More than 80 million people in the United States and Latin America tuned in to "Betty La Fea," the telenovela in which an ugly woman navigates a world where beauty is generally all that matters.

High-profile Spanish-language columnists, politicians and pundits touted the show's feminist message, a rarity in the formulaic world of telenovelas. Respectable publications such as Colombia's leading daily, El Tiempo, dedicated entire columns to the soap's heroine, Betty, an unattractive but brilliant economist.

Betty message boards buzzed with e-mails from fans eager to discuss the previous night's episode. Even newspapers in the United States, which generally ignore Spanish-language television, reported on the "Betty" phenomenon as it captured record television ratings in the countries, including the U.S., where it had its finale in May.

Why, then, did this groundbreaking cultural event end with angry words from critics and widespread hostility from fans? Simple. It reverted to type and dashed the hopes of those who had watched it with a giddy sense of a revolution.

When Betty began airing last August on the Telemundo network, I tuned in wondering just how big a risk a telenovela would take. The soap was already generating buzz in Latin America, where critics were raving about the show's social message: Beauty is only skin-deep.

Like their English-language counterparts, Spanish-language filmmakers and advertisers had begun to learn that women are so eager to see realistic portrayals of themselves in the media that they are willing to throw their support behind any show that promises even the slightest hint of reality.

Telenovelas, however, have stubbornly maintained a traditional view of women's aspirations, one that equates female success with being beautiful and married. While there have been a few exceptions, most recently the Mexican telenovela "Mirada de Mujer," which told the story of a middle-aged woman who confronts life on her own after discovering her husband is having an affair, soaps have mostly remained faithful to a single plot involving a beautiful ingénue's search for love.

It was against this backdrop that Betty the Ugly One began.

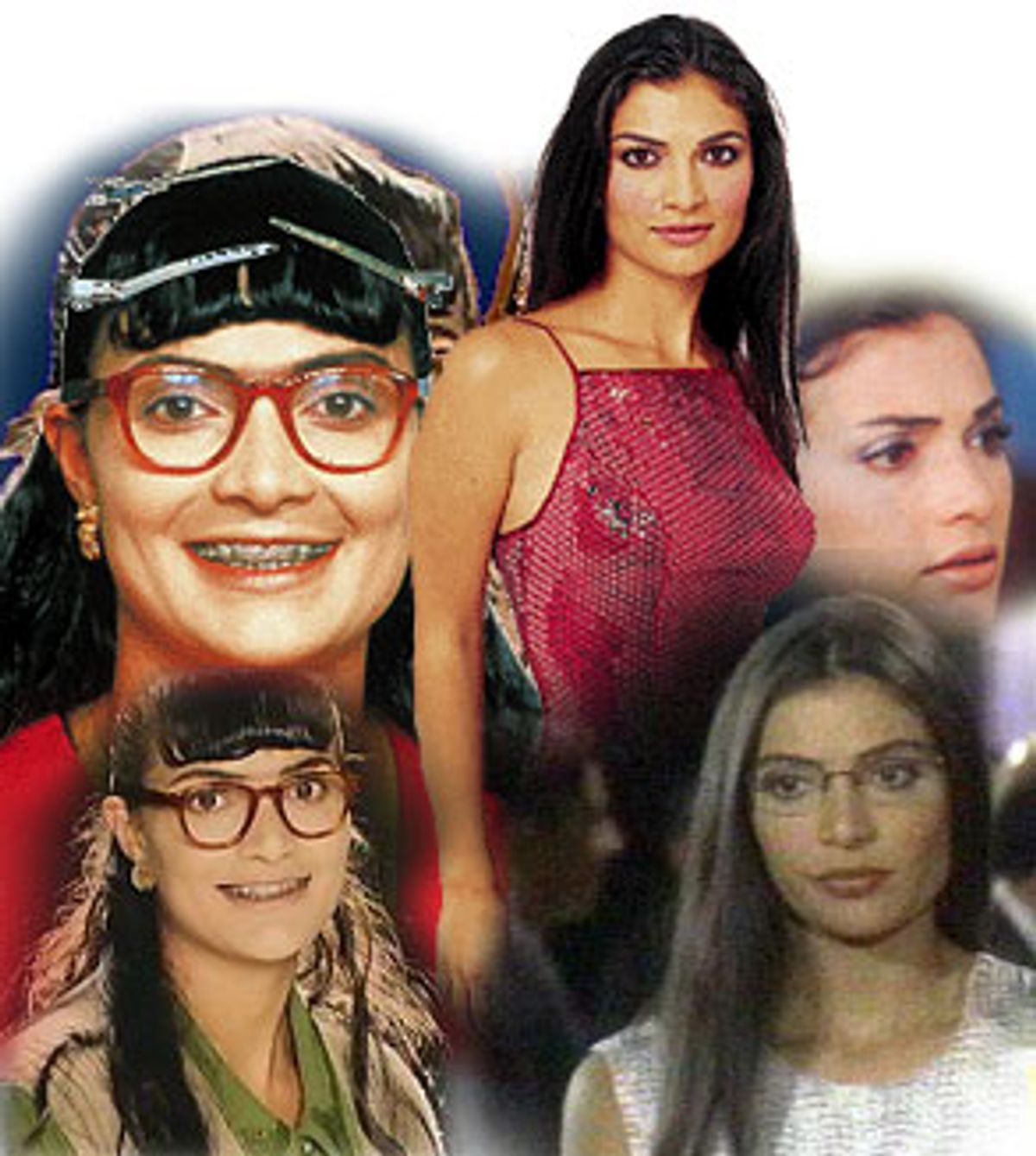

It was clear from the beginning that the show's creators understood how to get attention. In a world where heroines tend to look like Salma Hayek and Jennifer Lopez, they created an antiheroine who lacked the kind of stunning looks and physical attributes that cause men to propose marriage after just one meeting. With her thick glasses, braces and unibrow, Betty wasn't much to look at, by Latin standards. Her poor sense of style, squeaky voice and intelligence only made her plight that much more desperate.

And just in case viewers weren't convinced of the burden of her ugliness, the show's creators put Betty to work in a fashion designer's "house" and made her love interest a man who was breast-fed on beauty. Betty's Romeo was the owner's son -- a guy who had grown up thinking the average woman wore a size 2.

The premise was stunning: a woman whose appeal is her intelligence, humanity and humor struggles to be seen, heard and, ultimately, adored.

The show drew even hardened skeptics like me who believe telenovelas are made for housewives, retirees and recent immigrants whose language constraints force them to watch bad television.

I had watched a few soaps while growing up. My mother watched them religiously and through her viewing habits I came to know the formulaic plotline that usually involved a poor but beautiful girl falling for a rich guy whose family wasn't about to put up with their love affair. I came to regard telenovelas as the cinematic equivalent of Harlequin romances. They offered a kind of fuzzy, airbrushed image of love and life that lacked any realistic wrinkles or messy details.

"Betty," however, was unlike anything I had seen. I was hooked. I tuned in nightly. I watched as Betty was treated cruelly because she was ugly. The show's creators never spared her an insult or avoided a joke. Everything was fair game. The soap offered some of the most realistic portrayals of race and class in Latin America that I have seen on Spanish-language television, including a single mother struggling to eke out a living, a black secretary who insists her blind dates be informed of her race and a cast of wealthy personalities whose lack of empathy made them seem like Leona Helmsley clones.

The showed appeared to remain true to the philosophy of its creator, Fernando Gaitan, who was once quoted as saying that telenovelas are really about class struggle. For Gaitan, the telenovela was made for the poor, who live in a world where it is nearly impossible to get ahead. Other soaps were meant to offer an uplifting message in which downtrodden characters finally succeed, thanks to their love lives. Gaitan said his characters also succeeded, but instead thanks to their work.

Indeed, Betty climbed the corporate ladder, getting promoted from a lowly assistant to vice president of finance as a result of hard work. She never stopped trying and eventually captured the attention of her boss, a spoiled man who routinely yelled at secretaries, mismanaged the firm's assets and constantly cheated on his fiancée.

Slowly, Betty and her boss moved closer. He began to take notice of her as he struggled to keep the company afloat. She fell head over heels for a man who showed her some attention and kindness. Eventually the boss's interest in Betty moved from what she could do for his pocketbook to what she did for his heart.

And then, just in the nick of time, Betty sheds her ugly duckling image and transforms herself into a beautiful executive who struggles with the realization that her lover isn't a prince. In the end, Betty chooses to overlook his shortcomings and the two wed.

If Gaitan's message is that Betty moves ahead thanks to hard work and good old-fashioned smarts, the underlying text is very different. Apparently the antiheroine is intelligent enough to add the numbers but not smart enough to see her boss for the lying, cheating louse that he is. In the end, Gaitan gives us the same old message: Women can't find true happiness alone; they need a man to help them realize their dreams.

The message is so obvious -- and so reactionary -- that it has prompted angry opinion pieces accusing the show of being criminal for misleading the public. One Colombian writer mockingly said the country's attorney general could charge the show with a litany of crimes including fraud and abuse of the public trust. And in Costa Rica, where the show is still broadcast, legislators attempted to ban the soap midway through its run. (The soap is still being shown in several Latin American countries, including Argentina.)

Perhaps the biggest crime of Betty the Ugly One is that it missed the opportunity to bring one of the most popular Spanish-language television genres into the 21st century. Unlike the United States, where English-language films and television offer a broader range of female characters, Spanish-language viewers are confined to the small screen. Latin filmmakers struggle to put out a few movies, leaving viewers little choice other than what they get on the tube. So when viewers were promised a radical new character who broke stereotypes, millions of us tuned in.

What we got was the same old Cinderella story.

Shares