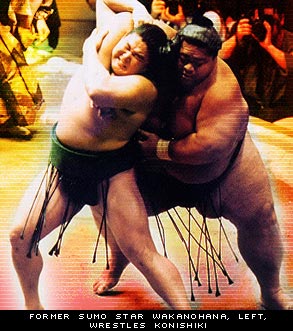

For 1,500 years, sumo enthralled Japan. Then, after a spate of high-profile retirements around 1985, something changed, and the ancient and sacrosanct tradition was marginalized. Grand finals were sidelined by sports more popular in the youth culture. Michael Jordan held more clout in the eyes of teenagers than those burly men in G-strings. Stadiums were half empty and television ratings plummeted to single digits. Then came Wakanohana.

He was Japan’s 66th yokozuna — sumo’s top rank — and he was an instant success. The fizzling sport suddenly had a media darling, popular and sexy. The tabloids obsessed over his antics, family fallouts spawned gossip frenzies and women went wild for his upbeat image and leaner figure. There was also the younger brother, Takanohana, equally celebrated, possibly more talented. Together they ignited the “Waka-Taka Boom.” It was understood that they would salvage sumo from creeping obscurity and reestablish it as a sport for the 21st century.

The Waka-Taka Boom was going to be the JSA’s revival. The plan was for the duo to generate just the right momentum to release sumo from the doldrums of irrelevance. Their image was popular among young people but didn’t offend the older constituents. Japan’s national sport was in the clear.

Wakanohana went professional at 17 and then endured four years of “hell” preparation under the tutelage of his father, a great sumo wrestler. The alarm rang at 3 a.m. and was followed by hours of “Rocky”-esque training. Sumo schools have no machines; trainees practice on barren earth patches under the guidance of despotic coaches who use a Draconian shinai — or bamboo sword — to poke and intimidate their charges into deeper squats and sharper slaps. Wakanohana’s tone drops when he talks about his trainer: “He is my father now, but then he was my coach. There was no room for bonding.”

Wakanohana took five Emperor Cups — the world championships of sumo wrestling. His style was often criticized, but it was unique. He had tremendous speed, great agility and unparalleled balance, a result of a seeming disadvantage — his small stature. By sumo standards he is almost a midget — during his prime he weighed a trim 302 pounds, which minimized the excess flab prevalent in some of his more beastly looking compatriots.

“This is my aesthetic,” he boasts. “I like the image of a small, strong man hurling a larger opponent across the ring like a torpedo.”

But Wakanohana soon learned there’s more to sumo than wrestling. The JSA has jurisdiction over every wrestler’s public activities — interviews, endorsements and public appearances must all be cleared. It became clear that Wakanohana was the wrong man to preserve anachronistic regulations. It seems he went too far in livening up sumo; he simply wouldn’t cooperate with the JSA.

“I was always a black sheep. Takanohana and I have always had our own ideas,” he admits. “I didn’t want to wrestle them, but it was never going to be a happy marriage.”

Indeed, what the duo set out to do was impossible, given sumo’s climate. Today the sport looks much like it always has. It’s rife with antiquated regulations and politically incorrect traditions: No women may enter the sacred sumo ring; no two wrestlers from the same training stable can fly in an airplane together; no wrestler is authorized to drive a car; and haircuts are forbidden. The rulebook is just about as hefty as a wrestler himself, and the famously oligarchic Kyokai, the Japan Sumo Association, refuses to budge. The JSA’s head, Katsuo Tokitsukaze, believes in the inveteracy of custom — even, it seems, if that costs his sport its fans.

Wakanohana’s brand of iconoclasm was more subtle than flagrant; he never fought for his views, but played along with the rules until they became inappropriate. Then he broke them.

“They said that I couldn’t drive my Ferrari — so I sold it,” he says. “They told my brother that he couldn’t marry his girlfriend [Japanese/Dutch model Rie Miyazawa] — so he didn’t. They told me that I couldn’t appear on television without their permission — so I didn’t. They said that my wife and children couldn’t attend my matches at the stadium — but I brought them anyway.”

It’s been a few months since his retirement from professional sumo wrestling, and Wakanohana, who now goes by his birth name Masaru Hanada, looks more Silicon Valley than Shinto sire. He has lost 62 pounds, the mandatory ponytail has been shorn into a fashionable red-tipped flattop and his Prada outfit is basic black. He laughs easily, but a deeper frustration resonates.

“They lost the Waka-Taka opportunity out of sheer stubbornness,” he says, adjusting his too-tight collar. “Really it came down to this: Our popularity could not translate into a better future for sumo because of them. Now I am free, and this feels much better.”

Wakanohana was born 30 years ago into sumo blue-blood royalty. His uncle is former sumo sensation Wakanohana I, an outspoken and controversial member of the sumo establishment. The brothers were both coached by their father, the former Ozeki Takanohana I, who now owns the successful Fujishima stable and goes by the name of Futagoyama Oyakata.

Wakanohana was reluctant even to join the tradition he ended up ruffling. “I never wanted to be a sumo wrestler,” he confesses. “This was never my idea.” As a child he knew he wanted fame, financial independence and sporting glory, but his image was of the grand-final playoff sort, not the sacred Shinto salt-throwing rituals of sumo. “Sport is supposed to be international, but I missed out on all of that.”

Mieko, his wife of six years, is now pregnant with their fourth child, but the family line of wrestling luminaries will likely end with him.

“Over my dead body will they get into sumo. My family has given enough to this sport and enough is enough,” Wakanohana almost spits. “I want them to swim or play tennis. Anything with an international flavor will be good.”

In fact, there are plenty of reasons to steer one’s children away from sumo. Early death in the professional circuit is tolerated as either inevitable or normal. “The competition out there is fierce,” Wakanohana laments. “Death is the end of life, but it is also the end of sumo.” While he concedes that obesity and the associated health complications do end lives early — 50 to 60 being the typical life span of a wrestler — he sees death as more integral to the philosophy of sumo.

“Wrestling is a martial art,” he explains, “which in its purest form is about killing. A lot of my training was learning about how to kill, learning about where the human weak points are.” With no invitation he elaborates: “Yes, I could kill you,” he only half jokes. “I could kill everyone in this room; 30 seconds apiece, but the law protects you.” He laughs. “Sumo is a mixture of boxing and judo. Each bout resembles a massive car accident — the force is more than anyone can imagine, and what’s more, it hurts like hell.”

The wrestlers on TV are the survivors. Few words are published about those who do not make it. Some die in training; others endure recurring injuries that force them into shameful and early retirement. Wakanohana can’t get sentimental; death cannot become a fear. “You often hear about trainees found floating in the bath after practice,” he remarks deadpan. “Their hearts stop beating — I have seen some bad stuff: Broken necks and protruding collarbones are common injuries.” His words sound harsh; there is none of the romanticizing many athletes use to describe what motivates them. “The most important thing is not to get spooked. You have to be strong and deny the danger.”

Critics suggest that his small stature and light body contributed to his long string of injuries and eventual defeats, but he sees it differently: “A lot of injuries occur today due to slack preparation and because wrestlers are carrying around too much bulk. My injuries came from my hard work.”

A problem thigh contributed to his final decision to retire — an unexpected announcement that scuttled the JSA’s agenda. The Waka-Taka Boom was over and the future of sumo again looked dire. “Eventually it became impossible,” he says. “The mental outlasted the physical, and my leg was just too sore.”

This “slack preparation” could also be the cause of a further ailment that is slowly poisoning sumo’s reputation. Yaocho, or bout fixing, is the practice of paying a fellow wrestler to lose. As all-important sumo rankings and incomes correspond directly with how many wins a wrestler can clock up over a season, yaocho can have a substantial and lasting effect on a wrestler’s career and earning capacity. In recent years, reports of yaocho have circulated more and more. Keisuke Itai publicly apologized for his own participation, and went further by pointing the finger at greats like Ozeki Chiyotaikai and the Hawaiian giant Akebono, who later denied any wrongdoing.

Neither Wakanohana nor his brother was ever implicated: “I never let my fans down,” he says. “They were my focus and I would never have abused their trust.” After Itai’s confession, right-wing extremists, infamous for bullying intrepid journalists and politicians who hazard the threats and continue to discuss some of the less divine aspects of Imperial Japan, exerted their moblike influence. “The black trucks visited many stables,” he claims, “but we were clean and we always have been. Nobody visited us.”

Four years before Itai dropped the bomb, his trainer, Onaruto Oyakata, and another insider, Seiichiro Hashimoto, went public with allegations linking sumo to the underworld, and claiming that yaocho had reached plague proportions. The JSA dismissed the accusations as “scurrilous lies,” but the plot thickened when later both informants died within hours of each other. Itai denied any foul play, but yaocho remains a concern.

Tokitsukaze remains obdurate. He denies the yaocho rumors and ignores the evidence. But his stonewall approach and lackluster reign have not gone unnoticed, and many of his recent decisions have generated a lot of negative publicity — the last thing sumo needs. Even his recent approval of 12 new winning techniques has failed to reverse growing resentment. Osaka’s female governor, Fusae Ota, has now been twice denied her entitlement, as governor of the city of Osaka, to bestow the annual Spring Grand Sumo Tournament trophy to the winner. Since 1953 the governor has always held this privilege, but the JSA deems it inappropriate for a woman to enter the ring, so Ota has been exiled to the stands.

Wakanohana, sumo savior himself, has now indicated his own sharp disappointment with many of the association’s decisions by taking the unprecedented move of quitting the association entirely. “I can’t say that I like where sumo is heading,” he says, “and I could no longer abide by their ways.”

Never in sumo’s 1,500-year history has a yokozuna ever snubbed the association and walked away. “Three others were fired,” he confirms, “but I am the only one who has ever quit.” He sees Makiko Uchidate — the JSA’s newest recruit — as a hopeful addition to an otherwise aging creed, but worries about the background of board members. “I think they need to include retired wrestlers, people who know what it’s really like out there. Most of the board is out of touch.”

Now Wakanohana is forging a new career as host of a primetime sports show — something the association would never have allowed. There are rumors of new sporting contracts: “I have done it before, which means I could do it again,” he says.

Sumo’s future is uncertain. It hinges on the JSA’s willingness to evolve. If current policies and dated doctrines continue, sumo’s support base could continue shrinking to a few curious tourists and the octogenarian die-hards. Unless the sport revamps its image, the next generation of wrestlers will not be fighting each other for trophies, but battling their distant samurai cousins for historical supremacy. Or perhaps they’ll just lead normal lives.

“Life is better than ever,” Wakanohana beams. “Tonight I am going to a Christina Aguilera concert, and tomorrow I’m free.”