As Colin Powell swept across sub-Saharan Africa last week, he delighted leaders with the attention of the Bush administration but shocked the continent with calls for the "big men" who cling to power at all costs to step aside.

As the first African-American secretary of state, Powell has been accorded near-messianic treatment in Africa. And perhaps because he is black, there was a profound resonance to Powell's harsh criticism of the doddering strongmen ruling Zimbabwe, Kenya, Gabon, Togo and other countries, and his call for democracy and governments that are accountable to their people.

On the plane from Washington to Mali, Powell admitted to reporters that he felt an "emotional twinge" in returning to Africa. He had visited several years prior to being named secretary of state. "Obviously I'm moved by the fact that I'm the first African-American secretary of state to visit Africa," he said. He reminded reporters that his job was to represent the Bush administration and "show we have an interest in Africa."

People know this. But despite some critics (including a handful of pro-Palestinian demonstrators who blocked his car at a university in Johannesburg, South Africa), crowds across the continent greeted Powell with a hero's welcome. As we traveled from site to site, local people told him of the pride they felt in him, and the hope he brought as a black leader. One close aide said that he was sure Powell felt a powerful connection, as did those who meet him.

What is surprising and perhaps refreshing for Africa, with its "big men" and slavish respect for authority, is that Powell is American to his core in his commitment to accountability and rule of law.

"There are many who seem reluctant to submit to the rule of law and the will of the people," Powell said Thursday at Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg.

"After more than 20 years in power, Zimbabwean President [Robert] Mugabe seems determined to remain in power. As you know, it is for the citizens of Zimbabwe to choose their leader in a free and fair election." Mugabe's supporters have intimidated and harassed opposition politicians, journalists and white farmers in a bid to whip up support for another term in power. Following Powell's speech, Zimbabwe officials promptly told the U.S. to butt out of their domestic affairs.

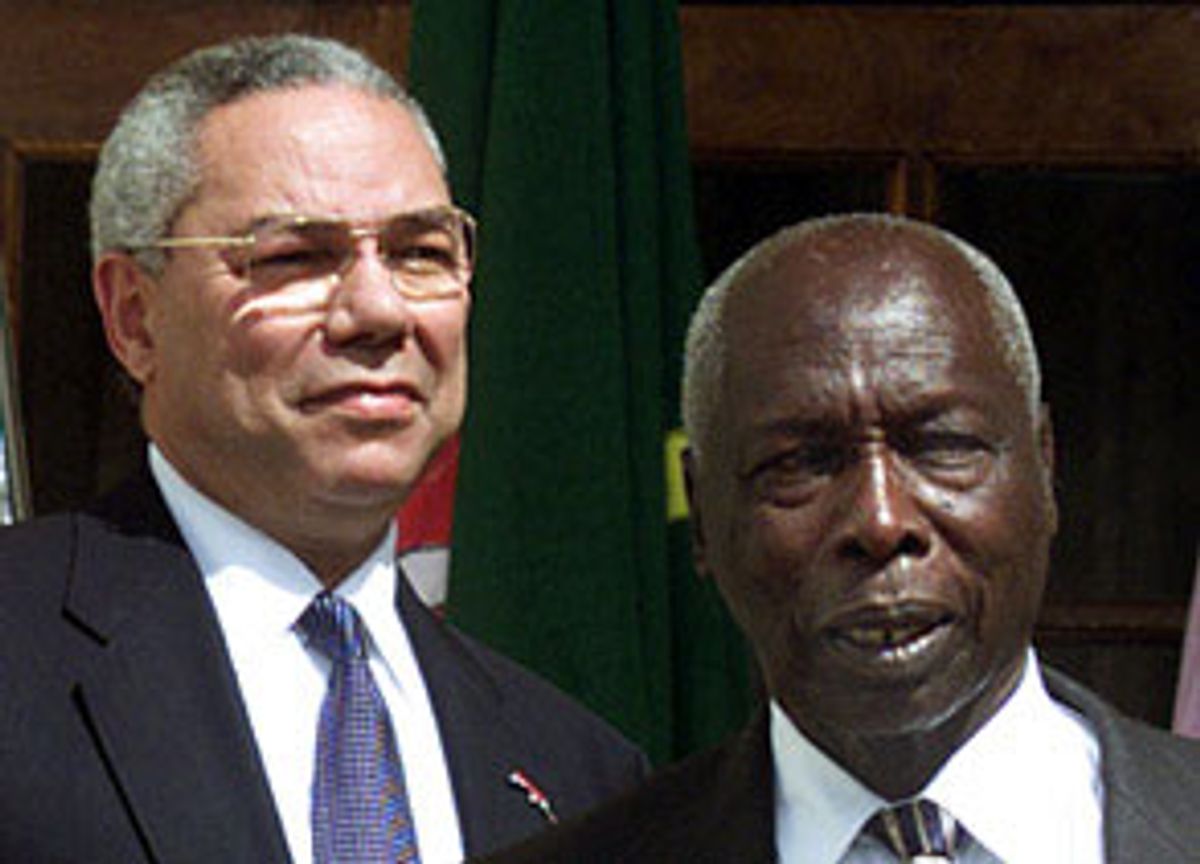

In Kenya, President Daniel arap Moi also has clung to power -- for 22 years -- and in Nairobi on Saturday, Powell learned that the cagey, aging politician may well try to run again next year, despite a limit of two terms under the nation's 1992 constitution. Moi supports a commission that is rewriting the constitution and will probably do so in a way that will allow him to run once more.

I asked Moi at a press conference, after he met with Powell, if he would heed the American secretary of state's call and unequivocally say that he would not stand for another term in power in next year's elections.

The Kenyan leader was silent for half a minute, glaring at the reporters across from him. "I think it is too much for foreigners to try to underestimate the intelligence of the African people," he said. "Those who will decide the destiny of Kenya, for instance, of other countries, will be the people themselves. I made my point when I was in the U.S. so I don't know what is worrying you." Then he turned and walked away.

A moment later a Kenyan journalist said to me, "everybody in this town knows he is going to run. He can't give up power."

The next morning, in Kibera, Nairobi's worst slum, 18-year-old Godfrey Oketch read the front pages of the newspapers he could not afford to buy. The headline of the People on Sunday read: "U.S. Expects Moi's Retirement in 2002." The paper read a bit more into Powell's support for democracy than the secretary actually said. But Oketch, one of hundreds of thousands living in Kibera's fetid, dusty alleys, said Powell's visit and calls for new leadership gave him hope.

"Colin Powell's visit has to make a change -- Moi has to go," said the young man.

"I hope the U.S. will pressure Moi to go. He has ruled for so long. People are tired and just can't wait for a change. He has failed. He has done nothing for this slum. The housing should be made well. The roads are bad. There is no water, not enough schools, not even electricity."

And there is AIDS. Most of the world's AIDS cases are in sub-Saharan Africa, and most of those cases go untreated, while the number of HIV-positive people is increasing by 15 percent each year.

One of the goals of Powell's trip was to push African heads of state to come out and openly declare AIDS a crisis caused by sex that requires self-control, condoms, abstinence and monogamy to be defeated. Leaders in Senegal and Uganda have done so, and seen infection rates decline.

But Powell was partially rebuffed by South African President Thabo Mbeki, who gave no indication after their meeting in Pretoria that AIDS was a big issue. Mbeki has even said that HIV may not cause AIDS, that poverty is the cause, and he has refused to provide anti-AIDS drugs to his people, despite the fact that about 25 percent of South Africa's sexually active people are HIV positive. The graveyards are rapidly overflowing and food production is being disrupted because so many farmers have died.

In Nairobi, at an AIDS center on the edge of the slum, Powell attended an AIDS awareness demonstration by young girls acting out ways to resist having unprotected sex. Outside the center, the teeming Kenyan poor circulated along muddy roads pitted with sewage. Many still have unprotected sex because they are unconvinced they are vulnerable to HIV infection.

Powell sang and danced with HIV-positive men, women and children, as he did in every other capital he visited, sharing touching moments with those suffering from the disease.

Agnes Nyamayarwe, 49, told Powell and his wife, Alma, that she has had HIV/AIDS for nine years and watched her husband and 6-year-old son die of the disease, lacking the costly anti-retroviral medicines that might have kept them alive. "It was difficult to see the young boy die," she said, weeping. "Instead of giving my children life, I gave them HIV. I live with the guilt that I infected my own child." Her surviving daughter is attending a university with help from U.S. funds.

Powell met another HIV-positive woman in Soweto, outside Johannesburg, South Africa. Florence Ngobeni said when her child got sick, her in-laws blamed her and didn't even tell her when her child died. "They said I didn't deserve to go to his funeral."

She told Powell of her hopes that, as a black American, he will change things for the continent. "I see you as a role model to the men in South Africa," said Ngobeni. "You have come to show us the light even though you have not brought us anything, as the media said. Your visit means a lot to us."

But some who work on the AIDS crisis in Africa say that to really make a difference, the administration must help public health agencies get drugs to those infected. "It's easy for Colin Powell to come around and listen to everyone singing and dancing, but it's another thing to do something," said Samantha Bolton of Doctors Without Borders.

At a clinic in Nairobi, Bolton described the ongoing fight to get low-cost AIDS drugs. "Only one or two thousand people get treatment but millions have HIV in Kenya." Drug firms meanwhile are fighting to keep control over their patents and are pushing for laws in Kenya and other countries that will bar generics or other copies. Bolton said that the Bush administration won campaign contributions from pharmaceutical firms, and she believes those firms are putting pressure on the U.S. government to protect their African markets -- even though Africa accounts for only 1 percent of their sales.

In a breakthrough development recently, drug companies dropped a suit against the government of South Africa. But even if the drugs become more available and affordable, AIDS experts say a responsible and complex healthcare delivery system must be set up to administer the drugs. If used improperly, the drugs could create drug-resistant forms of AIDS, gravely worsening the epidemic. According to Dr. Nils Daulaire of the Global Health Council, drug-resistant AIDS mutations are already appearing in America.

With his attention to the AIDS crisis, and to the continent's wars and fledgling democracies, Powell aims to build up Africa in the eyes of the Bush administration. Some speculate that the attention being paid to Africa is a sign that Bush is courting the 90 percent of the African-American vote he lost in November. Others say that Powell's visit occurred in spite of opposition by Bush officials who feel Africa is a sideshow of no vital interest to the United States.

"While Africa may be important," Bush said during a campaign debate, "it doesn't fit into the national strategic interests, as far as I can see them."

But as president, Bush has changed his tune, meeting with African heads of state and apparently giving the green light for Powell to strike out on his high-profile visit to the continent. Bush also found $200 million to pledge to a global health fund to fight AIDS -- small compared to U.N. estimates that $7 billion to $10 billion is needed, but more than any other country has offered.

Powell upped the ante with $50 million Sunday to fight AIDS and help some of the 1.7 million Ugandan orphans of parents who have died of AIDS.

Powell also came to help resolve three civil wars. In Mali he discussed with President Alpha Konare the Sierra Leone-Liberia-Guinea conflict and pledged to continue training Malian peacekeeping troops. In Kenya, Powell set up a meeting this week between the top U.S. aid official and the two sides in the Sudan civil war, the mainly Christian Sudan People's Liberation Front and the ambassador to Kenya of the Islamic government in Khartoum. Powell also extended a humanitarian hand by promising 40,000 tons of food to the Islamic north to fight famine. And in Uganda, Powell won a pledge by President Yoweri Museveni Sunday to withdraw most of the 8,000 Ugandan troops in the Congo, where a civil war has drawn in half a dozen nations greedy for diamonds, minerals and chunks of territory.

Throughout Powell's trip, his message was tough love. As a man of color, he has brought a tremendous breath of fresh air to the African continent. He has heightened the expectations that Africans have from their leaders -- whether it be to honestly lead them out of the horrible catastrophe of AIDS or to begin the path of development that was held out as a promise in the 1960s when independence removed colonial rule.

"If you take a look around," he said at Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg, " the most successful countries are those where the militaries understand their subordinate role under civilians in a democratic society -- where governments do not oppose peaceful opposition ... where journalists exercise their right to free expression ... where big men do not define foreign investment as depositing stolen billions in foreign banks and where ... frequent elections allow people to change their minds every few years as to the manner in which they will be governed.

"Nations making progress towards freedom will find that America is their friend," he added.

This story has been corrected.

Shares