In every link on the food chain of life -- from grade school to college -- there was always one tall, skinny black kid who had it goin' on. All the chicks, black and white, wanted to get with him, and all the guys, black and white, tried to hang with him. In some instances, he shot hoops for the local team, but not always. He could crack up a classroom, teacher included, with one well-timed remark, but mostly he just sat in the back of the class and chilled, occasionally napping behind a dark pair of specs. Unlike the rest of us, he didn't attempt to be cool, he was cool. Damn if he wasn't born that way.

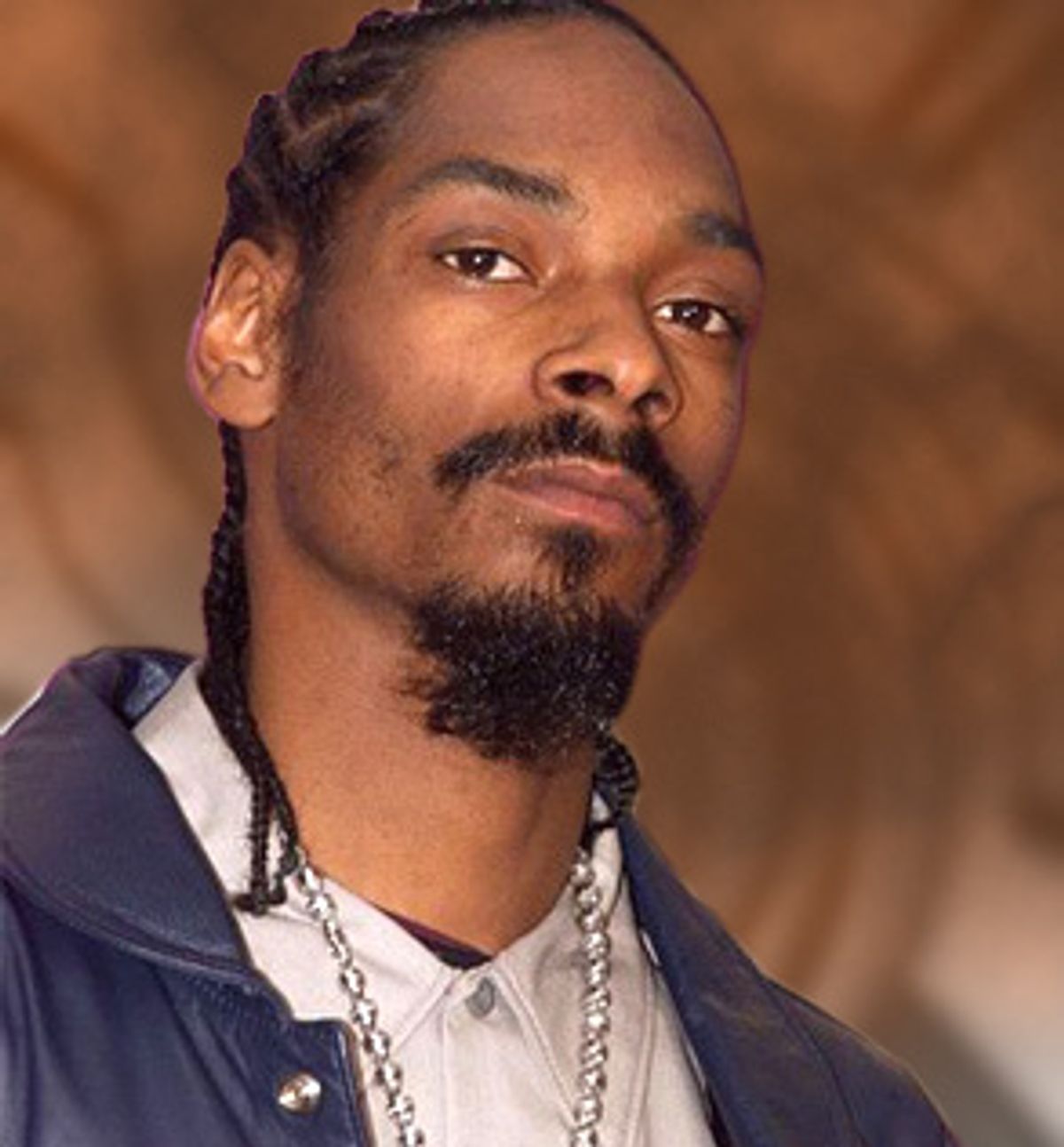

Snoop Dogg is that cat to the nth degree. The braided and goateed favorite son of Long Beach, Calif., popularly known as "tha L-B-C," has dominated the rap music dojo from his days bangin' with Dr. Dre on the 1992 bomb "The Chronic" to his own chart toppers like "Doggystyle" and "No Limit Top Dogg" and his latest ghetto classic, "Tha Last Meal." He was birthed on Oct. 20, 1971, under the dog star of G-dom. And long before he was helping to define, along with Dre, Ice Cube and others, that style popularly known as "West Coast" or "gangsta" rap, little Calvin Broadus was nicknamed "Snoop" by his parents, who thought he looked like Charlie Brown's hipper-than-thou beagle.

From jump, Snoop had a sobriquet most kids would kill for. Sure, a name like Snoop doesn't make a career, but it is definitely an asset. So is the sort of effortless charisma Snoop has, not to mention his inimitable rap "flow," that verbal dexterity, sharpened by the streets and a stint in the Los Angeles County pen for hustling crack when he was barely out of high school. As with any personification of the laid-back, blunt-smoking L.A. steelo, a gang-star's rep is bolstered by an aura of menace. Though Snoop has never had the urgent, in-your-face thuggishness of his colleagues, he has made no secret of his association with L.A.'s oldest black criminal enterprise, the Crips (hence his fondness for blue). He beat the rap for murder in 1996 when a jury found him not guilty in the 1993 shooting death of one Philip Woldermariam by Snoop's bodyguard McKinley Lee (when Woldermariam, for reasons still unclear, came gunning for Snoop). There's his beef with former employer and Death Row titan Marion "Suge" Knight, which has been going on ever since Snoop ditched Death Row for Master P's No Limit in 1998. And on a yearly basis, it seems like the po-po snag Snoop or someone in his employ with weed.

Like rock stars back in the day, members of rap's crème de la crème are expected to be rule breakers, badasses and so on. They're supposed to be outlaws, anti-authoritarian figures, getting away with murder and just about everything else to be, in the words of one of Snoop's most famous lyrics from the "Doggystyle" album, "rollin' down the street smokin' Indo, sippin' on gin and juice/Laid back -- with my mind on my money and my money on my mind."

Think of the Dionysian revelry of rockers like Mick Jagger or David Bowie -- perhaps Bowie more than Jagger, since the Thin White Duke was like an ivory-hewn precursor of Snoop -- and you begin to get a sense of what Snoop's appeal is to the masses. Snoop himself broke it down in this passage from his 1999 autobiography "Tha Doggfather":

Maybe you're holding down a nine-to-five, paying out on a second mortgage, with child support, alimony, car payments ... all that shit. Maybe your life was locked down, set to unroll all by itself, right on schedule from cradle to grave. Maybe it was all safe and secure and settled from the minute you popped out and they put your name on a plastic bracelet around your wrist.And maybe that shit is getting old. You might look around and ask yourself, "Is this all there is?" and then you hear one of my songs on the radio or catch a video on MTV and suddenly it all starts looking larger than life -- your sorry life anyway. In Snoop Dogg's world, the bad guys are badder, the good guys are gooder, the scrilla is fatter, and the women are finer than you've ever seen. But most of all, in my world, you can read the rules. You know who your friends are. You can spot your enemies a mile away. Life is more precious because death can be waiting around any corner, at any time.

This attitude recalls an artistic tradition far older than rap. It stretches back to the Marquis de Sade, Rimbaud and Verlaine and, even further, to Euripides' play "The Bacchae," where the god of wine and women sets himself against the very foundations of society -- and wins. I doubt that Snoop has read Rabelais, Céline or Huysmans, but the triumph of decadence over the skull-numbing boredom of the status quo is one of the most powerful themes in the history of art and literature.

I can hear the lit-crit know-it-alls snorting their disapproval. But undeniably, above the wigger-kid brio of Eminem, or the now-passé goth sociopathic sensibilities of Marilyn Manson, and towering over the insignificant sputterings of what masquerades as literature these days, Snoop Dogg is a one-man threat to society's established order. With Bush in the White House and riots in the streets of Cincinnati over yet another cop killing of an African-American youth, what could possibly be more of a menace to authority than an immensely wealthy black man spitting phrases like "cuz it's 1-8-7 on an undercover cop" (that number being cop code for murder) or blowing chronic smoke into the faces of our drug czars?

Like it or not, for those who believe the system's jury-rigged against them, Snoop's music is real and, in the case of those from the 'hood or in lockdown, representative of their experiences. Snoop Dogg put Long Beach on the map, introduced chronic to the national consciousness and raps with authenticity about life in the ghetto, on the corner and behind bars. Snoop is rap's answer to '70s zeitgeist Richard Pryor, who gave his comedy albums titles like "Bicentennial Nigger" and did bits comparing the sexual skills of black and white women. One might long for some overtly political rhymes, but as Snoop suggested in his book, rap is itself a sort of cultural rebellion:

Rap talks about the way things are, not just the way things ought to be. Like back in the sixties, when they had protest music, those songs gave people a clue about what was really going down around them, got them motivated. Rap has got some of the same purpose, but it's about a whole lot more than complaining over the situation. Rap is an answer in itself, a way for the niggers to make a noise, get noticed and scare the shit out of a lot of motherfuckers who've been trying to pretend that, if they don't pay us any attention, maybe we'd just go away.

Indeed, though criticism of violence in rap lyrics is widespread, the lyrics of country and western songs -- usually about divorce, drunken driving and adultery -- and of rock, which was dangerous a long time ago, before most rock stars turned 50 and had their first face-lifts, rarely receive the same scrutiny. Also, the artists in country and western and rock are usually as white as rice, suggesting the double standard that's involved when a black man speaks his mind.

Full disclosure: I write this as a cracker with no use for the powers that be. On that level, I connect with Snoop and other rappers whose disgust with society's enforcers is self-evident. Almost every night when you turn on the tube, you see someone like Joe Lieberman, Bill O'Reilly, Rudy Giuliani or Rush Limbaugh, whose primary agenda seems to be to tell all of the rest of us what we can and cannot do. Unless you're a talking head yourself, counteracting them seems impossible.

So when Snoop pops up in a music video on BET, cruising in a lowrider, marijuana smoke curling out of his mouth, or when I hear him on the radio singing about "Hennessey 'n' Buddah" or about "stackin' dollars," "layin' a girl on her back" and smokin' "till your eyes get cataracts," it makes me wanna holler. And when I see that he's teamed up with my other hero, Larry Flynt, to put out the first ever rap-porn collaborative effort, "Snoop Dogg's Doggystyle," I know that freedom rings in at least one part of this nation, no matter how much institutions of repression like, well, the Federal Trade Commission, the Drug Enforcement Administration and the U.S. Senate wish otherwise.

It's no mistake that Snoop's music recalls the more egalitarian decade of the '70s, an era when "Soul Train" was all the rage and every Saturday morning brought us "Schoolhouse Rock" and "Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids." Musically, Snoop's raps bounce, incorporating elements of soul and funk, sampling Earth, Wind and Fire and sounding for all the world like a latter-day version of Kool and the Gang or the Commodores. Snoop's mom remembered in an MTV interview that she and Snoop used to party on Fridays and Saturdays, drinking a beer or two and listening to the platters that mattered then. And Snoop has made the connection quite clear in several interviews.

"Growing up, that shit's all we heard," Snoop told Playboy in 1995. "Al Green and Curtis Mayfield. I'm into the soul collection. That's inspiration to me. Dramatics. Teddy Pendergrass. Isley Brothers. Enchantments. That's why motherfuckers say I sing instead of rap. That's why I got more of an R&B sound. They say my shit is gangsta because of the words I use. But if you listen to it, it's R&B shit."

The 1970s echo throughout Snoop hits like "Lodi Dodi," "Snoopafella," "Murder Was the Case," "Nuthin' but a G Thang" or "Snoop Dogg, What's My Name, Pt. 2?" And Snoop often mimics the great black DJs of that time with segments throughout all of his recordings that sound like they've been lifted from the radio. (Snoop has even had his own radio show, on and off, on L.A. rap station Power 106 and others.) If Snoop's language is harsher than we were used to back in the days of "Good Times," Jimmy Carter and the smiley-face logo, well, the times have become harsher too. Only Bill Clinton's presidency broke the tide of racial hostility in this country. Now that he's gone, we can look forward to the cruel cynicism inherent in every Republican administration.

As Snoop told Playboy: "The media created the buzz of rap being so terrible, but terrible is the ghetto shit we rap about. We put it in their faces. Motherfuckers losing their lives. The fucked-up system. They don't want to hear it."

They sure don't, Snoop. In fact, if you listen to some, they seem most afraid that blacks in this country may stand up and demand reparations for generations of slavery. But Snoop & Co. are not asking for shit, they're taking the dolo fair and square, much of it from the pockets of young white kids who love the beats and the attitude. It's a phenomenon Snoop wonders at as much as anyone, staring at a sea of Caucasian faces in places like Oslo, Norway, or Copenhagen, Denmark, as he states in "Tha Doggfather":

Looking out at those happy white people, bumping to the beat, flashing signs and singing along to my words, I have to ask myself, What are they getting out of all this? How is it they can relate to hip-hop as strong as anybody as black as I am? What's the connection? The answer comes around to being real. It doesn't matter what color you are -- anything that's got the ring of truth, you got to deal with one way or the other ... So I just tell the truth and let the rest of you motherfuckers sort it out for yourselves.

I'd back up Snoop against Dick Cheney, Asa Hutchinson and whatever other palefaced ersatz brownshirt they wanna throw up. It's not like Snoop really has to try to be a playa. It's in the man's blood. As he drops on the hit "Bitch Please," "If I don't move, a nigga like me? I don't lose./But you know me. Dog, I'm movin'./Ain't nothin' to it, but to get to groovin'."

Shares