Those who believe, as most sensible people do, that the current war on drugs is a boondoggle and a disaster also usually say that we ought to be spending our dollars on treatment, not law enforcement, if we want to diminish the trade in illegal drugs. As long as rampant demand -- in the form of a buzz-hungry populace with fistfuls of ready cash -- waits inside our borders, enterprising individuals and organizations in other countries will find a way to supply it, no matter how many helicopters we send to Colombia or smugglers' boats we seize off the coast of Florida. Menacing teenagers will shoot each other on street corners and grizzled bikers will cook up methamphetamine in backwoods sheds provided there are enough people, in the end, willing to pay enough money for those little packets of white powder. (Or at least as long as selling that white powder remains against the law, but let's stay in the realm of political possibility.)

But if "treatment" has become a buzzword for citizens tired of seeing billions of their tax dollars wasted on hunting down South American drug lords and warehousing nonviolent offenders in prisons, Lonny Shavelson, a physician and journalist, argues that it's often not a whole lot more than that. In his new book, "Hooked," which follows five addicts through the torturous process of getting help for their substance abuse problems in San Francisco in the late 1990s, he makes a powerful case that America's drug treatment program is hopelessly flawed. Despite "a burgeoning movement in states across our nation to shuffle drug offenders from prison to treatment," he writes, "before we shift hundreds of thousands of addicts into rehab, we must first treat the treatment system."

As these five stories unfold -- at times "unravel" seems the better word for what happens -- the truth behind Shavelson's prosaic play on words becomes agonizingly clear. Lives are ruined and lost, hearts shattered, precious second and third chances squandered, trusts betrayed, hopes stubbed out. And, in a few rare cases, people do manage to miraculously pull themselves out of the pit. Shavelson wants to see those exceptions become the rule, and in figuring out how we can make that happen, he overturns a few of our most cherished notions about addiction and recovery.

The five people he writes about in "Hooked" are part of the kernel of hardcore substance abusers whose lives, according to Shavelson, constitute the front line of the drug war: "the most resistant, demanding, often unlikable, and arguably the least deserving of treatment service ... precisely the type of difficult junkie that rehab programs must succeed with if they are to make a dent in the crime, violence, and craziness that comprise the drug problem." Although the number of illegal-drug users in the U.S. declined from 1979 to 1998, the number of drug-related hospital visits and deaths went up, and most people picked up by the police for criminal offenses test positive for drugs. The Justice Department says drug users account for "an extraordinary proportion of crime."

Shavelson documents their blasted lives: Darrell is a lonely, homeless alcoholic and crackhead who has flunked out of several rehab programs, attended thousands of Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and been hospitalized for countless injuries, including falling out a window, while wasted. Mike is a skilled plumber whose unendurable memories of being molested as a child send him back to heroin again and again despite his heartbreakingly fervent desire to redeem himself in the eyes of his kids and girlfriend. (In the book's opening pages, Mike is described as shooting up while driving a truck down California's Highway 101 -- steering with his knees -- getting in a wreck and then, once ascertaining that he's uninjured, continuing to shoot up in a ditch beside his totaled pickup.) Glenda is a tiny, sweet-natured Native American who has been drunk and homeless since age 16 and looks 60 instead of 37, her actual age. Crystal is a cocky crackhead who boasts of her fearsome street reputation until she trusts Shavelson enough to confess that she was a streetwalker and a "victim." Most daunting of all is Darlene, whose auditory hallucinations ("noises," she calls them) could be caused by psychosis, or by the speed she injects as often as twice a day, or by the brutal conditions of her life in various homeless encampments, each makeshift shelter eventually bulldozed by the authorities without warning.

However desperate their situations, these five people entered treatment at an opportune moment. In 1996, the new U.S. drug czar, Gen. Barry McCaffrey, shifted a bit of the nation's drug policy focus from law enforcement to rehab, declaring that "effective treatment can end addiction" and that drug policy goals "can only be accomplished with a significant expansion of capacity to treat the nation's drug users." (Most of the money, however, still goes to enforcement.) And San Francisco had launched a much-ballyhooed "treatment on demand" policy that promised to get all addicts seeking help into a treatment program within 48 hours. You'd think that seeking rehab just at the time when officials had recognized the importance of treatment would give these addicts a boost -- but you'd be wrong.

According to Shavelson, the main factor causing people to abandon their search for rehab is basic bureaucratic disorganization on the part of treatment providers. That's not the kind of ideological beef that makes for chest-thumping Op-Ed columns, but it's the kind of problem that causes vast sums of money to be sucked up into a system that offers scarce positive results. Addicts have to make their way through a chaotic patchwork of services and programs, each covering a small, specific need and each looking for a reason to refer difficult clients elsewhere. Negotiating this thicket of paperwork and conflicting agendas makes dealing with the average HMO seem like a snap and -- guess what? -- organization and persistence are not common traits in drug addicts.

For example, the question of whether Darlene's aggressive, incoherent behavior results from mental illness or substance abuse (speed can induce psychotic symptoms) -- a question that, as Shavelson points out, isn't particularly relevant to helping her -- stymies her progress through the system. He describes her experience as "a cyclonic quest for rehab: referred to and then immediately kicked out of three drug treatment programs ... referred by the city's mental health counselors to the substance abuse counselors; referred back to mental health again in circles that have spun me dizzy just watching."

For another example, Glenda, joyfully sober for the first time in decades after three months in a terrific Native American-run inpatient program, steps out of it and into a treatment vacuum. The room found for her is in a "clean and sober" Salvation Army housing facility, but it's three blocks from the place where she used to hang out all day drinking with her street pals, and no one supervises her recovery beyond the Salvation Army's weekly drug tests. Two days later, she's drunk again and kicked out of her room and onto the street. A year and a half after that, she's dead.

Shavelson convincingly argues that all the money spent on treatment programs will go to waste unless each addict is assigned a case manager, someone who can guide him or her through detox (which "provides medical social services during those days it takes to get sober and withdraw"), then rehab (a program that seeks to resocialize the addict in a clean and sober environment) and finally getting the housing and employment he or she needs to become a functional member of society. Instead, he observes irately, "the seeming lack of any management that could impose order on the myriad substance abuse programs and services that have proliferated since the mantra of rehab took hold across the country" means that people get briefly cleaned up and then dumped back into the nightmare from whence they came, without anyone accounting for their need, as Mike puts it, "to learn how to live all over. Like from the beginning."

Mike, though, ran up against more than just bureaucratic hassles and inadequacies. After weeks of waiting to get in (during which time he almost died of an overdose), he became a model member of the famous San Francisco "therapeutic community" Walden House, but then relapsed shortly after moving on to transitional housing. Afraid of going back to Walden to plead for readmittance, he went on a heroin binge, then tried, without much success, to stay clean on his own. Shavelson sees this, too, as an avoidable calamity. Walden adheres to a common rehab philosophy that Shavelson calls "abstentionist." It imposes a long list of regulations on house residents, and punishes even the slightest infraction with long periods of "reflection" time on a bench in the communal hallway. A major violation like Mike's relapse means automatic ejection from the program -- unless the prodigal submits to a grueling group meeting in which he must sit in a chair in the middle of the room while the entire community pelts him with accusations and abuse.

This militaristic, "tough love" approach has disreputable roots in the scary Synanon movement that started in the late '50s and flourished in the '70s. Synanon, which practiced a form of "attack therapy" called "The Game," eventually was discredited when its cultlike antics expanded to include stockpiling weapons and placing a live rattlesnake in the mailbox of a lawyer who'd sued the group. Nevertheless, with some significant toning down of its more extreme aspects, the Marines-like, zero-tolerance model persists in therapeutic communities like Walden, which claim that the addict is like an irresponsible child whose personality must be broken down and rebuilt from the ground up in a highly structured, rigorously sober environment.

While it no doubt works for some people, Walden's strategy spectacularly failed Mike. Shavelson considers it abusive and self-defeating and points out that Mike's underlying psychological problems (particularly intrusive, recurring memories of being raped as a child) never got treated at Walden. The constant demands of the community's daily routine kept Mike distracted from his demons much as heroin once did, and the harsh, humilation-based methods used to reinforce the house's regimented lifestyle discouraged him from opening up about a past he remembered with tremendous shame. Worst of all, when he relapsed -- which most recovering addicts do -- the emotional ordeal that is the price of returning to Walden was more than he could face.

Not surprisingly, a new treatment philosophy has emerged in recent years, called "harm reduction." One advocate tells Shavelson that harm reduction defines what it wants from addicts as "any positive change." Its first commandment is "Meet the clients where they're at." Instead of jettisoning addicts from the program if they don't stay clean, harm reduction offers them different kinds of services, congratulates them for using fewer drugs and does whatever it can to help them "have less violent lives, steal from fewer people, become somewhat less crazy, and even, possibly, a bit happier." The zero-tolerance side considers harm reduction to be an unconscionable betrayal of the addict, who is engaged in a life-or-death struggle in which halfway measures don't work. (One of the drug users Shavelson interviewed, Darrell, agrees.) McCaffrey condemned harm reduction as a plot devised by drug legalization advocates.

Whichever approach works best, the existence of these competing approaches has resulted in a "drug treatment world ... divided into two armed, deeply entrenched encampments that to this day continue to fire bullets of contempt at each other's rehab philosophies." Shavelson clearly favors harm reduction, particularly in the case of someone like Darlene. Remarkably eloquent despite the utter confusion of her life, at one point she drags Shavelson into a store and shows him the cover of a comic book:

It's a busy, medieval scene. Dark, ominous castles are surrounded by wooden carts filled with dozens of blood-soaked, nearly naked women's bodies. Men in armor, holding swords, gawk at their exposed, bloodied flesh. I look at Darlene, puzzled. "Shrinks always want to know about the noises in my head," she says ... "That's a picture of my noises. It's the place I don't want to go no more."

She later explains that she's afraid to stop shooting speed because the "noises" might not go away and she'd be proven to be crazy. Darlene may indeed need structure in her life, but first she needs intensive professional psychotherapy.

Yet Darlene does, eventually, make it to Walden (albeit in a special program -- one that wisely combines full psychiatric care with drug rehab). So does Crystal, a rehab candidate who, while free of psychosis, is almost as unpromising as Darlene because she enters the system without the slightest desire to get off drugs. Shavelson, ever the pragmatist, doesn't think much of the bullying ways of attack therapy, which addicts voluntarily endure. But he finds himself, to his astonishment, endorsing a practice that superficially seems even more disrespectful: coerced treatment. The reason is simple: He has seen it work. Glenda, the most "pitiful, disheveled, near-death, long-term street alcoholic" he had ever known, was kidnapped and forced into rehab by concerned homeless service workers and came out "three months later -- cleaned up, sober, and healthy."

The system ultimately failed Glenda, but it succeeded with Crystal, who was charged with selling crack and sent to San Francisco's drug court instead of criminal court. Drug courts, originally established in Florida while Janet Reno was the state's prosecuting attorney, supervise an addict's recovery in much the same way that Shavelson envisions case managers doing it, from detox to rehab and on through getting a GED, getting out of debt and finding employment. The addict is required to take regular drug tests and report to the court every two weeks. If the addict doesn't comply, he or she is sent back to criminal court to face jail time. There's ample evidence that drug courts have the highest success rate -- that is, the lowest dropout rate and recidivism -- of any method of dealing with addicts, therapeutic or criminal. And this despite the fact that they fly in the face of one of the recovery movement's core truisms: that a substance abuser has to be truly ready and willing to quit in order to get sober.

Boasting from the start that "I can fake my way through any program. I'll take 'em for what they got," Crystal graduates two years later a changed woman. Shavelson attributes this success to the fact that despite her relapses and occasional truancies, the drug court judge and rehab team "simply [stuck] to her like glue." More an exquisite piece of theater than it is anything else, a drug court walks its charges through a predictable series of rebellions and transgressions, intensifying treatment when they start using again instead of kicking them out, manipulating them into the kind of program they need. The threat of being sent back to criminal court is the drug court's stick, and lavish praise for those who clean up their acts is its carrot. Crystal's stint in Walden is predictably "stormy" and she shrewdly observes that "when things get deeper at Walden than 'Don't do dope,' they don't know how to deal with it. But I talked to the judge and my Drug Court case manager and they're insisting I have a therapist at Walden 'cause I need some real help with this depression or I'll be back on the crack pipe."

The great irony of drug courts, though, is that you have to be a criminal to end up in them. Darlene, who supported herself with petty thefts but never got caught, managed to get the care she needed only because Shavelson went to bat for her, getting her a meeting with a gifted psychiatrist and pleading her case when his clinic tried to have her kicked out for threatening a worker. Mike does eventually wind up in jail for burglarizing his sister-in-law's house for drug money, but stands little chance of getting into drug court because the break-in was residential, not commercial, and prosecutors don't want to seem to be coddling offenders who have been "terrorizing the community." Not only that, but because he has been convicted of a couple of other minor, nonviolent felonies in the past, he faces a three-strikes penalty of 25 years to life -- a grotesque travesty of justice, given how badly he wants to be a responsible husband and father and how well he might do with the right kind of help.

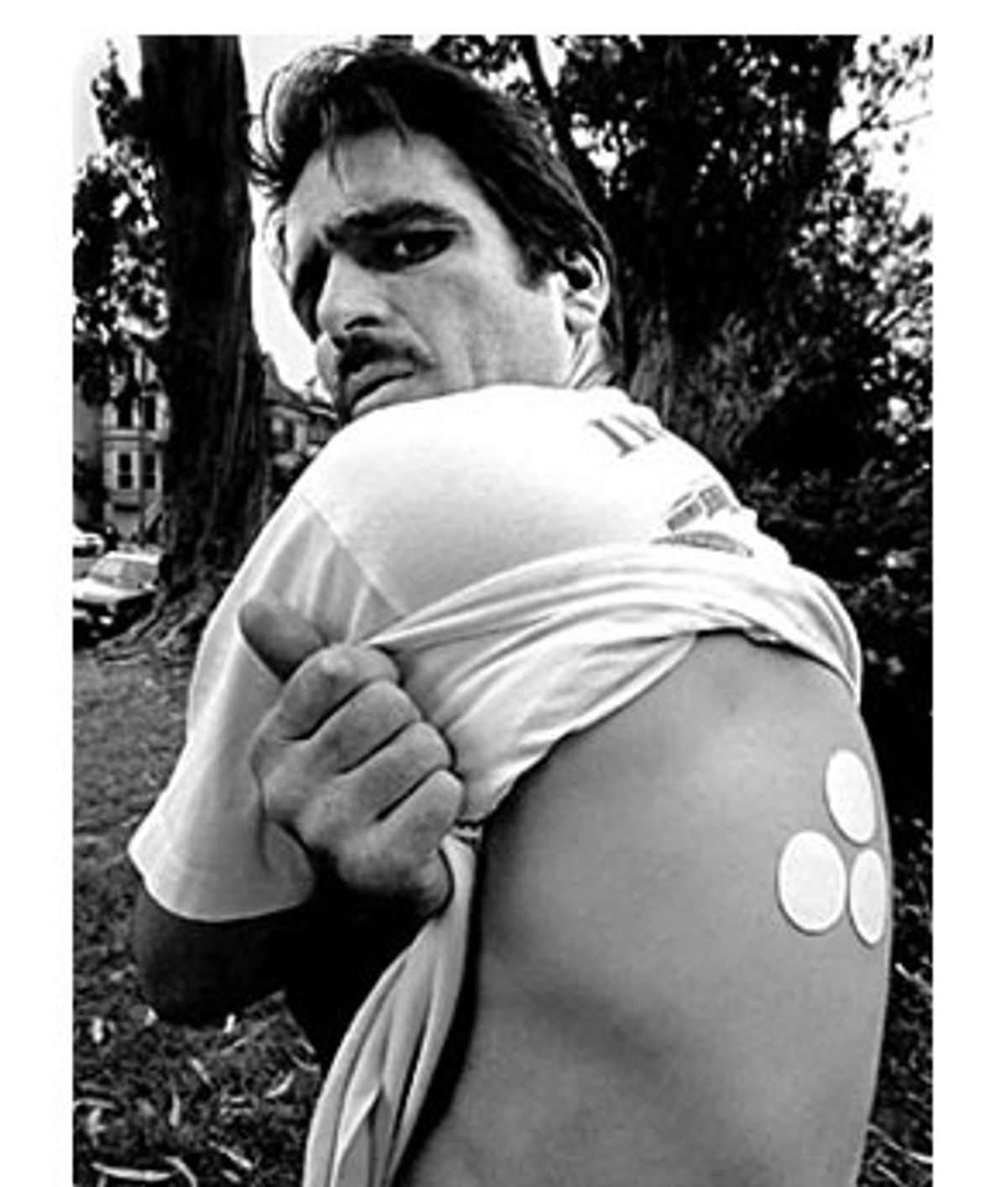

"Hooked," with its tales of lives horribly mangled by everything from childhood abuse to mental illness to bad luck and, of course, addiction, gives the lie to the boot camp mentality that prevails in our public conversation about drug abuse. You need only look at the "before" and then the radiant "after" photos of Darlene and Crystal (beaming as she graduates from drug court) to see the kind of results that playing drill sergeant will never get us. Drug courts -- derided by some as "hug courts" -- don't coddle addicts, but they don't abuse or abandon them either. Shavelson has good things to say about a recent judicial mandate in New York that would send nearly all nonviolent drug-addicted offenders into rehab, but cautions that California's recently passed Proposition 36 doesn't insist on the kind of coordinated monitoring needed to make its similar directive pay off.

If you believe, as I do, that the war on drugs is really just a job creation program for people who'd otherwise be out of work now that the Cold War is over (the spooks and soldiers go to Colombia and the weapons-plant workers go to the prison-industrial complex), then, alas, it's hard to see the kind of revelations found in "Hooked" having much effect on public policy. Despite McCaffrey's own endorsement of the drug court model, you just have to do the math to see that things haven't changed that much. As McCaffrey left the Office of National Drug Control Policy at the end of 2000, the 2001 budget allocated $50 million to drug courts, $420 million to new prisons and $1.3 billion to fight the drug war in Colombia.

Shares