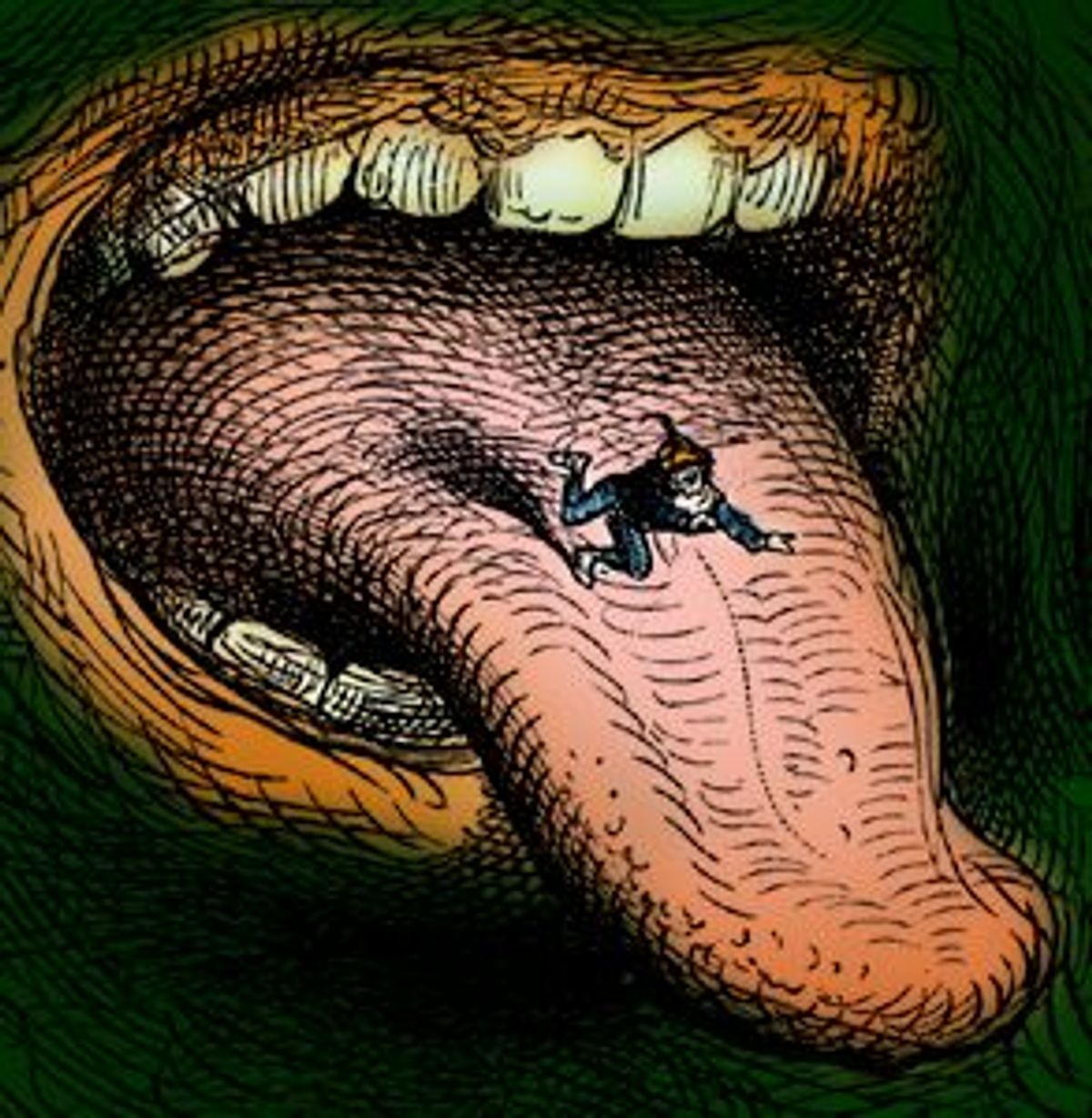

Once upon a time, a revolution brewed. Righteous artists, technologists and youthful entrepreneurs launched digital music start-ups, determined to take power away from the conglomerates that controlled the recording industry and deliver it into the hands of the little people. The dream was everywhere: Artists would use the Net to connect directly with fans and everyone would escape the tyranny of record labels and onerous contracts and overpriced CDs. Music would flow like water, and herringbone-suited executives in Hollywood offices would gnash their teeth as they finally received their comeuppance.

In those glory days, the Net gave birth to start-up after start-up dedicated to the proposition that online music had a brilliant future. Emusic.com, Napster, Nullsoft, MP3.com, SonicNet, Scour, IUMA, and dozens of other Web sites offered bold promises of how they would use the new medium to reboot the entire music industry. No doubt, much of the rhetoric was little more than marketing hype designed to give shaky start-ups a bit of power-to-the-people marketing cred, but for consumers weary of Top-40 radio and CD price-gouging, the vision was exhilarating.

Five years after it all started, the revolution is nowhere to be seen. The record labels, once railed against by those impertinent start-ups, now own their former enemies. Fiercely independent Internet companies have been picked off one by one by the same media conglomerates they once saw themselves as alternatives to. Through a brutal combination of business savvy, legal warfare and simple cartel power, the Big Five record labels have maneuvered the digital distribution industry into their control.

The process of consolidation and legal annihilation has been going for years, but the month of May witnessed an impressive flurry of activity. Vivendi Universal purchased MP3.com. Bertelsmann bought Myplay.com. Encouraged by its success at mortally wounding Napster, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) filed lawsuits against Aimster, a file-sharing utility that works with instant messaging software, and Launch, an Internet music site with impressive personalization capabilities. In the months previous, independent companies fell like dominoes: eMusic, Scour, IUMA, SonicNet, Musicbank, CDNow -- those that haven't been bought by their competitors have gone bankrupt or been forced to lay off virtually their entire staffs.

Selling out, it should be noted, isn't always a disaster. It's also a time-proven "exit strategy" and is often an explicit goal for software-related start-ups. It's also hard to know how many tears should be shed for companies like MP3.com and Napster; they were, from the beginning, just as greedy for profits as the record labels they lambasted. It's also difficult to argue with the reality that the studios do own the music so coveted by consumers and start-up entrepreneurs; it was always inevitable that they would fight to wrest back control of their content.

But what about all those consumers who bought into the revolutionary rhetoric and spent the last few years expectantly thrilled about the promise of digital technology: do-it-yourself radio, subscription services with all the world's music at your fingertips (the so-called celestial jukebox), personalized interactive streaming radio stations, and file-sharing services that introduced you to independent music you'd actually like? It's certainly not a victory for them that the big labels are taking control of online distribution. The recording industry's vision of the future is one in which we will all be paying $2.50 for every digital single we download or $.25 for every streaming song we hear -- and you'd better forget about ever swapping those MP3s with your friends or, God forbid, an All-Metallica-All-The-Time radio station accessible through your Web browser. Innovation is being sledge-hammered out of existence by legal threats and buyouts. It's all about control -- and right now, consumers are set to lose what little gains the Internet offered them.

The news isn't all bad for online music lovers. The indie spirit of the MP3 revolution is not entirely dead. Use of Gnutella, a distributed file-sharing program that isn't tied to a single commercial company, is skyrocketing in Napster's wake, and smaller music companies continue to burst forth with interesting ideas and amazing technologies. But the trend of events in the industry warrants caution. Gnutella's success will just make it a bigger target for an ever-more-confident recording industry, and any other company that raises its head high enough will also likely provoke a severe reaction. Meanwhile, the war is all but over for the original start-up guerrilla warriors -- those so bold to think they could cash in on a new medium without paying a price to the old regime.

Who would have imagined it? MP3.com CEO Michael Robertson, a roguish gadfly who was once happiest when delivering sermons against the evils of the recording industry, is now about to start working for his formerly avowed enemy.

"It is a little on the crazy side, and dripping with irony," says Robertson. "But I guess that's what makes the Internet so darn interesting."

When did everything start falling apart? Historians will no doubt pick over the remains of the early days of the Internet for decades to come, but it's probably fair to say that the success of Napster signaled the beginning of the end. Napster singlehandedly turned millions of consumers on to the world of MP3s. Before Napster, MP3 usage was steadily rising but still far from widespread, since mainstream music was hard to find. The advent of free, all-you-can-eat music changed that forever: with a few clicks, you could access the world's music, anywhere, anytime.

Napster got the recording industry's attention. Previously, the labels eyed the Net warily -- releasing the occasional downloadable digital single, chasing down the wayward MP3 pirate, lobbying Congress for strengthened copyright laws. But after an abortive start -- the RIAA's first online music-related lawsuit, aimed at stopping Diamond Multimedia's Rio MP3 player in 1998, failed -- the industry kicked into action. In Dec. 1999, the RIAA charged Napster with copyright infringement.

The courts, it would soon become clear, were the recording industry's preferred method for dealing with the upstart digital music industry. Mere weeks after Napster received its summons from the RIAA, a similar lawsuit was filed against MP3.com. The online MP3 search engine MP3Board.com came next, followed by Scour, a rival P2P service backed in part by ex über-agent Michael Ovitz.

In retrospect, the money spent by the RIAA and the recording labels appears well spent. Scour.com shut down its file-sharing service and sold the remains of its assets to a joystick company called CenterSpan (it has yet to relaunch). Napster sought cover by selling a controlling stake in itself to Bertelsmann -- usage of the service, according to the online entertainment news site Webnoize, has plummeted at least 25 percent.

MP3.com settled with the Big Five labels for an estimated $160 million. Post-lawsuit, MP3.com still had some cash in the bank, and saw profit potential in increased fees from its 150,000 artists (including the cost of on-demand CDs and a subscription fee for artists who wanted to participate in the Payback for Playback program), but the battered pioneer of the MP3 movement finally gave up on the idea of going it alone. On May 20, Michael Robertson sold the company to Universal, his former adversary, for $372 million.

The recording industry's approach to the digital music business appears to have been to wallop the competition with lawsuits until they gave up -- and then pick up the bruised remains to use to their own advantage. "The music industry looked at legal maneuvers as simply a business strategy," says Robertson. "And, quite frankly, years of lobbying have helped them construct a labyrinth of laws and rules and complexities and advantages. When you look across the digital music space, they've outmaneuvered Scour, Napster, MP3.com -- I don't think we're the only company that has suffered from being sensitive to legal maneuvers."

Even those start-ups that did manage to evade lawsuits haven't done well. Launching revolutions turns out not to be all that cheap. After the venture capital is gone and the stock price is under water, many impoverished music start-ups had to shut down or sell out. Emusic.com? Sold to Universal. Sonicnet? Bought by MTV, and subsequently dismantled by layoffs. IUMA? Bought by Emusic, and eventually shut down (although its remains are being revived by Vitaminic). Musicbank? Closed before it even opened. MyPlay.com? Purchased by Bertelsmann, where it joins CDNow and Napster. And those companies that can still boast of independence, such as ArtistDirect or Launch or Listen.com, are bleeding staffers and pinching pennies and on the verge of being delisted from NASDAQ.

What does it all mean? It'll cost you, big, to have a new idea in the entertainment distribution business.

"There is right now a climate of oppression among inventors, who are unable to market, fund or even freely distribute their work," complains Johnny Deep, the founder of Aimster. "As [RIAA head] Hilary Rosen has said, quoted by Larry Lessig, 'unless we approve, your idea will not be permitted. It will not be allowed.'"

Without recording industry support and music licenses, distribution platforms like MyMP3.com or Napster or Launch have no major artists to (legally) distribute and therefore, no mainstream customers. The record labels have been notoriously stingy with those licenses; and even when they do grant the rights to their music -- for example, in the case of the LaunchCast radio station -- the labels are quick to employ the industry-friendly Digital Millennium Copyright Act to micromanage exactly how the music is listened to.

"There is no place for a small company to pull off a monster vision in digital music," says Robertson. "If you're making a tiny widget that's a bolt-on feature for listening to music, fine -- that can be a small company. But if you want to be the grand vision, the place where everyone stores their music and listens to it wherever they go, that's a very big undertaking and a small company simply cannot do that. What you're witnessing on the digital music front is that all the small to medium companies are going away. The window of opportunity is over."

With the promising early dot-com music companies falling by the wayside, who is stepping into the void? Naturally, the record labels, now setting themselves up as online distributors. Not only are individual record labels like AOL Time Warner, Bertelsmann and Universal scrambling to set up their own Napster-like services, distributing their own music on P2P platforms, but the entire recording industry is now dividing into two larger camps for distributing music licenses. The upcoming MusicNet and Duet platforms are supposed to step in where MP3.com and Napster are being forced to step aside. MusicNet (a partnership of AOL Time Warner, EMI, Bertelsmann and Real) and Duet (Universal, Sony and Yahoo) are both setting themselves up as music-licensing platforms that will sell the labels' catalogs for subscription services -- of course, available only in their chosen music formats, and only to carefully approved music services, and only in low-quality streams.

"If you are a small player, you're kind of locked out of the game now," Robertson says, explaining his decision to sell to Universal: "It's shaping up to be a two-horse race: MusicNet and Duet, with Duet powered by MP3.com."

The power, then, is consolidated squarely back in the hands of the same record industry executives that held the reins before. Everyone with a good idea that doesn't fit into what the music moguls have already deemed appropriate is out of luck. That personalized radio station will be shut down, that peer-to-peer network will be decimated before it even has a chance to offer a subscription plan, prices for music downloads will be set sky-high, and new music-exchange services will contain only limited catalogs.

The loser in this equation is, of course, the customer, as the pre-Internet status quo of high-priced CDs and generic radio playlists is simply replicated for the digital age.

The digital music start-ups were hardly saints or true freedom fighters by any measure -- many were plagued by greed and blithe disregard for the rights of artists. But they were all focused almost entirely on customer-friendly innovation -- personalization, portability, interactivity, access to hard-to-find tracks, exposure to new music. Wooing customers was a requirement for the start-ups.

It might be possible that in the long run the recording industry will pull through for customers -- that one or all of these upcoming, label-endorsed competing music distribution services will offer significant catalogs of music at reasonable prices, that unique online radio stations will blossom once licensing issues are ironed out. It's also possible that Congress, which is currently reviewing the activities of the record companies and debating the merits of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, will step in on the behalf of the start-ups.

Digital music is not dead. There are hundreds of companies that are still innovating or offering new ways to listen to music -- whether online radio stations like those at Live365.com, or small independent MP3 download sites like Epitonic, or groovy technologies and add-on applications like Kick.com. And statistics for Gnutella are through the roof -- according to Clip2, which monitors the P2P service, Gnutella use grew 4 percent in the last week of May alone. Since March 4, Gnutella traffic has risen 400 percent, thanks in part to user-friendly applications like BearShare and the frantic work of programmers who have shored up the technology's weakest links. For every Britney Spears song you can no longer find on Napster, you can find 10 copies on Gnutella.

The prospect of anyone making money off of digital music other than the recording industry that is so successfully defeating the online rebels is a different story. There is no middle ground. The demise of digital music dot-coms points to a future in which the music industry is utterly split between for-profit, label-controlled services, and decentralized distribution technologies designed to evade and circumvent the authorities. How that story will play out is impossible to say yet. Gnutella may eventually succumb to the might of the RIAA, which is already making noises about targeting software developers, ISPs and individual users of the network with lawsuits.

But the Internet itself is fundamentally about making distribution of content easier. If Gnutella falls, another Gnutella-like structure will rise. So far, hackers have always found another workaround. There will always be music-loving programmers who want to continue to innovate on consumers' behalf, with or without the approval of the RIAA; and as long as the record industry continues to exploit consumers and artists, that's exactly what those programmers will do.

The collapse of the independent digital music industry brings us back to the beginning, back to the truly do-it-yourself indie roots of the Net's earliest days. Collective projects that are free from any corporate ties are still flourishing, and small companies with nifty ideas lurk on the fringes. The major record labels, in turn, will do what they've always done: They'll take advantage of their newly acquired Internet start-ups to develop music services designed to reap an already profitable industry even greater profits.

Could it ever really have been any different?

Shares