One night I was sitting with a youngish Norwegian customer, enjoying a break from the near-constant horniness of the older Japanese men, when he suddenly nodded his head toward Louise, a British hostess. "She's very good," he whispered, his eyes filled with wonder and admiration.

I looked over at Louise. That night she had arrived with the customer we called "the Cowboy," given his penchant for droning country and western songs all night long. (Hank Williams and Patsy Cline were his favorites.) He was in the middle of "Crazy" and Louise, her hands on his shoulders, was gazing at the Cowboy in ecstatic adoration, or some perfect imitation of it.

"The way she looks at him, she looks like she's completely in love with him," my customer said in a hushed voice. "She's a very good hostess."

She was. The ability to fake love may be the hostess's most important skill. Every girl at Verdor had a minimum of one or two serious customers who either accompanied her to the club after dinner or came to meet her there on a regular basis. It wasn't hard to keep track of which customer was whose, and what he came for. Amanda's best customer was a slave to her bullying and strong intelligence; Tara's patrons were wild about her golden beauty and prima ballerina hauteur; Elise's men loved her singing voice.

A hostess has to identify her strengths and play off them, because the competition is stiff. Most clubs are notorious for fur-flying catfights, where kittenish women battle it out for customers among the fast-draining supply. Japan is, after all, in a recession, and things are getting harder for everyone.

As the weeks went by and I realized that my mama-san, Midori, fired girls who couldn't trick customers into falling for them quickly enough, I became puzzled. I didn't understand how I had succeeded where other girls had failed. (When I was an 8-year-old Girl Scout I had been voted, on a camping trip, "the hostess with the mostest" for my skills at ushering in girls at mealtime, but that couldn't have been prophetic.)

My customers enjoyed talking about literature and appreciated my sincere interest in Japanese culture and karaoke. But I still didn't understand what they were looking for in me.

I asked Mr. Kobayashi, a consultant and former politician, why he preferred me, and he replied, "When we men come here, we come to take part in a fairy tale. You believe in that fairy tale."

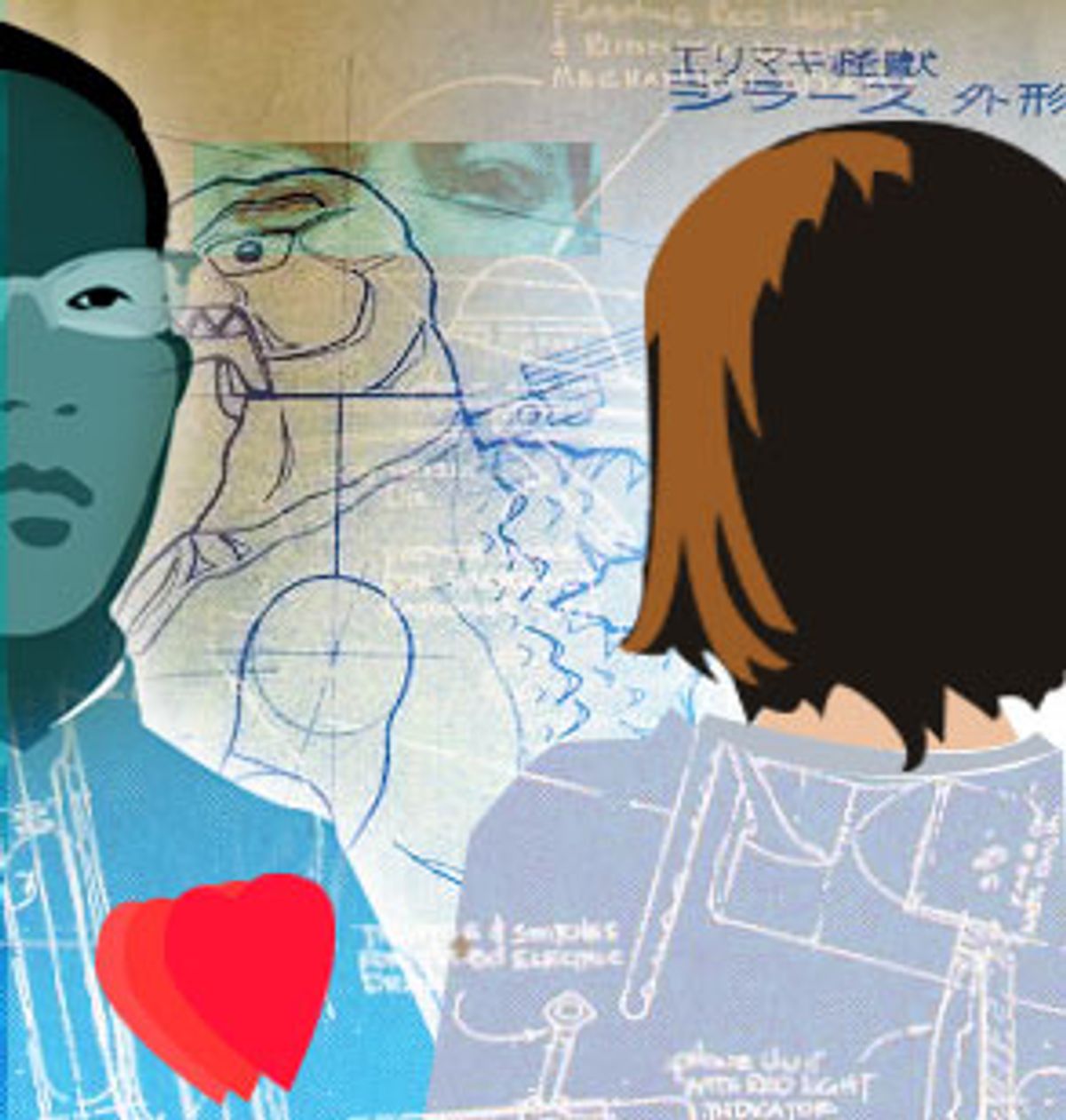

He had hit on something. It was true that, as a bit of a dreamer, I did relish being part of a fantasy: donning a foreign persona (the ideal beloved, the fatal temptress, the dream woman) and leaving reality at home. That is what I thought the "floating world" was all about.

And in some ways it is a fairy tale. For a few hours, an aging man -- most of the regulars were over 50 -- gets to spend time with a lovely young woman, with no complications in sight. For a few hours, the woman is paid to act as if she adores him. In this situation, even the typical lack of sex could be considered an advantage, because it makes for a more idealized, more aestheticized affair.

Being somewhat of a perfectionist, I took my new occupation more seriously than I probably ought to have taken it. In the beginning, at least, I strove to be an impeccable companion. I remember the heart palpitations that overtook me the first time I went out to dinner with a customer before work -- my first douhan, Mr. Mori. Arriving at work on the arm of your patron was, in theory, kind of like entering a ballroom with a gorgeous date; all the other girls who had come to work unaccompanied would look over enviously, and you could hold your head higher, basking in Midori's approving smile.

In reality, however, you were probably already drunk on champagne (your customer having gotten a jump-start on making you tipsy) and already sick of his highly limited conversation (most men talked about work, the weather and sex -- and little else). One of the advantages of having a devoted patron, however, is that his talk tends to be a little less smutty than that of occasional customers who come to carouse with their drinking buddies. After all, serious customers really do want you to like them.

The serious ones take you to the best restaurants in Tokyo -- or at least what they consider the best. I've been treated to dinner at exquisite and intimate restaurants that serve steak made from the famous hand-massaged, beer-fed Kobe cows. But I've also been taken to some very odd places, like a members-only restaurant where everything is high class, from the well-trained waiters and beautiful furniture to the foie gras, except that the waitresses are dressed like Playboy bunnies. (I can't seem to get away from them.)

Usually, if she has a douhan, a hostess will meet her customer around 6 or 7 for a leisurely dinner before they go to the club together. This is the expected plan. I've rarely heard of a customer asking a girl to dinner on a weeknight and then flatly refusing to accompany her to her club afterward, though some men do try to get out of this expensive part of the bargain. After dinner it's usually enough to just lightly take the customer's arm and tell the cabdriver to head toward Akasaka -- and he acquiesces. You both have roles to play.

It's the woman's job to figure out how to burrow so deeply into her customer's heart that she will not be dislodged, no matter what he has to pay to be entertained by her or how many leggy foreign girls flash smiles at him. Hostesses do this in a variety of ways. Sandra, for instance, strengthened the bond with her clumsiest customer by asking him to take social dance lessons with her on Saturdays. Amanda, a true dominatrix, constantly sent her customers firm and witty e-mails, literally demanding their company at the club.

I received instruction on how to care for Mr. Suzuki, one of my fans, from Midori herself. "He likes to be yelled at," she told me.

"Really?"

"Yes, yes -- slam the phone down on him when he calls you. He'll come to the club that night."

I tried this, and it worked. This wasn't the art of love, it was the art of war.

In this game of manipulation you have to make fast decisions. If a love-struck customer shows up at the club while you're with another "suitor," you have to play it right, perhaps by faking a tantrum while the first customer is in the restroom, demanding to the waiter that he switch your seating in tones loud enough for the second man to overhear. With the first man, however, you still have to act sweet and fascinated -- you can't let either one suspect your faithlessness.

Sometimes girls have to make changes in their personality and outward level of intelligence, maybe even adjusting their fluency in Japanese. Less is sometimes more, and some men prefer to talk to girls they perceive to be dumb. Others, however, enjoy wide-ranging conversations about their favorite topics -- current affairs, travel, history, literature -- and hostesses sometimes bone up on customers' pet subjects in an attempt to impress them. When you talk to a customer, it is also important to make your life sound exciting -- and to never talk about bills or mundane worries or your "real" love relationships.

Keeping the conversation rolling and acting "genki" (or lively) are key to success as a hostess. After all, you're supposed to be more interesting than the women the men see on a daily basis -- their girlfriends or their wives. In their minds, they always have room for one more woman.

Despite the obvious insincerity of the "love" for sale in such an environment, many customers do fall for their favorite hostess and expect their feelings to be reciprocated -- never mind whether their age is two or three times that of the girl.

All my fellow hostesses had that problem -- customers who believed that the girl they paid so handsomely to drink and dine with them was a girlfriend. Of course, we each fed those hopes. A hostess plays a strung-out game involving that most ancient question: Will she or won't she? Her job is to get as much money as possible out of the customer before he realizes that she won't. At that time, he might move on to another girl or simply abandon that club altogether. Still, many customers hang in there month after month, with a resigned attitude and an open checkbook.

These rather desperate fantasies become more explicable when you consider the cultural environment. Throughout Japanese literature and aesthetics, the preferred kind of love is one marked by poignant sadness -- the unrequited desire, the dying bride, the lovers who have no chance to be together except through double suicide. Seen in this light, the "floating world" of geisha and hostess clubs may be desirable because of the very impossibility of true love within it.

Still, to really make this fantasy work, the hostess has to be either a calculating bitch or something of a dreamer -- maybe a little of both. She has to get something out of it, and if money isn't the only thing she cares about, then she has to, at some level, emotionally value her customers' worship of her. I know I did; in a way, this false love was addictive.

I looked forward to seeing my customers' faces light up when I met them at restaurants before work; I went out of my way to look attractive so that my appearance would reflect well on them. That, after all, was a great part of what they were paying for. I did my best to entertain them with talk and flattery and singing, since I wanted to justify their regard for me, especially when they saw such a limited part of me.

Other women had more serious problems with love and its fakery. Sherry, one co-worker, fell in love with a 40-year-old married customer, only to have him drop her for Louise, another hostess at Verdor. She lost both him and the money she had made before and while he was her boyfriend. (She saw him outside of work for free during their affair, but he continued to meet her at the club as a paying customer.) For weeks afterward she had to force back tears as he fawned over his new girlfriend at the next table. By the time I left Verdor he was already flirting with a third hostess.

Like this playboy, a hostess is likely to be juggling several customers at once, but she has to be careful to appear neither too popular nor too desperate. To do well in the business, it's best to have two or three serious patrons at any given time. But avoiding collisions -- two customers at the club at once, for instance -- is like running an obstacle course in high heels. You have to come across as faithful, even though everyone knows that it's your job to not be.

Part 5: Hostesses, wives and co-workers.

Shares