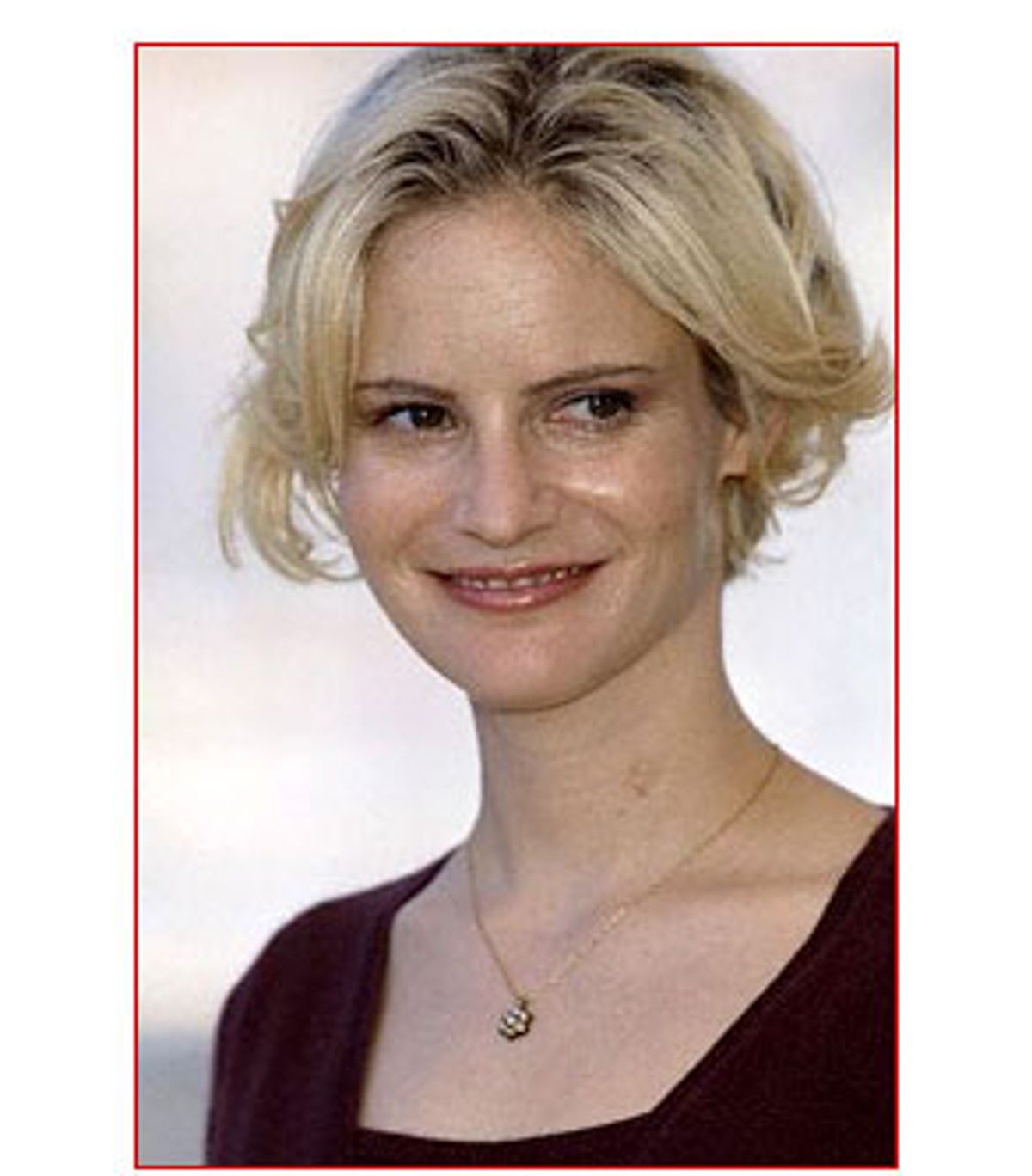

Jennifer Jason Leigh is a celluloid changeling, able to morph herself into a gun moll, a heroin addict or Dorothy Parker with aplomb. Now, Leigh, 39, hankers after the role of auteur. And if her freshman effort "The Anniversary Party" is any indication of what she's capable of, then the critics might as well pony up that particular laurel on bended knee.

"The Anniversary Party," which Leigh wrote, produced and directed with Scottish man-child Alan Cumming, flows before us with great economy of movement -- as if the two have performed this dance countless times before. They play a successful Hollywood husband and wife on the occasion of their sixth wedding anniversary. The party's on, and their pals are all invited. But Sally (Leigh) and Joe (Cumming) have just reunited after a painful separation, and their soiree's pregnant with a bellyful of disaster.

The film, cast with Leigh and Cumming's friends and shot in a glass house (metaphor alert) in the Hollywood Hills, is trenchant, sexy and tragic all at the same time -- a movie for grown-ups. Recently, Leigh discussed "The Anniversary Party" over a glass of iced tea.

"The Anniversary Party" reminded me of a good Robert Altman film. You've worked with Altman before -- has he been an influence on you?

He's been a huge influence my whole life, my whole career -- and [John] Cassavetes and Woody Allen. They've all made a mark. But certainly Altman in terms of how to make actors feel safe and welcomed. When you're working on an Altman film or an Alan Rudolph film, there's no place you'd rather be. There's so much trust and freedom that it's an absolute pleasure. So that's something that I understood firsthand, those experiences.

What did you do to put the cast at ease?

I cast friends. Everyone's playing friends, but they actually are all friends. I think on a certain level the film works because there's this real familiarity between people. We had no motor homes. Everyone would come to work and get made up at the same makeup tables. We had really good food. The women who played America and Rosa (the housekeepers) cooked these incredible gourmet breakfasts every morning. Then we'd go to the set and work all day. When they weren't working, people were hanging out on the lawn or sleeping in hammocks. Kevin Kline would play piano, and Michael Panes would accompany him on violin. It was an extraordinary experience.

Was everything scripted in the film?

Yes, but there was a little improvisation in the scene where Alan and I are toasted. I sat down with all the actors and talked about the characters' relationships to each other and things that they might know about us and want to talk about. We asked them to go off and write it so we'd have the experience of being surprised, and hearing it for the first time. And they would have the experience of giving it to us for the first time.

In the segment where everyone's doing charades, that was scripted, but to get to that state of heightened frenzy and aggression we had each actor go through the entire charade, and everyone was allowed to throw things in and go through the clue to its completion. Then in the editing room, we edited it back down to exactly what we had scripted. That gave it a life force it wouldn't have had otherwise.

The film also made me think of "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?"

Yes, that's our kind of humor, that's what we love. In fact, [John Benjamin] Hickey and I once read through "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" together when we were doing "Cabaret." It's such great writing. I love that kind of brutal, scathing humor. That's something I'm definitely drawn to.

How did the collaboration with Alan Cumming come about?

Alan and I were hanging out with each other after our time in "Cabaret." I had just finished being in "The King Is Alive," which was shot using digital video, and I told him how exhilarating it was, as an actor, to work like that. And how cheap it was. We were both talking about how we wanted to direct, and we thought we'd do it together -- write about something we care about, and write for our friends.

We started with who we wanted to be in it, and began to play with it. It just kept growing and growing. Then we started pitching it. We sold it to Fine Line, and then we had to write a script. By that time we had talked about it so much that we knew every scene very well. Then it was just a matter of writing and rewriting.

How did you make that work, co-directing with Cumming?

Alan and I were really on the same wavelength. I guess we were lucky in that we share a lot of the same tastes and opinions, and we had this incredible intuitive understanding of each other. That helped a great deal.

We were also very disciplined. We only had 19 days to shoot, and ended up with 40 hours of footage. On "The King Is Alive," which also used digital video equipment, they had 120 hours of footage. It took them a month just to make the selects of the dailies. We had a budget of $3.5 million, so that forced us to be sparing in how many takes we did. Usually we did three, working with three of these state-of-the-art digital video cameras.

You thank your mom, screenwriter Barbara Turner, in the credits. How did she help you?

Oh, she was enormously helpful. She was our harshest critic on the script and helped us make it sharper, funnier and smarter. That's why it says "A big 'less words' thanks to Barbara Turner," because she kept saying to us, "Less words. Less words."

I know you're a private person, and you've expressed your distaste in the past with publicity. Did that make exposing your personal life as you do in this film painful?

It's like what Alan's character says in the movie about his book: "It's a novel." You draw on stuff that's personal. But that's the great thing about it. As an actor you're always doing that, you're just doing it with someone else's words. To do it as a filmmaker is really incredible. The only time you feel exposed at all is talking about it --like right now. But actually creating the work is the most enlivening, enjoyable and gratifying thing. There's nothing else like it.

Where's the line between your character, Sally, and yourself?

There are many things that are similar, but many things that are different. When this first came about I was going through a breakup and trying to recover from that. All my creative energy went into things that had to do with breakups, getting back together or both. You become the most creative during the saddest times. It's also a time where you reach out to friends a lot. So it was such a perfect thing, this film -- and it came together easily because of that.

What appealed to you about a party being the catalyst for an investigation of relationships?

I like the idea of something taking place within a 24-hour period and all that can happen in that 24-hour period. A party symbolizes life and fun and hope and joy. The fact that it can completely derail and undermine this relationship it's supposed to be celebrating is inherently funny and truthful to me.

Your character has a lot of issues with marriage and with the possibility of having children.

She's in total denial about it because she's so hopeful. She's willing to completely efface herself for this marriage. She's willing to uproot herself and move to London because that's where her husband is happiest. She wants to be anything he needs her to be, so she can hold on to this marriage. Also, they're both at that point, in their 30s, at which they have to decide whether they're going to have children or not, and if they do, what that means for their work.

How does that apply to you, since you're in your 30s?

I'd love to have children, and I think marriage is great, I really do. This movie examines all kinds of marriages. We examine so many almost microscopically. They're all kind of flawed but they work. And there's something beautiful about that. We know that every marriage in this movie has gone through some horrific nights and somehow managed. So maybe Sally and Joe will make it. I wanted to leave that as a question in the viewer's mind.

Your film addresses the creeping paranoia people feel in Hollywood over the subject of aging, especially women. Why was it important for you to satirize that?

Not only are we satirizing Hollywood, we're also indicting it. It's a true thing about women aging in Hollywood -- that suddenly there are no parts. But that's the great thing about this movie: There are lots of great women's roles. And that's an exciting thing to bring to the table. I plan to write and direct more good parts for women, myself included.

Yet everyone in the film is lying about their age.

Yeah, even the youngest woman in the film lies about her age. But Kevin's character lies about his age too. It's the nature of the business. People equate success with youth. And if you haven't had a certain amount of success by a certain time in your life, it's never going to happen. There's a fear about that. So people start lying about their age really young. I've never done that because I think it's so insignificant. You are the age that you are, no matter what you say, and you look the age that you look. That's why I can poke fun at it, because I don't feel threatened by it.

Do you and Cumming plan to direct together again?

Oh, yes. I think Alan will do one on his own and I'll do one on my own, then we'll come back and do one together.

What draws you to the darker roles you're known for?

Happier characters are usually pretty dull, unless they're very funny and well written. The darker ones -- like in "Georgia" or "Mrs. Parker" -- are better parts. They're more dynamic and challenging. I care more about them because their lives are so hard. But they're really courageous in the way that they live. There's something vulnerable and naked and daring about them. That's what makes playing them more satisfying.

Some reviewers have said, "Oh, Leigh will never get an Oscar because what she does is too edgy." Do those sorts of comments piss you off?

No, we joke about that in the film. For me it's, like, can I keep working? That's where my joy is.

Shares