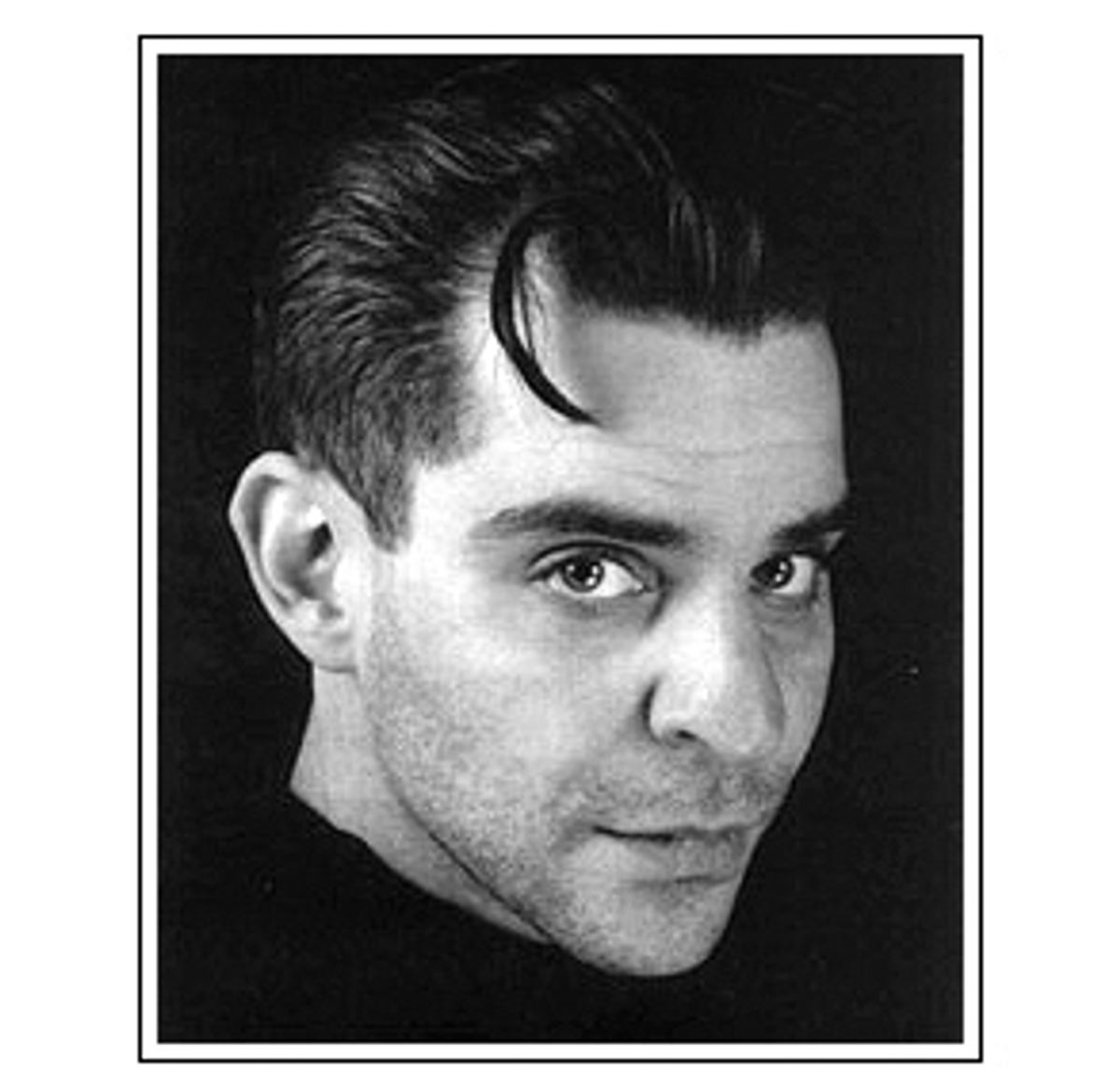

When I met David Rakoff, whose new collection of essays, "Fraud," was published last month, I expected to encounter a chain-smoking, hard-drinking, acid-tongued terror who would quickly put me in my place with a few well-chosen words. I expected the bastard son of Addison DeWitt and Fran Lebowitz.

Instead, he was a gracious, generous and gentle soul. No vitriol, directed at me or elsewhere, was in evidence. I was both relieved and disappointed, like the gullible Weather Channel viewer who girds himself for the Storm of the Century by stocking up on salt, bottled water and other supplies, only to wake up to a mere dusting of snow.

Rakoff warns us in the very title of his book that he is something of a fraud, a cowardly lion whose tough talk hides his fears and insecurities. But then we are all frauds in Rakoff's world, all deserving of both flagellation and forgiveness.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

How has your association with "This American Life" impacted your career?

It didn't just impact my career -- it made my career. It's like being awarded a driver's license without having to learn how to do left turns or parallel parking, just because they want you on the road. That doesn't happen. So I'm incredibly lucky in that way.

You've also dipped your toe in the acting waters from time to time over the years, most recently off-Broadway in David and Amy Sedaris' play "The Book of Liz." How do the two disciplines differ?

They're different sets of muscles. I was going to say that writing is about disclosure and acting is about obfuscation, but that's such a little lie. Both of them are about obfuscation and masking oneself.

Is the act of writing about masking oneself, or about revealing oneself in the light you prefer?

That's the thing: It's about revealing oneself on one's own terms and about bullying people. [Laughs] It's interesting -- what's nice about acting is that it's work that involves other people daily. As you know, writing is not. So it's been nice to do this play, which has taken up the last quarter of the year -- we were up for three months. It's great to be with people.

Does reading your work in public satisfy that same performing jones?

Yes, it does, definitely. It might even be a little more substantive because the words are your own.

Nearly every piece in "Fraud" finds you in one way or another an outsider. Do you seek out such situations?

Oh, sure. But I think pretty much everybody feels like an outsider most of the time.

You've a number of traits that might lead some to consider you an outsider: You're gay, you're Jewish and you're an expatriate Canadian. Have you ever felt pressure from any of those communities to be more of an activist, to more avidly embrace your sexuality, your ancestry or your nationality in your work?

Within the world that I run in, which is a very privileged, insular, small New York world, they're so normative, and I'm so much a type, that it's not really an issue. But, simply put, I think it's far more politically significant that Outside magazine allowed me to, unself-consciously and completely without comment, be visibly, notably gay in a feature article I wrote for it ["Back to the Garden," a revised version of which appears in "Fraud"]. It didn't have a problem with that at all, and I don't think anybody noticed. But that seemed significant to me.

It's an interesting piece. While reading it, I felt a certain interventionist concern for you. You are such an urban being. I became worried that you seemed to be buying into the whole back-to-nature/survivalist training you were undergoing.

The thing that really appealed to me was the stuff you got to make and do. It's like arts and crafts, but the stakes are life and death. I enjoyed making the things in the wilderness. I found that kind of mastery, that sort of dexterity, is something that really appeals to me; I like to make stuff. I'm handy that way.

There's a certain challenge such groups like to present, along the lines of "If left on your own out in the wilderness, would you survive?" My answer is no, I wouldn't, and I couldn't care less. If society suddenly breaks down, and it's survival of the fittest, I'm prepared to throw in the towel.

That's the thing. There are so many other things that would lead up to such a societal breakdown -- the looting, the pillaging, whatever. You'd be dead anyway. It's very rare to be suddenly and hermetically placed in a full survival situation. It's pure child's play, a boy's fantasy.

You grew up in Toronto, a cosmopolitan, cultured city in its own right. So what is it that brought you to New York? And what keeps you here?

There's no underestimating the history, the sheer historical power, of this city. It's manifest throughout music, movies, literature, whatever. But what keeps me here is that I've been here for 18 years. It's where I became a grown-up; it's where most of my formative experiences happened. I groove on -- groove on? -- that certain direct quality, the emotional immediacy. While Toronto is certainly polite and apparently kind -- and it is kind -- there's a social infrastructure that there just isn't here; there's a kind of chilly reserve that I no longer enjoy.

I enjoy the fact that, here, everyone in the bank has an opinion about what I'm doing.

Are you living the life you imagined as a youth?

I'm the luckiest person I know. I'm just waiting for the other shoe to drop, checking for lumps. I'm incredibly fortunate right now. The life I lead is different from the one I imagined when I was younger, but equally wonderful. Because it's real, so it's very different. You know, all things that are real are different from the febrile fantasy version of them. So it's more difficult, but it's richer. It's more nuanced and ... sadder.

But no one's fantasies ever encompass sadness -- even my own. Which is weird, because sadness is a part of everything I think, say, sleep, eat or do. But I'm unbelievably fortunate right now -- so much so that it freaks me out a little bit to talk about it. You know what I mean?

I absolutely do. You're where I was a year ago, when my book had first come out, and I simply couldn't believe my good fortune. I felt that I was somehow mistakenly living someone else's life. I used to half-joke that I was on the lookout for runaway buses.

It's funny you say that. The last time my life was going so well was when I was 22 and living in Tokyo, and then I was briefly felled by that little illness [Hodgkin's disease]. That seemed to be the equation of my life.

May 15 was the book's pub date, and though I should probably be embarrassed to admit it, I was definitely, on some level, convinced that I wouldn't actually live to see May 15. I had to fly back from Canada on May 15, and I thought, Well, this is it. Then I realized that, of course, that wasn't the case, because God's not as big a drama queen as I am!

What impact did that bout with cancer have on your life? Having survived a serious illness, do you now live life with more gusto?

No, I don't live with any more gusto; I am still as tremulous and trepidatious as ever. But you must also understand that I felt somewhat dilettantish compared to the other people at the cancer hospital. And that was followed by my moving back to New York at the height of the [AIDS] pandemic. But it had a huge impact on me. It taught me things that are both very ethereal and very direct and pragmatic. Altruism is innate, but it's not instinctual. Everybody's wired for it, but a switch has to be flipped. I don't think that people are naturally sympathetic to other people in that way. So I think having been on the other side of that membrane gave me an appreciation for frailty that I might not have had otherwise.

If you were to be diagnosed again with something, do you think your reaction would be, "Oh no, this time it's got me," or something more like, "Well, I beat it once, I'll beat it again."

It's sad to say, but I would probably shut down emotionally in precisely the way I did last time and become just as adamantine and impenetrable. But at the same time, there would also be a sense of "Well ... finally! What have you been waiting for?"

If you could swap careers with anyone, who would it be?

Without his politics? Jerome Robbins. I'd be a dancer. Or Gene Kelly.

Are you able to read other writers ...

Without feeling bad about myself?

Exactly!

No. [Laughs]

Do you ever say to yourself, "Gosh, I wish I'd written that"?

Sure. Well, more like "Who the hell do you think you are?" directed at myself. Most writing I find chastening. I'm consistently given a reality check by the amount of sheer smarts and talent there is out there.

There are certain writers -- Nick Hornby, for one -- whose work inspires more than intimidates me. Then there are others, like Michael Chabon, who leave me convinced I'm on the wrong path entirely -- that I should turn in my keypad and dig ditches.

That's the thing -- it's the difference between seeing Gene Kelly dance, who makes you think you could do it, and seeing Rudolf Nureyev, who makes you realize you couldn't. It's very, very different.

I'm conscious of it when I read the newspaper. There's a journalist at the New York Times named Charlie LeDuff. He's astonishing. He's like an old-time newspaperman, the kind of people we now read and think, I hope people knew what they had in their presence. I think history will be kind to him.

Before we met, I pictured you as an appealingly acerbic, hard-shelled enigma. I eventually found this to be untrue, of course, and I think that many readers will be pleased at just how much of your gooey center is exposed in the book. Are you ever surprised at how much of yourself you've revealed in your work?

I guess I am; it's that unwitting thing where you really think you're fooling people. But people aren't dumb, certainly not as dumb as one is about oneself. I haven't yet received a lot of reactions, because the book hasn't been out there very long. I haven't yet really heard from folks.

Do you relish hearing from people you don't know?

Sure, if it's in a kind of unmenacing, uncreepy way. If it doesn't involve, you know, hanks of hair and tiny, tiny writing.

Most of the pieces in "Fraud" originated elsewhere but have been revised for the book. Was it a positive experience to revisit work that has had a life of its own for some months or even years?

In the final analysis, sure, it was a positive experience. But when I was doing it? Here's how I like to describe writing: It's like pulling teeth ... out of your dick. The pieces had to become a book, and not just a disparate collection -- they had to somehow mesh. There has to be some sort of arc, and I hope that I successfully managed to create one.

I wonder if the relative boom in humorous essays we're currently experiencing -- in your work and the work of David Sedaris, Sarah Vowell, Sandra Tsing Loh and others -- relates in any way to the recent rise in popularity of the memoir. You each write primarily in the first person; you base your work primarily on events in your lives. Do we, as a society, feel somehow isolated and therefore see these forms as a way of reconnecting with one another?

I view it more negatively than that; I think it's probably the culture of narcissism.

I understand why the narcissist is moved to record the minutiae of his existence, but why do so many opt to read these accounts?

I don't know. I ask myself that every day -- and live in fear of the answer.

So you see the rise of the personal essay and the memoir as a negative development?

I think anything I'm involved in, frankly, should be viewed as a negative development.

Shares