It was a strange and a sorry sight. As a spokesman for Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, Richard Boucher had spent months defending the liberal policies of the Clinton administration on family planning, arms control and the environment. But as he broke in the new "Star Trek"-like briefing room at the State Department's headquarters in Foggy Bottom a few weeks ago, he was forced to recant. Like Galileo, who was forced to say the sun revolved around the Earth, Boucher said what those in power wished him to say.

On his first day in President Bush's new administration, Boucher had to shift 180 degrees from the Clinton policy he and others had worked on for eight years to help hundreds of millions of people seeking to control their family size. Now Boucher had to defend the Reagan-era Mexico City rules on family planning, newly restored by Bush, which bar U.S. aid to overseas organizations that discuss or counsel on abortion with their clients, or lobby to remove bans on abortion.

Like Boucher, scores of Foreign Service staffers have had to reverse course on a dime. In the nonproliferation bureau, staffers worked for eight years for a Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, but the Bush administration and the Republican-controlled Congress declared open season on that agreement. "A lot of people are disheartened because the people in this administration don't really believe in the mission," said one State Department official, speaking on condition of anonymity.

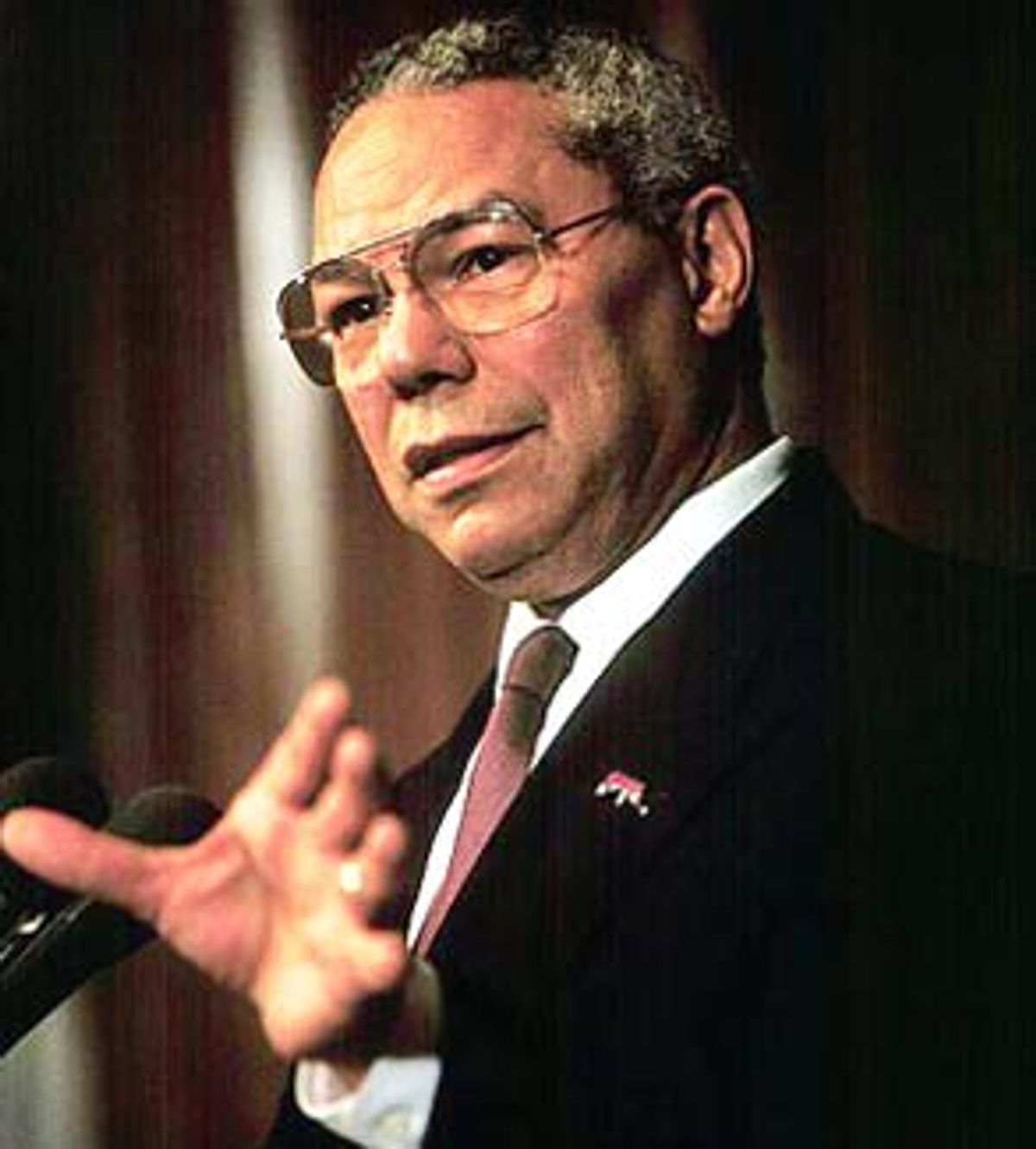

But State Department officials are hired to carry out policy, even when that means mouthing new party lines. And that policy is decreed from on high, higher even than the seventh-floor office of Secretary of State Colin Powell. Even he admitted that he was against the Mexico City rules. (In his autobiography and elsewhere he has said he favors abortion rights.) But just as Powell is a good soldier carrying out the orders of his boss, so are Boucher and everyone else at State required to go along with the policies of the new administration.

Yet despite this jerk in foreign policy by the new administration, one thing has changed drastically for the better at State -- under Powell, morale has increased dramatically. Since he took over, say many at State, the closed-door snobbery that prevailed under Albright has given way to a feeling that the leadership is open to the views and expertise of its staff, and is no longer a closed group of people shut off from Foreign Service professionals.

The biggest boost to State morale has been Powell's own personality and style, especially his pledge to rely on the rank-and-file experts in the department for higher-profile roles, rather than simply the anonymous drafting of papers that bigwigs deliver at hearings and conferences.

Many cite the briefing on Mexico policy given to President Bush before his trip to Mexican President Vicente Fox's ranch -- it was delivered by the desk officer for the country, a humble toiler in the department who probably knows more about his assigned country than the assistant secretaries who as a rule get to make speeches and negotiate. Desk officers also briefed Powell prior to his Balkans trip last month.

It's too soon to tell, say most officials, if the consultations with lower-level staffers will continue and if morale will remain high, given all the disappointments State Department staffers are having to endure.

Some officials got a fresh slap in the face earlier this month when the Senate confirmed the new arms control czar, John Bolton, a staunch conservative who railed from the sidelines against arms control treaties and the United Nations throughout the previous eight years. Bolton complained to a congressional panel in September 2000 that the Clinton administration pursued "assertive multilateralism" from its very first days right through to its closing moments. "The risks and pitfalls for the United States, and indeed for the United Nations itself, in pursuing these flawed and potentially dangerous policies have rightly attracted extensive congressional attention during the Clinton administration."

Arms control treaties depend on multilateral understandings. Thus Bolton's selection to run arms control at State seems a lot like putting the fox in charge of the henhouse to many at the department who have worked for years on limiting deployment of nuclear and conventional weapons. (Previous arms control director John Holum was seen as a true believer in treaties and inspection regimes to limit weapons around the world.)

In the environment bureau, some staffers are aghast at the sharp change of course on global warming. They worked for years on a treaty to limit emissions of carbon gases that are believed to cause global warming. Then came Bush's suggestion that the jury's still out on whether those gases are to blame.

It took only a few weeks for that line to drown in worldwide ridicule. But Bush has adamantly opposed the Kyoto treaty on controlling carbon emissions that was signed by the Clinton administration. Bush insists the treaty is unfair because it calls on the United States, the biggest emitter of carbon gases, and other developed countries to bear the brunt of rolling back their future emissions to 1990 levels. But it leaves India, China, Brazil and other developing nations free to pollute until they achieve higher income levels. The treaty now sits hopelessly in the Senate, where ratification is all but impossible.

After the hugely negative reaction to the Bush's early environmental declarations, he has tried to recant on some policies and sound a bit more protective of the environment. But environmental experts at State fear they may be reduced to developing arguments that sustain the Bush conclusions, which are based on scientific research done by a small segment of scientists and economists, often funded by large polluters such as electric, mining and industrial companies.

Their disappointment is matched by that of those on the State Department's Korea desk. Their years of careful negotiations had calmed down the hermit kingdom, led to a summit with South Korea and won a nuclear weapons development freeze and a missile moratorium. Last month when Bush kicked the legs out from under negotiations with North Korea and canceled missile talks, folks at the Korea desk were thirsty for stiff drinks after work.

U.S. negotiators such as former diplomat Robert Gallucci, now dean at Georgetown's School of Foreign Service, had patiently sat through diatribes and threats from North Korea until they won the confidence of the isolated former enemy. North Korea turned off its only nuclear plant in 1994 and shut down its plutonium reprocessing facility in return for promises of U.S. heating oil and twin nuclear power plants to be paid for by South Korea and Japan. Gallucci said he was aghast at the decision to stiff-arm the North. And this just as South Korea's President Kim Dae-Jung was in Washington. Although Bush and Powell voiced support for Kim's "Sunshine Policy" of friendship toward the North, they deeply humiliated Kim by slamming the door on talks with Pyongyang.

Sources inside the State Department indicate that Bush's review is moving in the direction of endorsing the Nuclear Framework Accord of 1994, which really began opening up North Korea to America and the West. They expect that policy will ultimately be continued, as will many other Clinton-era policies. And even the North Koreans appear to be taking the change in stride. After a few shrill outbursts against U.S. hegemonism after the Bush pullback from talks, leader Kim Jong Il announced he'll continue his moratorium on long-range missile tests for two more years. But for those who spent nearly a decade prying the North Koreans into the world, the new policy was a roller coaster ride without seat belts.

In fairness, woes at the State Department didn't begin with Bush. Some of the worst attacks on the department's morale began in 1994, when conservatives won a majority in Congress for the first time in decades. They proceeded to launch verbal potshots at the "striped pants" snobs at State, suggesting they be forced to give up their fancy French cuisine for ordinary American food. Sen. Jesse Helms, R-N.C., has been the influential chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee since 1994 and a constant antagonist of diplomatic efforts, seeking to slash foreign aid, withhold United Nations dues and collapse agencies within the department.

In a way, the charges of snobbery weren't entirely unfounded, though they might have been misdirected. "The last part of the Clinton administration had very little appreciation of the service or the needs of the professional diplomatic service," said Marshall Adair, president of the American Foreign Service Association. Other Foreign Service officials spoke of a "cabal" at State under Albright, a closed group that did not want to hear views that differed from their own. One recalled that anyone who voiced criticism of policy -- no matter how deep his understanding and experience in an area such as the Balkans or Asia -- was likely to be frozen out of future deliberations, or even have his career sidetracked.

By contrast, former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Richard Holbrooke was remembered as a senior diplomat who would yell at anyone criticizing policy but then, if the criticism was well-founded, take it to heart and possibly adopt it. At least, said the source, speaking on condition of anonymity, Holbrooke did not harbor grudges against those who disagreed with him.

But Powell goes further, relying on the professional staff, and that has meant a lot to people at State. In his first few months there he has made Foreign Service professionals the core of his management. When his plane stopped in Israel for his talks with leaders there in March, Powell took out 20 minutes to speak to the assembled staff of the U.S. Embassy in Tel Aviv at the airport. One U.S. diplomat said, to no one in particular, "I never saw anything like this." Another said that she had never before shaken the hand of the chief of the State Department in a 20-year career. And Powell's remarks were a pep talk, praising the diplomats for serving in dangerous times and being the front lines of U.S. foreign policy.

Adair and others say that Powell's background as a military commander makes him realize that morale is critical to the mission and so he does what he can to massage the feelings of the Foreign Service. "Powell also gives no indication he feels uncomfortable with the Foreign Service or uncomfortable with people who know more than he does."

Another reason Powell has won hearts in the department is because he has fought to increase the foreign affairs budget by 5.5 percent, most of which would go to the State Department. The proposal is currently running the congressional gantlet of subcommittees and floor votes. The low point for the State Department's funding actually came during the Clinton administration, when the budget was so lean that hiring was halted for two years. Now there's a shortage of 300 midlevel Foreign Service officers and 700 additional slots remain unfilled, said Adair.

Powell's positiveness notwithstanding, for a very small number of diplomats, radical changes in policy may be a reason to cash in their chips and seek another job. It's not unheard of even for bureaucratic functionaries to resign over conflicting views. Four State Department officials walked out over the Clinton administration's failure to intervene early on in the Bosnian civil war.

So far, says Adair, there hasn't been any such nobility (or zealotry). Most Foreign Service professionals rely on their thoughts rather than their feelings, according to personality tests, says Adair -- himself one of the 2 percent who score higher on feelings. "Most of us have gone through such changes before." And even if the direction appears to go from cherishing every rosebud and snail darter in one administration to "harvesting" the planet in the next, people at the State Department know that little may really change once policy tackles reality.

For example, if the Mexico City policy does bar U.S. foreign aid from going through Planned Parenthood and similar groups that counsel or lobby on abortion, other groups will likely take up the slack and distribute condoms and other aid.

But the harsh forecast is that most of the large family planning outfits capable of delivering large-scale help will fail the test of the Mexico City rules, which require proof that doctors and nurses are not -- even in private -- discussing the option to obtain a safe abortion with women who have unwanted pregnancies. That means countries that need to build condom factories or birth control clinics will not be able to do so with help from the U.S. This "gag rule" has halted a lot of family planning aid and left some diplomats and foreign aid experts at State frustrated.

However individual policies manifest on the ground, a larger question that will face toilers in the State Department is: Who is running the foreign policy process? Is it liberal Republican Powell? Or the more hawkish trio of Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, Vice President Dick Cheney and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice?

Shares