It's a safe bet that the Spanish director Fernadno Trueba was able to make his new Latin jazz film "Calle 54" because of the success of "Buena Vista Social Club." But it's hard to imagine it will find the same audience.

Audiences responded to Wim Wenders' documentary because by the end of that film everything Wenders had shown you seemed all of a piece. The music fit not just the musicians, the personalities they showed both on- and offstage, but Cuba itself, the pace of life, the faded pastels and faded grandiosity of the battered buildings.

Toward the end, Wenders showed a wall painted with the slogan "THE REVOLUTION IS ETERNAL." The pleasure on the faces of these rediscovered musicians as they played told a far different story: Their music antedated Castro's revolution and now there was no doubt that it would outlive it. "Buena Vista Social Club" left you feeling like you'd been granted full entry to a world you didn't know -- the opposite of the condescension with which world-music fetishists often treat their discoveries, as though they were exhibits in a multicultural petting zoo.

"Calle 54" doesn't have that coherence or that vision. Alternating scruffily filmed introductions with performances set against crisp, vivid backgrounds, the movie is essentially a fan's scrapbook. Trueba began listening to Latin jazz in the '80s when a friend gave him an album by Paquito D'Rivera, the Cuban alto sax player. He was hooked and he speaks, in voiceover, of the enthusiasm he feels for the music and for the performers he's assembled.

Unfortunately none of his heartfelt declarations do much to transcend that enthusiasm. Trueba will tell you that so-and-so set a new standard for the genre by combining elements of flamenco or salsa. But since he tells you nothing about the origins of the music and doesn't give you a sense of what it sounded like in its initial form, we've got no way of judging how closely the performances here hew to tradition or make way for innovation. He's anxious to get to the music, and like someone playing a treasured record for a friend Trueba seems convinced that we'll fall in love too if we just listen.

I didn't want a musicology lecture, but when you go to a documentary about Latin jazz you hope to find out something about the music's beginning, how it grew, how it changed, if being born in the United States (as Tito Puente, and Jerry Gonzalez of the Fort Apache Band were) leads to a different approach than that taken by the musicians born in Latin countries (the other performers hail from Brazil, Argentina, the Dominican Republic and a preponderance from Cuba). Mostly, I wanted to know about something that I've noticed in my infrequent exposure to Latin music performances, which is that the music seems to transcend age barriers. (There was a great moment during an HBO concert given by the Latin pop star Marc Anthony when he brought out Tito Puente and the predominantly young audience at Madison Square Garden went nuts.)

I learned a lot more about the music in the few minutes it took me to read the liner notes that the Cuban novelist Guillermo Cabrera Infante provided for a 1994 album by the great mambo bassist Cachao (Israel López). Infante explains how the mambo grew out of the danzón, which, of all the damn things, originated in English country dancing, spread over Europe, to French Caribbean colonies and eventually to Cuba. (Infante even quotes George Eliot in "Adam Bede" on the glories of the country dance.)

That's a hell of a story, and a better one than you hear in "Calle 54," though you get the feeling that, had Trueba only probed a bit, the musicians might have come up with tales to match it. You want to know, for instance, why Andy González, who we see visiting the Bronx home where he grew up, is no longer playing with his brother Jerry in the Fort Apache Band. At one point we learn that the pianist Bebo Valdés left his wife and kids in the early '60s for a Swedish woman whom he is still with.

Later Bebo and his son, the flabbergasting pianist Chucho Valdés, meet for the first time in five years to play a duet. They're genuinely affectionate and at ease. (The slim elder Valdés greets his rotund son by saying, "You're fat as a toad.") But when you discover that Bebo has never met his grandchildren, you want some more about the dynamics of their relationship. The lackluster introductions Trueba has filmed are just marking time, filler tossed in to link the performances. (And when he does allot a performer some time to talk, as he does with Gato Barbieri, the tenor saxophonist, it's a mistake. Barbieri speaks of how the spirit that informed the movies and jazz of the '60s and '70s died off. True enough, but he speaks with the detachment of a hipster grandee.)

The best music movies put you inside the performances (as happens in "The Last Waltz" and "Stop Making Sense"). It doesn't happen here because Trueba is too awestruck by actually having assembled all his beloved musicians for the film. You can't hold that against him -- who wouldn't be at least a little awestruck in the presence of his idols?

The professionalism of the way in which he and cinematographer Jose Luis López-Linares shoot the performers doesn't provide intimacy but the polish bespeaks a desire to show them off. (It's a little like the spiffy way in which Frank Tashlin shot the rock 'n' roll numbers in "The Girl Can't Help It.") Trueba doesn't especially have a lot of imagination. He decides to shoot the bandleader Chico O'Farrill in black and white to approximate big-band nostalgia. But he can't match the silvery black and white of the period he's trying to emulate and his camera movement and editing are anachronistically modern.

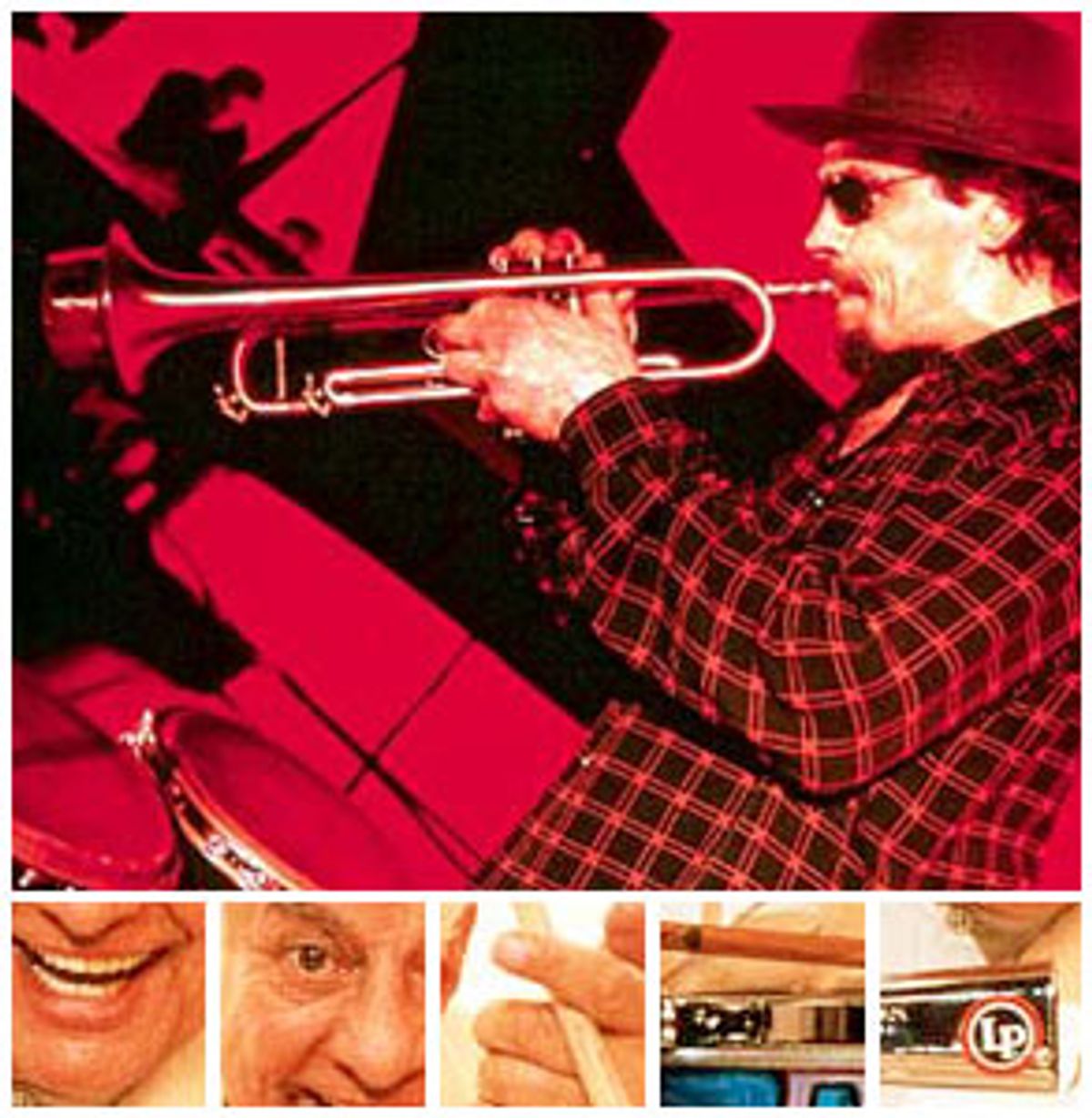

Probably everyone who sees "Calle 54" will feel there are performances they can leave or take. For me, the former includes the loungey piano tinklings of Eliane Elias and the pretensions of Gato Barbieri. I warmed up to fluegelhornist Jerry Gonzalez and the Fort Apache Band as their performance progressed, partly because Gonzalez, hiding behind dark shades and hat, has a hipster prankishness. Try to imagine Carlos Santana possessed by the soul of Top Cat and you've got an idea of what he looks like.

The movie was blessed with the luck to get what is probably the last filmed performance by Tito Puente. He mugs for the camera while playing timbales and vibraphone, popping his eyes, sticking out his tongue like a kid concentrating, circling his head with his mallets looking like a magician waving a wand and then wiping the sweat off his brow as he pulls off yet another trick.

The highlight of "Calle 54" is unquestionably the meeting between two Cuban greats who had never played together before, Cacho and Bebo Valdés (whose tapering fingers must be the longest of any musician's since Eubie Blake). The encounter has a casual mastery, a camaraderie that is created when one great musician finds a partner who exists on his level. (It's no wonder Trueba breaks the form of the film to show us the crew bursting into applause.) The later encounter between Valdés and his son Chucho is moving for another reason; it's the sweetest of competitions, each using his keyboard to lay down a series of loving challenges.

As great as those moments are -- and yes, they're worth seeing the whole movie for -- nothing got to me quite like Chucho Valdés' solo number. A large man possessed of an enormous gravity that seems to come more from his hangdog eyes than from his size, Valdés' style of playing is like nothing I've ever heard, encompassing both fluid, lyrical runs and abrupt staccato passages whose lightning-quick executions recall Bud Powell. But there's a serenity to Valdes that the tortured Powell never possessed. And key to it all is the lightness of the whole performance. It's as if you're hearing an age-old passion blown like a kiss across the room.

Shares