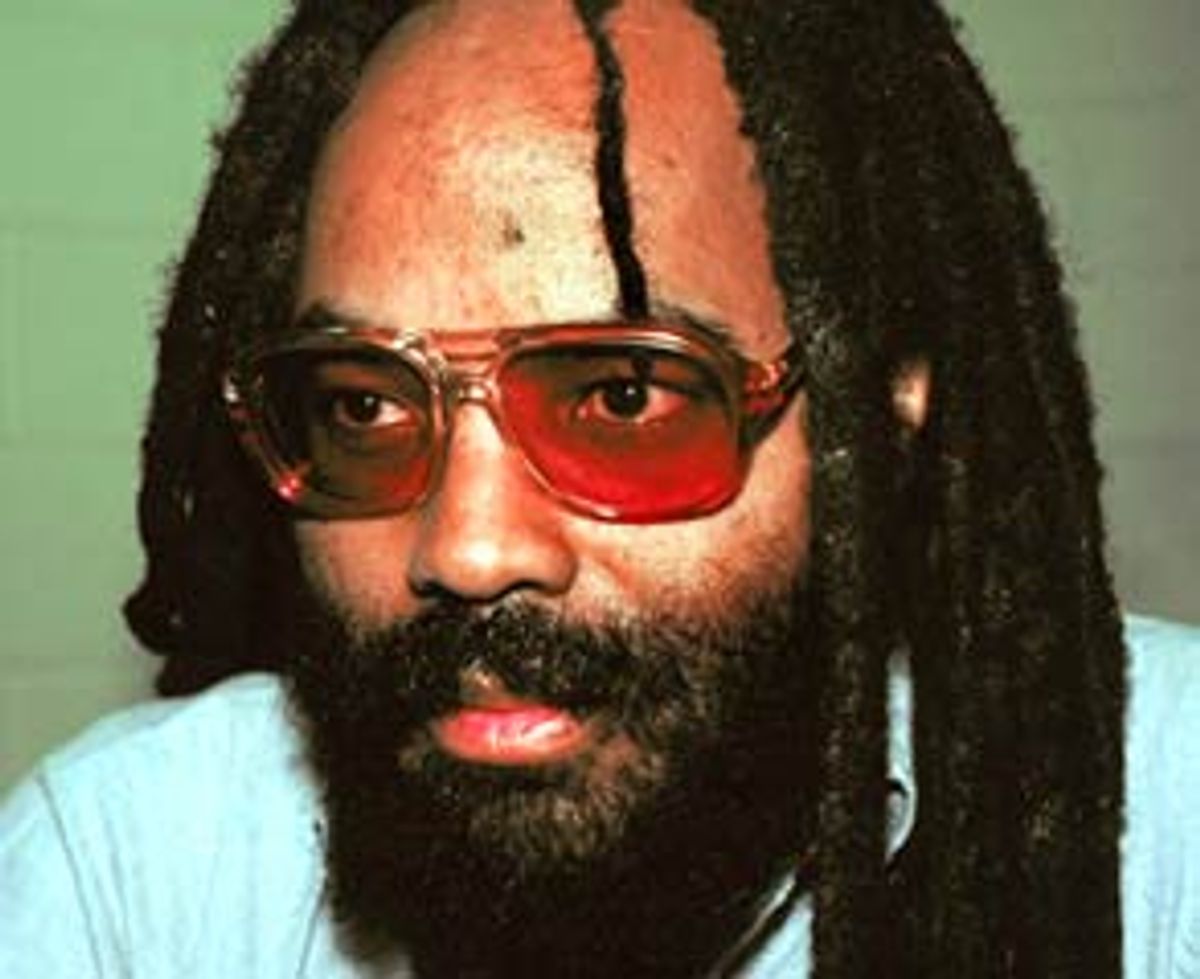

Mumia Abu-Jamal, the black Philadelphia activist and journalist facing execution for the 1981 killing of a police officer, announced in March he was dumping his crack legal team headed by veteran attorney Leonard Weinglass, saying he had lost confidence in it. He has replaced it with two relatively untested newcomers to the complex and technical minefield of death-penalty law, where a single misstep -- whether based on a poorly conceived strategy, or on overconfidence and inexperience -- can be fatal.

Jamal's new legal team joins the case at a crucial moment, as the former Black Panther waits to see whether a federal judge in Philadelphia will agree to hear his last-ditch habeas corpus appeal of his death penalty and conviction on first degree murder charges. After this he has no more automatic right to appeal. It also represents a major shift in strategy. Rather than challenging the fairness of his original trial and subsequent appeals on constitutional grounds, he is now asserting his absolute innocence in the case.

The question on the minds of some longtime Jamal supporters is why this shift is occurring now, just as a federal judge is finally considering his appeal. Some speculate that after spending two decades on death row under almost solitary confinement conditions, already having faced two execution dates, and unable to meet family and friends except while shackled and seated on the other side of a thick plexiglass window, Jamal may have decided on his own not to rely on the appeals arguments developed by his former legal team.

He may instead, this theory goes, have opted for a high-risk political and legal strategy -- a kind of legal "Hail Mary" pass -- with a witness whose mob-hit conspiracy theory, if found credible, would necessarily result in Jamal's being released from prison an innocent man. Indeed, in a recent statement by Jamal which Kamish read at a sparsely-attended two-day encampment at Philadelphia's City Hall on May 12, Jamal tells his supporters, "I have received some criticism for recent changes in my legal team. I don't fear criticism, but I must say I don't agree with this one. You have seen lawyers violate their own rules with total abandon with the blessing of the courts. How can you say you don't believe in the system and then believe lawyers who betrayed their so called client's interests?"

He adds, "I thank you all for joining in this ongoing battle for freedom and justice. And, if you by chance choose not to join me, I have one simple request: don't get in my way."

While that sounds like a confident decision to move forward with a new strategy, it remains difficult to ascertain how much of that confidence is the result of advice received from two attorneys who have been offering him counsel behind the scenes, and behind his prior attorneys' backs, for over a year. Nor is it clear how much Jamal knows about the paucity of trial and death penalty experience of his new legal team. After all, Jamal has little or no independent access to the outside world, and is largely dependent for his information on a handful of people who visit him in prison. A letter sent by express mail to Jamal back in mid-May asking for comment went unanswered.

It's been more than a month now since Marlene Kamish and Eliot Lee Grossman introduced themselves as Jamal's new attorneys at a hastily convened sidewalk press conference May 4 in front of the Philadelphia Federal Courthouse, where they had just entered their names as the attorneys of record in his crucial habeas corpus appeal for a new trial. Grossman is a California lawyer with expertise in international law and discrimination law, not death penalty work, but Kamish is widely credited within the Free Mumia movement as instrumental in getting artist Manuel Salazar off of Illinois' death row in 1995.

Many of Kamish's former colleagues on the Salazar case, however, are openly critical of her work. Though she bills herself (as do her supporters) as crucial to the legal effort that led to Salazar's release, in fact her former boss says she was booted off one of Salazar's legal defense teams, and was only peripheral to another. Attorneys who worked with her also claim she got overinvolved emotionally with Salazar, who like Jamal had been convicted of killing a cop, and that the entanglement led to some bad judgment concerning legal strategy. There were also questions about whether she may have coached witnesses to provide testimony that wasn't entirely correct. In the end, many of her colleagues on that case remember her as a disruptive and negative force.

"She blocked our relationship with our own client," says Karen Shields, Salazar's lead attorney during his initial appeal proceeding, in which Kamish was the third-ranking lawyer on the team for a time. "For some unknown reason, she didn't trust us and made sure that Salazar didn't trust us either. It was all very odd. I cannot understand why she'd want to cut him off from everyone else who wanted to help," says Shields, now a state court judge in Chicago.

Critics suggest that a similar scenario may be playing out in her relationship with and defense of Jamal. For the past 15 months, they note, Kamish has been living in the area around the SCI-Greene maximum security prison where Jamal is incarcerated, reportedly meeting almost daily with the otherwise isolated death row inmate. During this period, she, Grossman and Jamal have apparently decided upon a stunning new defense, based on the testimony of a purported mob hit man. This controversial witness, Arnold Beverly, claims that he, not Jamal, shot Officer Daniel Faulkner on that night in 1981, acting on behalf of corrupt Philly cops. And Jamal, for the first time telling his version of events, corroborates key parts of the supposed hit man's tale -- even though he and his former lawyers earlier decided the alleged mob hit man witness wasn't credible, and rejected using him and his story.

Kamish and Grossman have also publicly criticized Jamal's prior attorneys, accusing them of malpractice and incompetence. In the process they have angered many in the anti-death penalty movement, who view Weinglass especially with near-reverence.

"This area of law is a small circle of people, and we tend to help each other," said a Philadelphia attorney familiar with the case, who noted that it was "unusual and unfortunate" to see new attorneys in a death penalty case attacking their predecessors. "There is no offense taken over a change of counsel, and it's important to have the cooperation of the previous counsel. In this case, though, they seem to have just taken over the files and stopped communicating."

Both Weinglass and Williams confirm that no effort has been made by the new attorneys to contact them for advice or for information about work they might have been doing on the Jamal appeal that had not yet made its way into the court documents and files that were turned over to them.

Repeated efforts to obtain comment from either Kamish or Grossman were unsuccessful. Calls to their offices with specific requests for them to explain their death penalty experience remain unanswered. A third attorney on the team, local counsel J. Michael Farrell, a graduate of Georgetown Law School and a former professor of criminal justice at the University of South Carolina, does have significant death penalty experience at the trial and appellate level, but he says he is "not significantly involved in the case," serving only as the local representative at the court on behalf of the two out-of-state lead attorneys.

Former colleagues, and attorneys familiar with Kamish, who earned her law degree from the Kent School of Law of the Illinois Institute of Technology in 1990, agree she is an excellent organizer and a great investigator -- both important skills in political cases like Jamal's. But they insist she primarily played a peripheral and outside-the-courtroom role in the Salazar case, which involved the fatal shooting of a Joliet police officer.

Andrea Lyon, Kamish's boss at the Capital Resource Center, which was handling Salazar's defense, actually removed Kamish from her role as a liaison attorney at Salazar's Post-Conviction Relief Act hearing -- the second stage of his appeal. "I took her off the case because I was unhappy with the quality of investigation that she did, and I had questions about the way she handled witnesses in the case," says Lyon.

"It's a close call whether you are preparing witnesses or whether you are putting words in their mouths," explains Ron Hayes, the No. 2 attorney in the Salazar case at that time, "and I think Marlene tried to push the envelope farther than she should have," in preparing witnesses for testimony in the PCRA hearing

Several lawyers who worked with Kamish on the Salazar case at one time or another claim that she had become emotionally and personally attached to the client, to the extent that it may have impaired her objectivity. Specifically, several, including Lyon, say that she refused to go along with a legal argument developed by Salazar attorney Hayes, which ultimately led to Salazar's getting a new trial. "She didn't want that argument to be used because she said it would leave Salazar facing a manslaughter charge," recalls Lyon, who is now a law professor at DePaul University Law School and director of the Center for Justice and Capital Cases, and is considered one of the leading women death penalty legal practitioners.

In fact, Hayes' strategy worked. In his retrial, Salazar was convicted of the lesser crime of manslaughter and released for time served (11 years spent on death row).

Lyon's account of Kamish's tenure and her role in the Salazar matter was supported by other lawyers involved in the case, including Hayes and state Associate Judge Karen Shields, who was Salazar's lead appellate attorney during his post-conviction relief hearing.

Like Shields, Hayes believes Kamish sowed doubt in Salazar's mind about his attorneys. "It was very difficult to work with her," he recalls. "Some of her actions alienated the client from us, which is not a good idea in such a serious case. She spent an awful lot of time meeting with and talking with the defendant on the telephone, and she drove a wedge between him and us."

Kamish went on to serve as the third member of the legal team that handled Salazar's appeal before the state Supreme Court, but Charles Hoffman, the lead attorney in that appeal, says of her role, "Let me put it this way: I wrote the brief in that case. The biggest contribution Marlene made is that she got 500 people down to Springfield for oral arguments, and she also managed to get Salazar's paintings exhibited at a museum across the court from the state Supreme Court building during the hearing."

Following the state Supreme Court's overturning of Salazar's original murder conviction, Kamish went on to assist with his subsequent retrial, and helped arrange to bring in lead attorney Milton Grimes, the prominent Los Angeles lawyer who had represented LAPD beating victim Rodney King. But even Grimes insists she played no role in the actual retrial of Salazar.

Recalls Grimes, "She was obsessed with the case -- I'll stay with that word -- and she was helpful outside the courtroom in digging things up, but she didn't interview any of the witnesses." Meanwhile, he adds, "In the courtroom, she irritated and aggravated the hell out of the judge, so part of my job was just trying to bring him back down. She almost made herself more of a negative in the case."

Grimes issued a belated warning, "She had better not start trying to be a trial lawyer in a death penalty case!"

Grossman, while a more experienced attorney than Kamish, also lacks significant experience with death penalty litigation, though attorneys familiar with his legal work say he has some expertise in international law and has handled some anti-discrimination cases. A graduate of Swarthmore College who earned his law degree from Hastings Law School in San Francisco in 1977, Grossman now has offices in San Francisco and Alhambra, Calif.

"I know people who are experts in all different areas of the law," says one National Lawyers Guild attorney in California. "Eliot is not someone whose name would pop up on any of those lists." A Lexis legal search for Grossman turned up no death penalty cases at the trial or appeal level where he acted as an attorney of record, though he is listed, along with Kamish, in a secondary role in the Salazar state Supreme Court appeal, and in the retrial of that case.

Grossman and Kamish are both members of the National Lawyers Guild, an association of radical activist attorneys, and are described by attorneys who know them as dedicated and committed progressive attorneys. Kamish especially is said to be a passionate opponent of the death penalty, and someone who throws herself wholeheartedly into cases she's involved with. She is reportedly a good self-promoter, who has managed to get her name in the paper even on cases like Salazar's where she was not a lead attorney.

But even those who praise her express concern about her very limited trial and death penalty experience. The Illinois Supreme Court's guidelines for death penalty attorneys, for instance, say they should have tried at least eight capital cases -- that is, they should have been on the team that handled those cases -- before they ought to act as lead attorney in a death penalty case.

This would seem to be a poor time for Jamal to be breaking in new lawyers. His case is at a critical juncture, since a habeas corpus appeal to the federal court to review his state conviction is his last guaranteed right to a legal review of his case. Moreover, he has the power of the death-penalty-obsessed, 350-member Philadelphia D.A.'s office and much of the Pennsylvania legal establishment arrayed solidly against him. (Pennsylvania judges, all the way up through the Supreme Court, are elected, many with the endorsement of the Fraternal Order of Police, which has been publicly campaigning for Jamal's execution.)

While federal District Judge William Yohn has the power to order an evidentiary hearing on evidence in Jamal's case, to reexamine the fairness of his original trial and subsequent state appeals, and to order a new trial and/or a penalty phase hearing, he also has the power to reject the appeal. That would leave Jamal with little recourse to prevent his execution by lethal injection -- a result that has been ardently sought not only by the Philadelphia legal establishment, but also by the state's Republican governor, Tom Ridge.

Legal scholars who have examined this internationally famous case disagree about whether Jamal shot Faulkner. But most, including Stuart Taylor of American Lawyer magazine and Amnesty International, are convinced that whatever happened in 1981, he didn't get a fair trial, and that even if he did shoot Faulkner, it was not a premeditated act deserving the death penalty. Jamal's original habeas appeal, written by Weinglass and Williams and the rest of the earlier legal team and now awaiting Yohn's decision, offers several powerful arguments for granting him a new trial, as well as for setting aside his death sentence.

Among these are claims that:

Any one of these arguments, if accepted by the judge, would be sufficient to win Jamal a new trial. But one argument considered by the former Jamal defense team was not used.

That was a claim by a witness named Arnold Beverly, taken in a sworn deposition in June 1999, that he, and not Jamal, actually fired the fatal shot to the forehead that killed Faulkner. In his controversial book "Executing Justice," fired Jamal attorney Dan Williams says that after investigating Beverly's claims, he, Weinglass and Jamal himself concluded that the witness was not credible, and rejected using him in the habeas appeal. That decision led two other Jamal attorneys, Rachel Wolkenstein and Jon Piper, lawyers for the Spartacist League-affiliated Partisan Defense Committee, to quit the case in 1999.

Now, using his new attorneys Kamish and Grossman, Jamal has resurrected the Beverly statement and offered it as evidence of his innocence in a filing with Judge Yohn. Along with that affidavit from Beverly, the two attorneys, at their May 4 press conference, also filed with the court two dramatic sworn statements they had taken from Jamal and his brother Billy Cook, describing for the very first time, in their own words, their version of what happened on the morning of the Faulkner shooting.

The Beverly statement is stunning. Some of it is also pretty hard to believe. The 51-year-old African-American witness claims he was a hit man hired by the Philadelphia Mafia, at the behest of corrupt Philadelphia cops, to execute officer Faulkner, an honest cop feared by his criminal colleagues. Beverly says he and another unidentified person fired the fatal shots into Faulkner, who had stopped Billy Cook's vehicle, and that Jamal, who he says only ran across the street following the shooting, was himself shot by a second uniformed officer after Faulkner was already dead on the pavement. He claims he was helped to escape by another officer, who met him down in the subway tunnel where he ran after the shooting.

In Jamal's own sworn statement -- the first account, sworn or otherwise, that he has ever given of the incident that landed him on Death Row -- he offers support for this new version of the incident, saying that he only ran across the street after hearing shooting, seeing people running and seeing his brother staggering around on the street.

Cook, also making his first public statement on the incident, says he was in his car rummaging around for a registration document at the time he first heard shooting, and then says he saw his brother shot in the street. All three witnesses offer evidence that is significantly at odds with prior testimony by key defense and prosecution witnesses, who, while sometimes mutually contradictory, did tend to agree that they saw either Jamal or someone coming across the street and then heard or saw shooting.

The district attorney's office, which is arguing against the judge's even granting an evidentiary hearing concerning Jamal's habeas petition, has ridiculed the Beverly statement as being "so clearly ridiculous that it should be obvious to any fair-minded person that it is a complete fabrication."

Adding the Beverly testimony to Jamal's habeas appeal, assuming it is permitted, does not in any way erase the other claims made in the appeal drawn up by Weinglass and Williams. But if the judge were to grant an evidentiary hearing, or later, a new trial, the contradictions between what Beverly says happened and what other witnesses said during the original trial and the PCRA hearing could be used to undermine the credibility of other defense witnesses.

On the other hand, that may be a risk Jamal and his new attorneys believe is well worth taking. It could be hard for Yohn to deny at least an evidentiary hearing when he has been presented with a man who says he is the real killer.

Of course, Jamal and his new lead attorneys could always deal with the lack of experience on their team by bringing on a highly experienced death penalty lawyer to help them. The problem, say several death penalty defenders familiar with the case, is that in committing Jamal to a sworn statement concerning the events of Dec. 9, 1981, and filing it as a document with the federal court, they may have already committed several serious legal blunders. If Yohn were to grant an evidentiary hearing, Jamal could now be questioned under oath about his statement -- conceivably even if he refused to take the stand, as he did at his last trial. (A defendant cannot be required to testify against him- or herself, but this constitutional right can be surrendered.)

Lawyers say that if put on the stand, he could be widely questioned by prosecutors, who would only be constrained by having to show some connection between their questions and the facts of his declaration -- a determination that would be up to the judge.

His sworn account can also be used against him to prevent his attorneys from exploring other scenarios of the night Faulkner died -- for example, the oft-cited theory that Faulkner fired the first shot, hitting Jamal in the chest. In the end, there is also the danger that the judge, finding the Beverly claim not credible, could just decide to toss out earlier habeas claims.

Jamal's new attorneys also opened the door to having both Jamal's prior lead attorney, Weinglass, as well as Billy Cook's attorney, Daniel Alva, called to the stand to be questioned about their advice to their clients. This is because at the press conference, Kamish and Grossman made claims (and allowed Jamal and Cook to state in their sworn affidavits) that Weinglass had advised both men not to testify during Jamal's PCRA hearing in 1995, and subsequently. (In fact, the PCRA transcript shows that Alva told the court in 1995 that Weinglass had asked him to have Cook appear to testify, and Weinglass told the court he expected the brother to appear, but Cook never showed up at the hearing.)

Ironically, fired attorney Williams may end up saving Jamal from the problems created by his new attorneys' legal strategy. That's because the district attorney's office in mid-May actually cited information in Williams' book to buttress its claim that the Beverly testimony should not be used. In a brief filed with the court in late May, D.A. Hugh Burns argues against a defense request that the judge order his office to take a deposition from Beverly. As part of that brief, Burns quoted from a section of Williams' book in which he discusses the defense team's 1999 decision not to use Beverly, calling the alleged hit man's testimony "patently outrageous."

In the end, Williams wrote, Jamal himself rejected using it because he was "far too honorable to propagate a lie upon which to build a case for his freedom." If the D.A. is successful in blocking the Beverly testimony, that would prevent its being used to discredit other possible scenarios the defense and Jamal supporters have long suggested to explain his actions and Faulkner's death.

Kamish and Grossman have also stumbled in handling the public relations aspect of their high-profile case. At their May 4 press conference, when asked by reporters why the Beverly evidence was only being disclosed and used in court now, nearly two years after it was discovered by the defense, they said they "didn't know," and said they had "just found it in with the documents received" from the previous attorneys in the case. Since this account was demonstrably false, the local press was quick to note that in fact the Beverly evidence had been rejected by Jamal and his legal team back in 1999 -- something that the new lawyers clearly had to or should have known.

The new defense team also released a transcript of a polygraph exam of Beverly conducted in 1999, a document they have also attempted to add to the habeas file. The test would appear to show Beverly was telling the truth, but the defense failed to mention that it was only one of two tests conducted -- and that another was less positive. They also failed to note that the test in question had been known to Jamal back in 1999 when he decided against using Beverly's testimony as part of his habeas appeal.

Jamal's stated reason for firing his prior legal team was that he felt betrayed by Dan Williams, whose book included accounts of the inner workings of the defense, including the dispute over whether or not to make use of the Beverly affidavit. But his dissatisfaction with his legal team clearly went beyond just the book and Williams, as evidenced by his firing of Weinglass, too, who had nothing to do with the book, and who in fact criticized Williams for publishing it without Jamal's express approval.

Firing Weinglass, the lead attorney in the case, and several secondary attorneys too, suggests not so much a loss of confidence in them as a profound decision to alter the strategy of the case, making it more of a frontal attack on the legal system itself, instead of simply an effort to find constitutional errors in the original trial or subsequent appeals that might overturn the results.

Jamal's new legal strategy poses a tough challenge to the international movement that has grown up over the years to campaign for Jamal's freedom. There has always been a tension in that movement. On the one side are the true believers who are convinced of Jamal's absolute innocence and his wrongful conviction, incarceration and sentencing. On the other are those who have taken a less absolutist view of the case, arguing instead that Jamal, confronted with a clearly pro-prosecution judge, an inept and overworked attorney (Anthony Jackson), and with prosecutorial misconduct, never had a fair trial in the first place, or a fair appeals process.

In fact, one of the signal successes of the Free Mumia movement over the years had been its success in linking support for Jamal to broader opposition to the death penalty. While death penalty opponents can always be counted on to offer at least token support for anyone facing execution (even Timothy McVeigh had people protesting his execution), going with the current strategy could risk losing some of the enthusiasm that had made Jamal something of a symbol of the national and international campaign to abolish capital punishment in the U.S. Clearly, many of his supporters will be uncomfortable with a conspiracy theory that, while portraying Jamal as wholly innocent of killing Faulkner, also requires a belief in a cluster of implausible events: that Jamal just happened to be on the scene of a police rub-out; that corrupt police would risk hiring a lowlife mob hit man to kill a fellow officer on a public street; and that those same murderous cops would then help that hit man to escape so he could live to later betray them.

It is significant that at the May 12-13 encampment rally for Jamal in the shadow of Philadelphia's City Hall, the crowd was small and the speakers appeared to be almost entirely true believers in Jamal's innocence. Many, citing Beverly's confession to Faulkner's murder, demanded that Jamal be released immediately, not simply retried for the shooting. Meanwhile Kamish, a small, intense but soft-spoken woman, made an impassioned plea for the May 12 crowd to "free Mumia," saying, "This is the last opportunity for Mumia to be in court as a right. This moment in time is the time that we must free Mumia."

Calling her role as defense attorney "an awesome honor and privilege," Kamish said, "Attorneys should be accountable for their actions and I want to be accountable."

Shares