It's a springtime Saturday afternoon, but the sunshine doesn't intrude on the scene in the New Brightness Performance Hall. Originally a huge storage space in a mall built in the early 1990s on the outskirts of town, the hall is now filled with some 300 young music fans, listening intently with cheap cigarettes clenched in their jaws.

The singer onstage is tall and emaciated, with dyed-red hair curling around his protruding cheekbones and slinky shirt unbuttoned to reveal a bony chest; he may look the picture of heroin chic, but his real drug is a reputed 10 hours a day spent in the pale green glow of a computer screen.

When he starts to growl into the mike, the crowd goes wild. Young men, just out of college and fleeing the conformity of their weekday white-collar grind, headbang in their Kurt Cobain T-shirts while rival rockers sporting the image of Che Guevara across their chests coolly nod in approval. A gaggle of female art students jingles gaudy imitation Tibetan jewelry, trademark du jour of China's budding bohemians, in rhythm to the music. A few of their less reserved sisters periodically toss undergarments at the stage.

The free concert was hastily organized only a few days before, and most in the audience give the same answer as to how they found out about it: "Yeah, I heard about it on the rock BBS too. So ... what's your alias?"

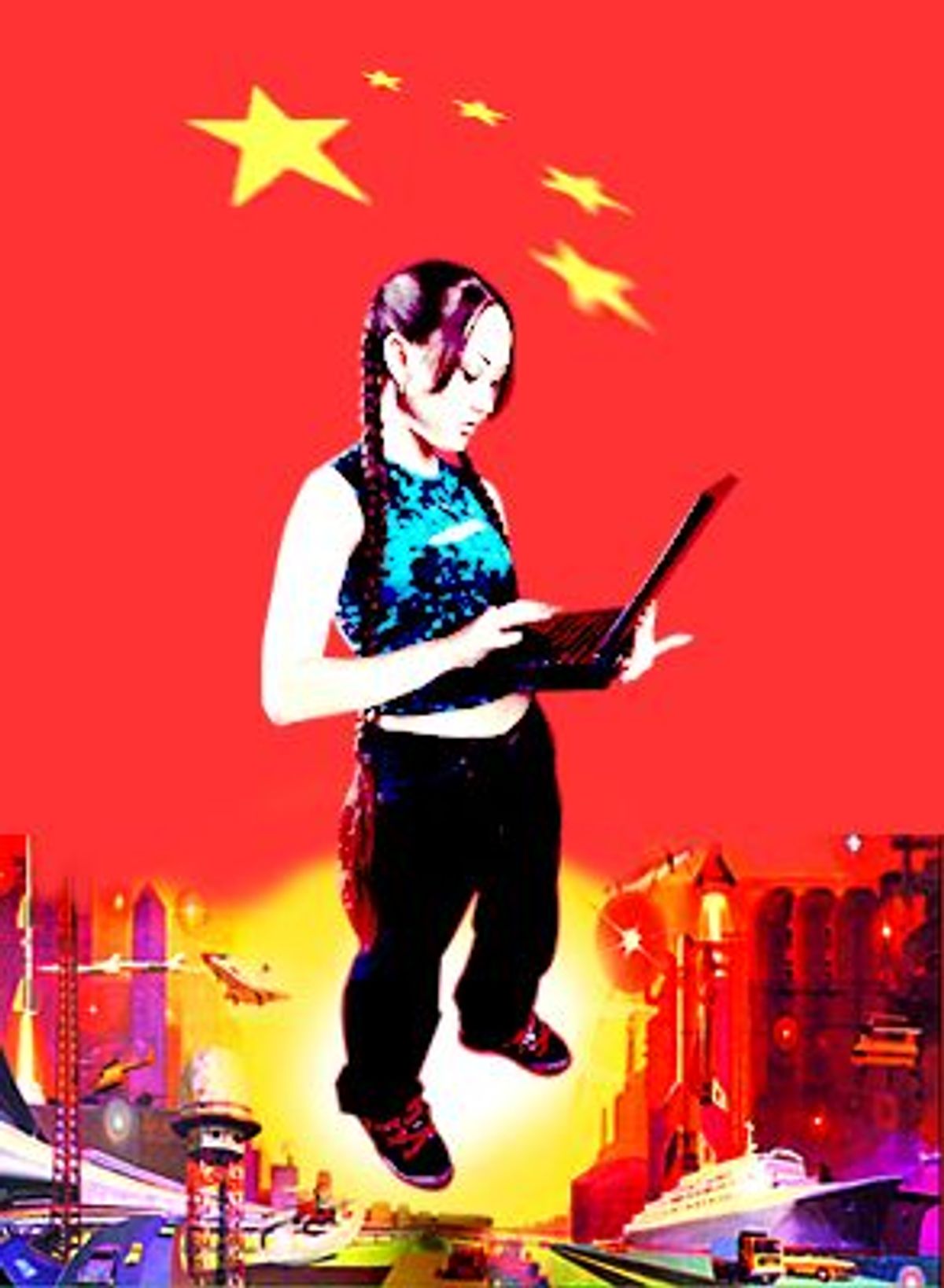

In Beijing, these tech-savvy young urbanites are known as the "Weiku generation." Weiku uses the Chinese characters for "great" and "extreme" to create a local version of the English slang phrase "way cool." It describes a generation of young, well-educated and relatively affluent Chinese hailing from broadly varied backgrounds. They have little self-concept of a shared identity, but are increasingly becoming a collective economic and social force to be reckoned with in China's cities. They also happen to represent the bulk of Chinese Internet users, and are uniting to co-opt the Web for their own purposes -- under the ruling Communist Party radar.

The members of the Weiku generation are a far cry from the 30-something entrepreneurs who officially represent the development of the Chinese Internet. A year ago, these dot-com hustlers were gods: During China's 1999-2000 Internet boom the bright-eyed founders of the country's earliest dot-com start-ups quickly became economic superstars. Lauded as the shining "Face of New China," these fast-rising aspiring moguls often shared one significant trait: a U.S. education. They brought back to their homeland an American entrepreneurial spirit, modern managerial techniques, billions in U.S. venture capital and a very American-like vision of the Internet's possibilities.

And like their American counterparts, these Internet carpetbaggers crashed and burned when bust followed boom. In a scenario all too familiar to Western eyes, they wasted hundreds of millions of dollars trying to be all things to all people, building elaborate portals that no one visited. These returning entrepreneurs had the money and the MBAs, but they didn't have the market knowledge -- the China they came back to was far different from the one they had left.

They may not have struck Internet gold, but they did achieve one notable success: They got the Weiku generation online. Motivated in part by the massive ad campaigns bankrolled by the start-ups, the Weiku generation started logging on and experiencing the Internet for the first time. And when they discovered that the portals weren't leading them to anywhere they wanted to go, they began to create their own destinations -- an organic, grass-roots Web of small niche sites, bulletin-board-centered communities and personal pages. In the shadow of billboards declaring "Subordinate yourself to the People and the People will take care of you," young Chinese Web users are now discovering and expressing their individual perspectives through the marketplace of ideas -- a place that can be found only online in closely controlled China.

Dissent in China is still a perilous activity, but in a country where formal organizations, even something as innocuous as a fan club for a pop star, are illegal unless created under government auspices, the Internet's capacity for bringing like-minded people together is both unparalleled and powerful. Topical Web postings have provided an underground network through which Weikus of similar interests from around the country can meet one another and organize everything from raves to rock concerts to art exhibits to avant-garde plays. The organic Internet being created by this generation may have only marginal financial prospects, but it promises a more important impact. For the first time in over 50 years, individuals in China are empowered by open, uncensored and unlimited access to information; are discovering their own voices in the forum the Internet provides; and are organizing themselves outside of the constrictive umbrellas of state, party, work unit and family. The Internet carpetbaggers had the money and the fancy degrees, but the Weiku generation is remaking China.

In 1994, the number of Internet users in China could be measured in the thousands. Today, according to NetValue China, 21 million Chinese are currently logging on. This represents merely 1.6 percent of the country's vast population, but it is expected to grow rapidly -- NetValue statistics indicate that 73.5 percent of China's Net users started going online only in the past two years.

Those two years, not coincidentally, saw the founding of a flurry of dot-coms bankrolled by Western investment and managed by well-educated Chinese who had observed the West's Internet boom from their classrooms at places like Harvard and Stanford. But by the time they were ready to jump into the Internet fray, the American market was saturated. So they packed up their diplomas and hurried back to the motherland they had left behind a decade earlier.

They were following in a long and honorable tradition as they came back to mold China in their own new-economy image. Returned students have played an important role in China throughout its modern history. Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek and influential writers such as Lu Xun studied in Japan in the first decade of the 20th century. Deng Xiaoping, Zhou Enlai and Ba Jin studied in France in the 1920s and '30s. The returnees now in their 30s were, in the 1980s, among the first group of students to go abroad since before 1949.

The returnees quickly established themselves in the emerging Chinese Internet market, with their access to American capital giving them an edge over potential local contributors. Their investment and business backgrounds helped them present their plans to potential investors, who in turn trusted the returnees' business savvy precisely because of their American education.

"Investors were comfortable with them; it was a matter of trust," explains Tony Zhang, a returnee who founded ChinaNow.com, a bilingual entertainment site. "Take [the lifestyle portal] E-Tang, for example: With six Harvard Business School grads, investors thought it was a sure bet, with a lot of money to be made." (Ironically, E-Tang's numerous Harvard pedigrees proved an impediment to its development; according to industry rumors, the company was riven by an ego-driven battle among its MBAs. Four of the original six have since left, and E-Tang refuses to comment.)

Money poured in. E-Tang brought in $48 million in investment, Sohu.com, China's Yahoo, $60 million; Sina.com, $68 million; and Netease, $70 million. The returnees became instant stars, and the foreign cash provided the Chinese economy with the infusion it needed to break out of its 1998 slump.

But almost as quickly as it started, it was over. Sohu.com, which listed on NASDAQ at a high of $13.125 on July 13, 2000, is now a penny stock battling to stay listed -- and Sohu is considered in good shape compared with many other sites. E-Tang and RenRen.com (a greeting card site) are scrambling for new business plans as their venture capital dries up. ChinaNow.com and ClearThinking.com, a business news site, are desperately combating rumors of their demise. Gaogenxie.com, a women's site founded by a fashion designer who left for the U.S. in 1983 with an American husband and returned only in 2000, is one of many to vanish from the Net altogether.

What went wrong? The same litany of mistakes that doomed Western start-ups can also be seen in China -- hubris, lack of revenue models, inexperience -- but the most obvious problem was the immediate inundation of the Chinese Web with portals. Everywhere you looked, there were ads for the new portal of the week, but very little Chinese-language material existed that could be searched for.

The portals tried to adapt quickly, setting up their own content sites, and foreign-funded general content sites also sprang up. But virtually all sites catered to a broad audience, attempting to offer a bit of everything for everyone; only a few latecomers sought to establish niches that would actually attract real people. According to Tony Zhang, "to do a niche Web site, you need to understand the niche. The founders don't, the investors don't, so they focused instead on the portals, expecting it to trickle down into the niche sites, but the economy collapsed before any trickling down could occur."

Ultimately, the chief legacy of the dot-com boom was the expansion of the Internet itself. Charles Zhang, an MIT Ph.D. who founded Sohu.com, says China's Internet growth would have started a good two years later if it hadn't been for the returnees and their American investment. Some analysts, though, believe this jump-start is precisely the reason that China's Internet boom imploded so rapidly: The market wasn't ready for it.

But neither were the returnees ready for the market. The generation that had spent a decade abroad did not understand what the generation that is flocking to the Net wanted. China is changing, fast, and the students who sought fortunes in the West have very little in common with the young generation that has surged to prominence in their wake.

The American-educated dot-com CEOs enjoy a few superficial similarities to the Weiku generation. Both represent the elite of their age group, both are more Westernized than other Chinese and both are full of bold plans for China's future and their own. But the similarities end there.

The returnees spent their childhoods in the chaos and terror of the Cultural Revolution. Most of their parents were intellectuals and academics, mainly in the fields of science and medicine. Seeing their parents purged, persecuted and "struggled against" as "rightist elements" and "poisonous weeds" was a formative experience for many, and probably influenced their later decision to leave China. Tony Zhang's parents, both doctors, were hounded because of their profession and their families' capitalist and nationalist backgrounds; he left for the U.S. in 1982, and his parents joined him three years later, not to return.

The Weikus, in contrast, represent a cusp generation, born toward the end of the Cultural Revolution. Their parents are mainly from ordinary backgrounds, and most had no chance for any education beyond middle school, as schools were shut down between 1966 and 1976. They were thus very focused on securing for their children the educational opportunities they lacked, and many Weikus are the first in their family to graduate from college.

Their memories are formed less by political chaos than by the economic deprivation of their childhood in the early 1980s, before Deng Xiaoping's economic reforms and opening to the outside world began to take effect. "Once a year, for Chinese New Year, our extended family would kill a chicken, and it was a big event. We had no candy then, so I would beg some sugar from my grandmother, mix it into a glass of water and drink it very slowly," reminisces a 26-year-old Shanghai musician. Most are only children, products of the one-child policy instituted in the mid-1970s, although the "little emperor syndrome" is reserved for somewhat younger only children who grew up in relative prosperity after China's economic reforms were already in full swing.

When the returnees came home, they found a China that had changed drastically from an impoverished planned economy to a bustling capitalist chaos. At the same time, so had they, and a gulf thus emerged between them and their friends and families.

Meanwhile, the Weikus had grown up and staked their claim to represent the future of China. Generally speaking, compared with the rest of the Chinese population, the Weikus are better educated, more culturally aware, more ambitious, more Western in tastes and sensibilities, more open to new ideas and -- influenced perhaps by post-Cultural Revolution cynicism -- resolutely indifferent to both authority and ideology. They may listen to the slushy Hong Kong and Taiwanese pop preferred by the masses with a certain guilty pleasure, but they vary their diet with both Western and Chinese rock.

Members of the Weiku generation dominate China's newly emerging avant-garde art and independent music scenes, and are also emerging as some of the newer stars in theater and film. A disproportionately large number of Weikus, after receiving visual arts degrees, went to work in advertising and design companies. Some of the more enterprising have launched their own companies, often in the areas of Web site and graphic design. They're willing to wear traditional business attire to work, but accessorize their clothes with a wry smile of practical irony. The officebound among them generally invest their surplus time and funds into riding the stock market and the latest fashion trends.

The larger Chinese society views the Weiku generation indulgently, as kids having their fun but who will snap out of it as they grow up. But it views returnees with considerably more ambivalence. Chinese popular culture is full of negative images of the returned foreign student as a character toadying to foreigners and authorities while condescending to Chinese who have not gone abroad. Pop rapper Zhang Zhenyu includes on his 2001 album a track about returnees titled "Bullshit." The song's narrative voice complains about a returnee in his office who flatters the boss while lecturing his fellow colleagues. "You say you've got an American degree, I say you're just farting!"

The returnees themselves, understandably, claim that there is little hostility toward them, mainly just envy of their superior opportunities and salaries. Tony Zhang says that in big cities, returnees are usually treated with respect. "Outside, though," he adds, "there's often a view that returnees have abandoned things Chinese, that they're a 'Western pig with a Chinese face.'" He concedes, however, that he doesn't "actually hang out with many returnees, as some of them have such superior attitudes toward the local Chinese."

Most of the Internet carpetbaggers failed to see the Weiku generation as ripe for exploitation. They targeted instead, for e-commerce reasons, an older and wealthier demographic group that is currently not online and evidences little interest in going there. That was one major mistake. But even the dot-coms that tried to go after a younger generation missed their mark. E-Tang defined a target group it called "Generation Yellow," as distinct from the "Generation Red" of the Cultural Revolution. E-Tang's press kit defines the group as "18-35 years old, educated, technology savvy and with a relatively high disposable income." The problem is that urbanites ages 18 to 35 encompass at least three distinct generations, with vastly different sensibilities and tastes: the 30-something Cultural Revolution babies, the 25- to 30-year-old reform-era generation and the under-25 post-reform group, those brassily demanding "little emperors."

"In China, things are changing so quickly, a new generation gap emerges every three to four years," according to Tony Zhang. "I think they [E-Tang] are very stupid. 'Generation Yellow' is the typical example of having been in the States too long."

"The portal landscape is over," declares Sohu.com's Charles Zhang. A look at where the action is appears to prove him right -- a fact that may have huge political implications.

Young Chinese Web surfers invariably report that they almost never visit the big sites, apart from Sina.com for news and sports scores, Netease for e-mail and Sohu.com for Web searches. Most of their time is spent on pages specific to their area of interest -- sometimes foreign sites made accessible with translation software but, increasingly, homegrown niche-oriented sites. Designers surf graphics sites, novelists visit literary sites, musicians frequent music pages and artists peruse online galleries. There is little brand loyalty toward the major portals, with interest reserved for small, specific sites founded by the users' peers or friends.

Niche sites generally are smaller and thriftier, and rely on word of mouth rather than glitzy ad campaigns to build their brand name. Their funds derive from activities that tie in with the site, rather than the traditional e-commerce and ad sales. A typical niche site is Shanghai's Menkou.com, which covers the club and music scenes and derives much of its income from event promotion. "Sites like this can't make much money," warns Murphy Wu, a Weiku hipster from Hangzhou and director of the Shanghai chapter of IandI Asia, "but with good customer service and a long-term vision, they can develop a loyal user base that will pay off in the long term."

One of Shanghai's most active Web personalities is a recent college graduate who is so subsumed by his online identity as "Bunnyman" that his friends rarely use his real name. A guitarist in an underground punk band, Bunnyman covers music for Menkou.com as a day job, but he also has his own music site, Rockself.com, and started and runs the Shanghai Rock BBS, a forum that is partly responsible for the phenomenal growth of the city's music scene over the past few years.

Other topical Web sites and chat rooms have similarly contributed to the emergence of virtual cultural communities. These sites provide a soapbox for individuals that China has never had before, even for those with volatile views. Dissidents with "dangerous" political ideas can host their messages on Web sites with foreign domain names, and less controversial material can be freely posted domestically.

The Chinese government views the growth of the Web in China with intense interest and glimmers of disconcertedness, recognizing its potential as a tool of both economic progress and political dissent. But so far, despite widely publicized (in the West) periodic crackdowns on dissident Chinese who use the Net, the government has actually taken a relatively positive approach, investing heavily in broadband infrastructure and research while encouraging state-owned enterprises and government bureaus to establish online operations. Apart from blocking foreign news sites like Reuters, the New York Times and anything concerning Falun Gong, the Communist crackdown on the Internet that everyone has been waiting for has yet to materialize, with regulations remaining overwhelmingly benevolent.

Which is not to say that people enjoy untrammeled freedom of speech on the Internet in China. Instead, most Chinese know what's acceptable and what isn't. Online chatters can get away with scathing criticisms of the government and the Communist Party, but most know better than to make actual statements of condemnation. For example, in a chat room or on a bulletin board, one can criticize an official, a policy or corruption, or can ask a question such as "Why is it so important to get Taiwan back?" But one can't come out and say "Taiwan should be free!" or "Down with the Communist Party!" There is free speech online up to a point, and that point is clearly delineated and widely known. The difference is that the boundaries of permissible speech on the Web are so much broader; what is the tightest of wiggle room in traditional Chinese media is a football stadium on the Internet. And right now, it is the Weiku generation that knows how to play ball.

The political passions of Chinese youth have long since been diluted by the market economy anyway, and while there is little fondness for the Communist Party, the Weikus see no point in replacing the bastards they know with the bastards they don't. What they consider more important is to push China's stagnant culture to start developing along with its economy, and to stimulate more critical thinking, now so lacking in cautious, conformist Chinese society.

But the proliferation of small niche sites is without question challenging to the party. Murphy Wu believes that while the government fears the Internet as a source of open information, the large sites are seen as safely self-censored. "The government is more afraid of these small, individual sites, which are hard to regulate and even harder to keep track of. They find these online communities particularly worrisome."

From a societal perspective the verdict on the Internet is still out. Activities like chatting and online dating are generally considered unhealthy, but even those have helped pry open a conservative society a little. Everyone I spoke with repeatedly stressed the new availability of information as the Web's most important contribution to China. The marketplace of ideas, kept closed throughout China's market reforms, has been forced open by the Internet. Books that are banned in China, such as those by Nobel laureate Gao Xingjian, can be read online, and manage to develop a strong following. People have access to real, undoctored, unbiased news. Niche sites, personal sites and online communities are thriving, and are likely to continue expanding along with the Internet's reach into the population.

Sohu.com's Charles Zhang sees an even larger impact. "For the consumer in China, the Internet is a vastly more important medium than it is in the U.S. There are few options here for real news, real information. Five years ago, nobody had a brain, but everyone has their own brain now. With more access to information, people are listening rather than just hearing, are thinking rather than blindly following directions. The Internet empowers the individual."

In a nation where individualism has been culturally taboo for several millenniums, where "the peg that stands out will be the first pounded down," the empowerment of the individual in the information revolution represents something more radical than Mao Tse-tung ever imagined. Its subtle subversions will be more momentous and long lasting, and perhaps more dangerous to the established order, than high-profile political movements like Tiananmen Square.

Shares