4T -- a crucial drug in HIV treatment, sold commercially under the brand name Zerit -- in South Africa.

It was a monumental victory: No pharmaceutical company had ever relinquished a patent on an AIDS medicine. Even more crucial, perhaps, was the effect on other pharmaceuticals. The 39 leading companies, worried at the prospect of losing control of their patents -- and terrified at the possibility that providing drugs free or almost free to Third World countries would eventually undercut drug prices in developed nations -- had filed a lawsuit against the South African government, seeking to force the government to overturn an unenforced 1997 law allowing the public health ministry to override drug patents in the event of a national health emergency. Since passing the law, the South African government has never declared such a state of emergency. But even as it pressed the lawsuit, Big Pharm, as the pharmaceutical industry is known, knew that public opinion could turn harshly against it if it was seen as preventing access to lifesaving drugs in the name of corporate greed.

That, in fact, is exactly what happened. Battered by criticism, on April 19 the pharmaceuticals announced they were dropping their lawsuit against South Africa. Yale and Bristol-Myers Squibb's decision was critical in turning the public relations tide. With a major pharmaceutical having accepted the principle that normal corporate behavior should not be maintained in the face of the devastating scale of the AIDS epidemic -- more than 4.7 million people are HIV positive in South Africa alone -- it had simply become too damaging for the other companies to continue their legal battle.

The battle over d4t is just one skirmish in what is becoming a monumental showdown over the future of global healthcare. On one side stand activists and critics who say that giant pharmaceutical companies have a moral responsibility to provide their medicines at reasonable prices, not just in the Third World but in developed nations. Their opponents, like conservative journalist Andrew Sullivan, argue that these critics are really anti-capitalists in humanitarian garb, and that the profits the pharmaceutical companies make are needed to finance the costly R&D that brings new drugs into the market. It's a confrontation whose emotional stakes are raised by the AIDS nightmare, which has killed 22 million people in Africa alone.

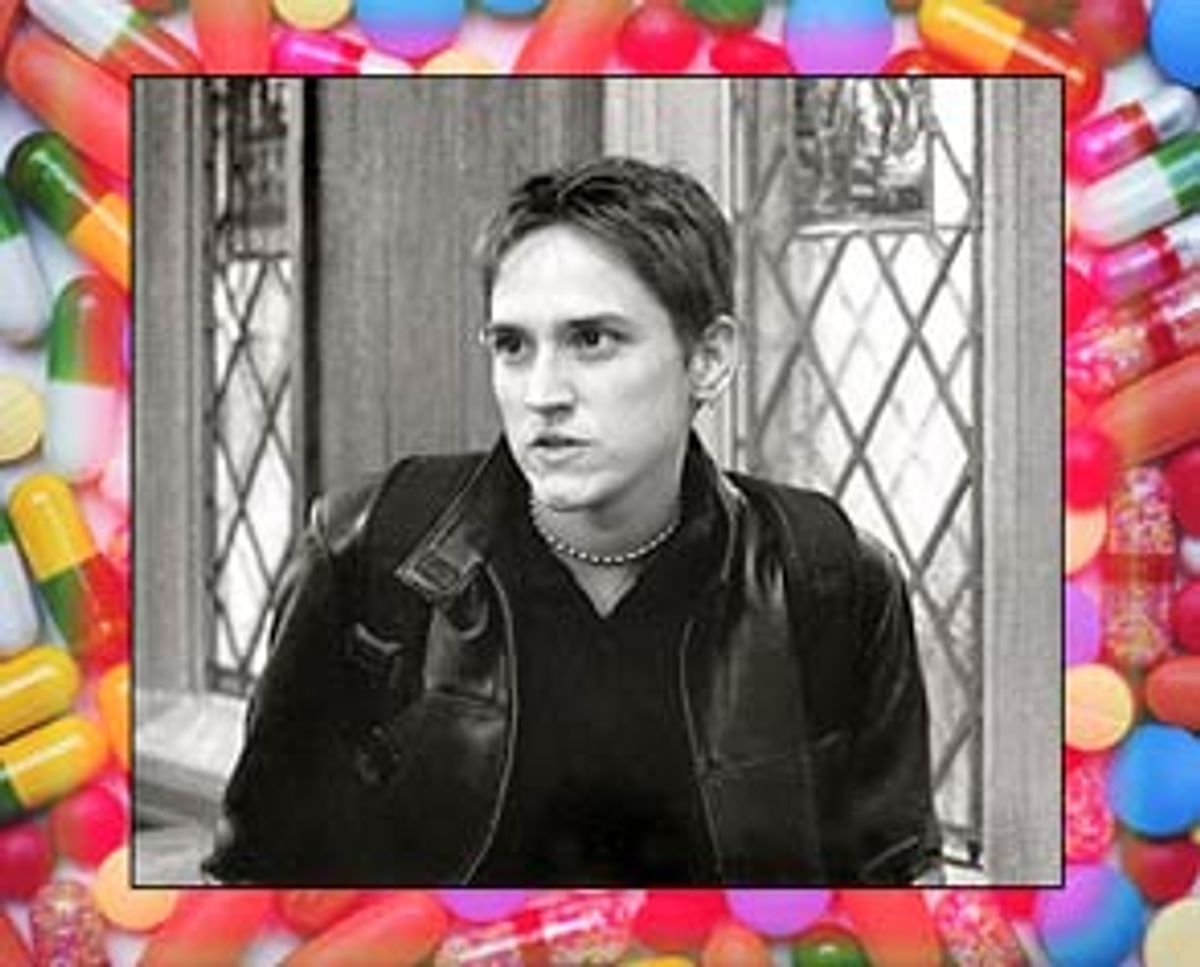

Toby Kasper, the head of the Access to Essential Medicines Program for Doctors Without Borders who worked with Kapczynski in her fight, said, "The developments at Yale could not have happened without Amy Kapczynski. She was driving things there and did a great job just getting out there and talking to the right people." Speaking from his office in Cape Town, he hailed the decision as "historic. A company has never given up its patent for a drug like this. Universities make a lot of money on these patents, so they're hesitant to give up their right. But Yale acted out of fear of public relations and the fear of a student uprising. Besides, AIDS is a graveyard for corporate P.R., and it's an area that could cause potential harm to a university's P.R." With her close-cropped brown hair, pierced eyebrow and penchant for wearing Carharrts and T-shirts, Kapczynski looks more like a prototypical activist than a lawyer. But it was her research ability, media savvy and negotiating skills that helped broker the deal. Kapczynski is no newcomer to the field of AIDS-related legal issues -- she worked for an AIDS organization in London after studying at Cambridge as a Marshall scholar and worked as a researcher on a CBS "60 Minutes II" special on the AIDS epidemic in Africa. She had seen the devastation AIDS has wrought in South Africa during a trip there on behalf of a human rights organization at Bard College.

Doctors Without Borders' Kasper met Kapczynski at the AIDS conference in Durban. His organization had sought permission from patent holders of AIDS drugs for South Africa to import or produce generic versions, using Brazil as a model. In Brazil, less restrictive intellectual property laws allow for the generic production of HIV drugs: More than 100,000 patients there are being treated with a generic cocktail manufactured by Brazilian companies. The Indian generic drug manufacturer Cipla has said it could produce a three-drug cocktail for $1 a day per patient in South Africa. The cocktail, which is made up of a generic version of Zerit and two other anti-retroviral drugs, would cost $350 a year per patient -- a fraction of the $10,000 to $15,000 that patients in the United States or Europe must pay for the treatment. DWB's strategy was to press its case directly with the universities and corporations that hold the key-use patents for the drugs it needed.

Kasper learned that Kapczynski was in law school and was interested in working with the organization on legal issues that people with HIV or AIDS face -- family law, rights, access to healthcare, intellectual property and other problems. After Kapczynski returned to New Haven, Kasper contacted her and another Yale student he knew from his undergrad days at Harvard, Marco Simons, by e-mail, alerting them that he planned to send a letter to Yale requesting that they grant a d4T license to his organization. He asked them to help mobilize faculty and students.

Kapczynski's first move was to identify potential university allies. Of these, the most crucial proved to be the compound's inventor, Dr. William Prusoff. Going into the meeting with him, she had no reason to be wildly optimistic. The 80-year-old pharmacologist, who had discovered that d4T was an effective AIDS medicine in the 1980s, had made millions off the patent, and often scientists are unwilling to pressure pharmaceutical companies, which provide them with funding and revenue opportunities. "We didn't expect him to be as friendly and receptive as he was," she recalls. But Prusoff turned out to be not only receptive but downright outspoken in his support of the students.

Meanwhile, Yale had rebuffed Doctors Without Borders' request. Jon Soderstrom, managing director of the Yale Office of Cooperative Research, which manages patents held by the university, sent a Feb. 28 letter to the group stating, "Yale has granted an exclusive license to Bristol-Myers Squibb, under the terms of which only that entity may respond to a request." The d4T patent has been a cash cow for Yale, which nets about $40 million a year from its licensing agreement -- almost all of that money coming from developed nations like Germany, the United States and France.

Kapczynski began doing legal research, trying to find out the terms of Yale's licensing agreement with Bristol-Myers Squibb. She met with School of Public Health dean Michael Merson, who formerly headed the AIDS program of the World Health Organization and, Kapczynski believed, would be sympathetic to DWB's request. Through another professor, Kapczynski requested a copy of the contract the university had with Bristol-Myers Squibb, which officials declined to release. At the same time, she put reporters at the Yale Daily News on the trail of the story. The student paper published its first story on the subject on March 2. "The story had a strong mobilizing effect," says Kapczynski. A group of students in the Graduate Student Union -- which had already been campaigning against Yale's relationship with corporate sponsors -- circulated a petition calling on the school to ease its patent. They managed to collect 600 signatures from students, professors and researchers on campus. The students also assailed Yale for its close ties with BMS -- the company donated $250,000 to the school in 1999.

Looking back, Kapczynski says that she didn't realize in the middle of the struggle just how big the stakes were. "[At first], the project just felt like something on our task list. It absorbed lots and lots of time. We were just trying to figure out how to make things happen, and we were doing it on the fly," she says. "We didn't realize how big of a deal it could potentially be."

On March 9, armed with Kapczynski's research into the licensing contract and with help from members of the Yale AIDS Action Coalition (of which Kapczynski is a member), Kasper wrote back to the university, arguing that the deal violated Yale's own licensing provisions, which require that such deals "benefit society in general" and that they "protect against the failure of the licensee to carry out effective development and marketing within a specified time period." By ignoring 90 percent of the market for d4T, Kasper argued, the university was not serving the public interest.

As the negotiations between the university and Bristol-Myers Squibb continued, Prusoff jumped into the fracas, telling a New York Times reporter in an interview on March 11 that he would "strongly support" the campaign by students to relax the patent in order to enable wider distribution in South Africa. "I wish they would either supply the drug for free or allow India or Brazil to produce it cheaply for underdeveloped countries," he told the Times. "But the problem is, the big drug houses are not altruistic organizations. Their only purpose is to make money."

Prusoff's statements were the last straw. On March 15, Bristol-Myers Squibb announced that it would not enforce its patent license on d4T in South Africa. In a statement, executive vice president John McGoldrick said: "This is not about profits and patents; it's about poverty and a devastating disease. We seek no profits on AIDS drugs in Africa, and we will not let our patents be an obstacle." Though a BMS spokesperson would later tell the Wall Street Journal that the student protests did not compel the decision-making process, the mere timing of events suggests they did.

Kapczynski says a professor, whom she would not name, told her that the public comments made by Prusoff had embarrassed the university. "They were distraught by the editorial he wrote and how publicly he was willing to talk," she recalls. "They had a lot to fear. Drug companies are very reluctant to discuss patents. They're a big funder of university research, and maintaining good relations is important. The universities don't want to be difficult to work with for the pharmaceutical companies because they want to market their compounds to them."

Considering these factors, the speed with which the university moved astonished Kapczynski. "I didn't expect it to happen as quickly as it did. It was bewildering, and still sounds a little too good to be true," she says, "Still, they were thinking about a price cut anyway, so it made sense. They're trying to save their public image. And I imagine a student movement was on the radar for them. People have been organizing to encourage universities to divest themselves of pharmaceutical interests in student groups and on e-mail lists. Students are becoming strategic in organizing around issues in which their universities are involved."

The Yale battle is just one of several in what has become an international campaign to force universities and pharmaceuticals to change their business practices in dealing with the AIDS pandemic. A similar effort is now underway at the University of Minnesota, which holds the patent for Abacavir, sold under the brand name Ziagen and exclusively licensed to pharmaceutical giant Glaxo Wellcome. Carbovir, one of the main compounds found in Abacavir, was first synthesized by Robert Vince, a professor of medicinal chemistry, in the late 1970s. The university sued Glaxo Wellcome for patent infringement in 1998; the case was settled, and Glaxo Wellcome agreed to a one-time settlement of $7.25 million in 1999. The university expects royalties on the patent to exceed $300 million, which it wants to reinvest in AIDS research.

In March, as the debate over university patents convulsed Yale, University of Minnesota doctoral student Amanda Swarr started a campaign on the Minnesota campus, calling for it to ease its Abacavir patent. Like Kapczynski, the 28-year-old Swarr is a veteran of AIDS activism. She spent a year and a half in South Africa working on her doctoral thesis in women's studies and volunteering as a member of the global Treatment Action Campaign.

"Students here are feeling like there's a local connection," Swarr says, explaining why she has been successful in mobilizing against the university. The issue, she says, goes beyond AIDS drugs and pharmaceutical companies. "We're dissatisfied with the corporatization of the university. Corporations are giving universities more money than they ever have, and yet undergraduate education is deteriorating and students face tuition hikes on campuses."

But pharmaceuticals, in particular, have drawn the anger of students -- and other critics. The novelist and journalist John le Carré took shots at Big Pharm in his latest book, "The Constant Gardener," and blasted the relationship between universities and the pharmaceutical industry in a recent essay in the Nation. "Consider what happens to supposedly impartial academic medical research," le Carré wrote, "when giant pharmaceutical companies donate whole biotech buildings and endow professorships at the universities and teaching hospitals where their products are tested and developed. There has been a steady flow of alarming cases in recent years where inconvenient scientific findings have been suppressed or rewritten, and those responsible for them hounded off their campuses with their professional and personal reputations systematically trashed by the machinations of public relations agencies in the pay of the pharmas."

On April 16, Swarr and members of the student-run Coalition for Access to Education, which opposes what they charge are the university's sweetheart deals with corporations, sent a letter to officials demanding that the university make a binding statement that it will not enforce its patent in developing nations. Nongovernmental organizations like HealthGAP, South Africa's Treatment Action Campaign and Oxfam America also sent letters of support, asking the university to heed the students' demand. The university issued a statement on April 19 saying that it would "welcome a price reduction" in Ziagen. Though the statement offered praise for Yale's decision not to enforce its patent in South Africa, it did not offer to do so itself. In an interview with the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, the university's lawyer, Mark Rotenberg, said: "We don't believe that giving up our royalty ... is going to have much of a public health impact."

Swarr, who is heading a petition campaign that she hopes will garner 20,000 signatures, advances the same legal argument used by DWB and Kapczynski, saying "Glaxo Wellcome's high pricing keeps the university from fulfilling its mission of serving the public interest." She believes the university will ultimately relent and pressure Glaxo Wellcome to abandon enforcement of the university's patent. "I think they feel like they need to move on it. They're getting national and international attention on the issue. Abandoning enforcement of the patent would be win-win for the university, too, because it gets almost no royalties from the sale of Ziagen in developing nations."

Others are less sanguine. Jamie Love of the Consumer Project on Technology, who has done extensive research on patent holdings for the most crucial drugs used in AIDS treatment, says there are multiple patent claims on Ziagen, held by both the university and Glaxo Wellcome, that will be extraordinarily difficult to untangle. He points out that there's also bad blood between the university and the corporation over the 1998 lawsuit.

The current front line in the war to make AIDS drugs affordable in poor nations is South Africa, but it will soon shift to Brazil, India and Thailand. Intellectual property laws are lax in these countries, and all three produce generic cocktail drugs. Under the World Trade Organization's Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), those countries must tighten up their intellectual property and patent laws by 2005. TRIPS includes a provision that allows countries to temporarily suspend patents during a national emergency, but South African President Thabo Mbeki has so far refused to do so. Under TRIPS, it will be easier for corporations to pressure the governments of countries like the United States, which has stricter laws, to file grievances against developing nations with the WTO. During the 2000 election, according to figures supplied by the Center for Responsive Politics, Big Pharm was the 12th-largest industry contributor, pouring over $26 million into the coffers of the parties, presidential campaigns and congressional campaigns. So it wouldn't be difficult for the pharmaceutical companies to find sympathetic ears in Congress and at the White House.

The real reason the pharmaceutical industry is trying to hold the line on its AIDS patents in impoverished nations is its fear that the Third World battle is simply the thin end of the wedge and that the activists' real goal is universal price controls on drugs -- in effect, socialism justified by overpowering moral arguments. Making AIDS drugs available at cost in impoverished nations facing one of the greatest plagues in human history would seem to be morally imperative -- but, the drug companies' defenders argue, it's a slippery slope. Where do you draw the line? Tactically, the industry fears that once it can be shown that AIDS drugs can be produced cheaply in Third World countries, Americans will demand the same.

In fact, activist groups like the Consumer Project on Technology are fighting for the right to produce or import generic versions of d4T, at cost, for distribution in the U.S. and other industrial nations -- effectively preventing Big Pharm from making any money from sales of AIDS drugs in those countries. Student groups on campuses from Yale to Minnesota to Harvard have been organizing around the issue -- both on campus and through e-mail list-servs like the one maintained by Healthgap.

A look at the numbers shows why the battle over AIDS drugs has very little to do with developing countries (contrary to what media coverage suggests) and everything to do with protecting the American and European markets. According to market research firm IMS Health, of the $3.7 billion spent on AIDS drugs in 2000, the lion's share, $2.6 billion, was paid out in the United States. The Europeans racked up $950 million in sales, while Africa, Asia and Australia spent only $108.5 million -- a small fraction of the total.

Critics of the activists charge that their real agenda is gaining control of the entire pharmaceutical industry. "What's happening on these campuses is a tragedy," says Robert Goldberg, a healthcare policy analyst at the National Center for Policy Analysis. "Students like Amy Kapczynski at Yale aren't really thinking about AIDS -- it's capitalism that they see as the real virus. AIDS is a glamorous disease to worry about." Arguing that corruption and ignorance will doom AIDS efforts in South Africa, Goldberg notes that drugs were made widely available for free in Russia and Africa to treat tuberculosis and malaria, but that has done "little to stop a disease that claims 2 million lives a year." With AIDS drugs, he argues, the outcome wouldn't be much different: "You could dump all the AIDS drugs and cocktails for free in Africa. Half of the drugs would be stolen, a quarter unused or improperly used." Goldberg is also concerned about generic AIDS drugs slipping across borders into Europe and the U.S. "There's a short-term problem of these drugs showing up in Europe through gray markets," he warns. "Government medical agencies tend to turn a blind eye toward parallel imports from Greece and Turkey. A company like [India's] CIPLA could export its generics, relabel them" and funnel them through this market.

"In this country, groups like [Consumer Project on Technology] see the South Africa campaign as a way to get lower prices here," Goldberg goes on. "This is simply First World selfishness being manifested, using the Third World as a backdrop. As we've seen, minutes after the victory in South Africa [when the pharmaceutical companies dropped their case], the government said it was not going to use the cocktails." Indeed, just days after the case was dropped, South African Health Minister Dr. Manto Tshabalala-Msimang stated that supplying AIDS drugs would not be a government priority, despite the drastic reduction in prices. Instead, the government will focus on treating opportunistic infections and improving nutrition among HIV patients. South African President Mbeki has in the past expressed concerns about the safety of cocktail treatments and even questioned publicly, to international dismay, whether HIV is the true cause of AIDS.

Critics like Goldberg, pointing to South Africa's weak healthcare infrastructure, also fear that improper distribution and consumption of the cocktail drugs could lead to more resistant and deadly strains of HIV. Instead of emphasizing cocktails, Goldberg proposes that the African governments institute prevention and education programs and make widespread use of AZT, which is inexpensive to produce and has been shown to reduce childbirth transmission by as much as 50 percent -- a plan that could certainly make the biggest difference in the long run, since it would reduce the infection rate.

Above all, Goldberg argues that reduction of pharmaceutical profits will result in diminished research and, in the end, fewer lifesaving drugs coming onto the market. "This populism is simply a U.S. domestic political effort to suck profits out of the pharmaceutical companies by reducing worldwide price through eliminating intellectual property protection," he says. "In the short term, it sucks profits; in the long term it will result in a reduction in research funding as we saw with tuberculosis and malaria drugs when the original patents expired."

His argument is echoed by conservative (and HIV-positive) journalist Andrew Sullivan. In an October essay in the New York Times Magazine, Sullivan wrote, "It would be wonderful if we could make the newest drugs affordable for anyone who needs them and keep the lifesaving research going. But cut prices and you cut profits. Cut profits and you cut research and development. Cut research and you slow new drug innovation. You may get cheaper and more widely available drugs in the short term, but you'll also get worse drugs in the long term, and risk ending the greatest era in research in memory. Don't big pharmaceuticals make enough money to take a hit? Sure, their profitability is slightly higher than some other industries -- but that barely offsets the unique risks the drug industry has to take. Of more than 5,000 potential medicines tested at some point in the lab, on average only 3 get into clinical trials, and only 1 is approved for patient use. In all, only 30 percent of drugs make enough money to recoup the cost of their own research, and the average time it took to bring a new drug to market in the 1990s was close to 15 years, at an average cost, according to Boston Consulting Group, of $500 million."

New York University professor Merrill Goozner challenges these assertions. In an online debate with Sullivan on Slate, Goozner, who covered the drug industry for the Chicago Tribune for years, described the claim that the industry spends $500 million to bring a new drug to market as "preposterous."

"This bogus number is based on an industry-funded study that assumes all industry research is relevant and all its new drugs are clinically important," Goozner wrote. "Nothing could be further from the truth. Much industry research is aimed at bolstering marketing claims for its existing products. And nearly half is aimed at developing minor variations of existing drugs. Indeed, one of the authors of the original study has corroborated my own estimate that in excess of 40 percent of industry R&D is aimed at producing such 'me-too' drugs." Besides, Goozner argued, a significant chunk of industry research is funded by the U.S. government. "The National Institutes of Health will spend $2.3 billion in AIDS-related research next year. PHRMA, the industry trade group, proudly claims its members have 73 AIDS drugs in development and then quietly admits that most firms are receiving substantial government aid (usually through collaboration with NIH-funded researchers) as they try to move them from the laboratory to the marketplace."

According to Goozner, the bottom line isn't about whether pharmaceutical companies should be run as for-profit endeavors. "It's the size of the rewards that are being questioned. And when it comes to lifesaving drugs whose price puts them beyond many people's grasp even here in the good ol' USA, that's a question whose answer should be based on facts."

Kapczynski denies that distribution of AIDS drugs in Africa will be as chaotic and disorganized as critics like Goldberg claim. "No one is offering to dump anything out of airplanes. This is a tired red herring," she says. "There are serious discussions going on at the moment in the U.N. and elsewhere about bulk procurement and distribution systems for AIDS drugs to ensure that they get to the people who need them."

As for the arguments that the pharmaceuticals won't be able to do R&D and produce new drugs if they can't maintain current profit levels, her response boils down to "Show me the money."

"It may be true that the American people will now start to demand an honest accounting of the way prices are set in this country," she says. "If drug companies were willing to open their books and discuss how much they actually spend on the development of particular drugs, we could start to make reasoned decisions about how to value the work they do. And it may be that they need to rethink how they organize research -- we might start, for example, by addressing the fact that pharmaceutical companies spend two to three times as much on marketing as they do on research."

The fight, it is clear, has only just begun.

Shares