The greatest show in Tokyo is on the street, a crowded asphalt catwalk where, on weekends, fashion is all about fuzz and cuteness and Barbie and pinkness, a gorgeous perversion of American niche culture that takes in cheerleading, ghetto glamour, Catholic school and the high-pop aesthetic of every decade in teen, 'tween and 20-something memory -- namely the '60s, the '70s and the '80s.

The greatest program for the greatest show is Fruits, a magazine created in 1996 by photographer Shoichi Aoki as a means of documenting the street fashion scene. The slick portfolio focuses mainly on the Harajuku district of Tokyo, ground zero for a street chic movement with its own factions, labels, inspirations and subcultures. (There are, for example, the Wa-mono, who combine traditional kimono and obi with wacky Western elements; the cyber kids, who reference technology and UFOs in their gear and lean toward bright primary colors; and the secondhand fashion look, which is all about vintage and thrift, carefully mismatched for maximum migraine potential.)

And now, Aoki's greatest portraits of the city's funkiest kids, taken from Fruits magazine, have been collected into a book, also called "Fruits," published recently by Phaidon Press.

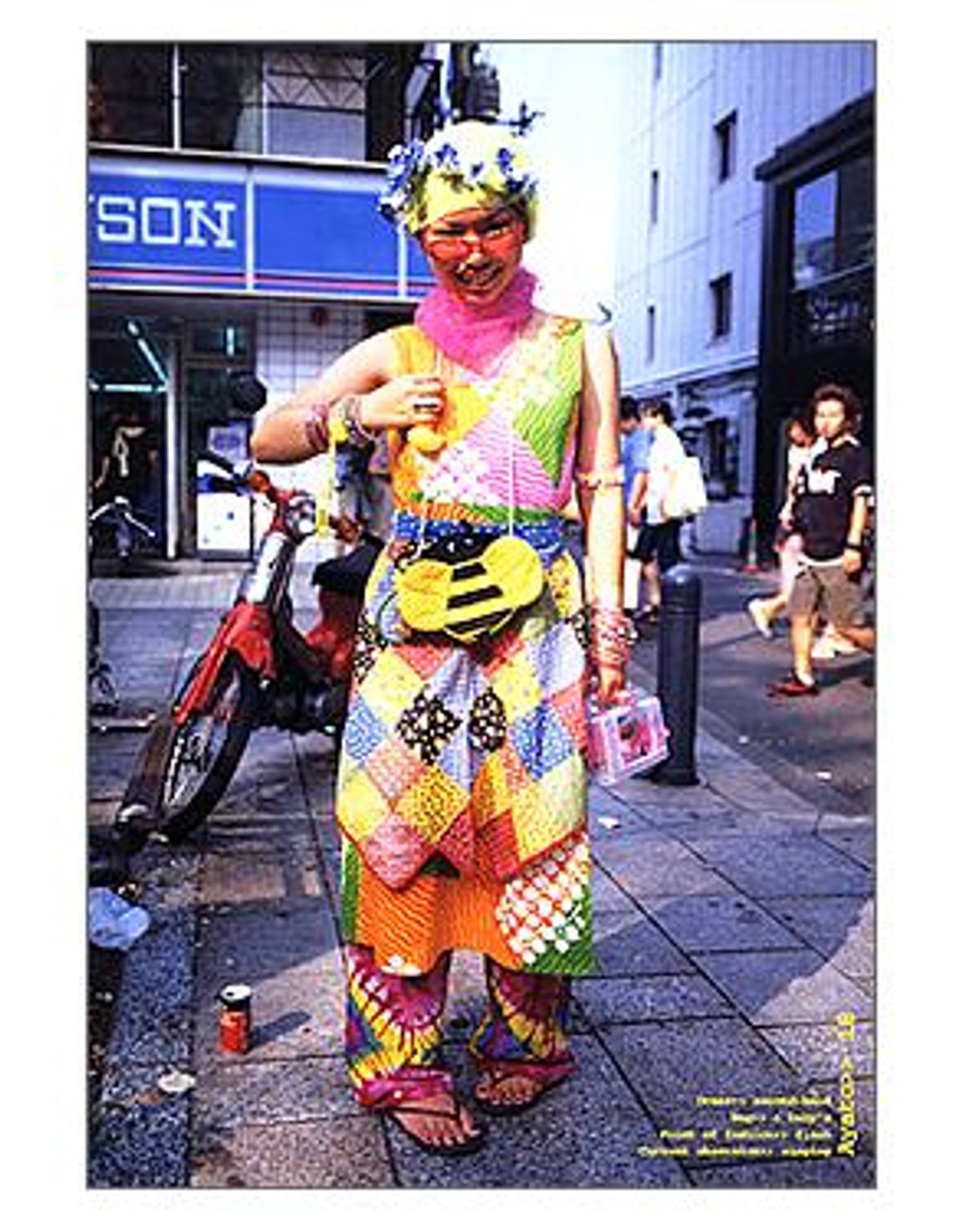

"Fruits" has no real narrative. Each page consists of a full-length portrait of one or more kids (mostly teens and college kids) looking right at the camera. Each subject is identified by first name and age, along with a short description of where the outfit came from, fashion references (or "point of fashion") and current obsessions. Inspirations include such far-ranging bizarrity as Goa, various Japanese cartoon characters, "American High School," "sexpot," "cyber-blue," the "Pink Panther," "sweet bacteria," fairies," "sticker syndrome," "onion hair" and -- my personal favorite -- the "elegant gothic Lolita" (which, believe it or not, is an entire subgenre of the movement).

It's difficult, with mere words, to accurately describe the outfits that go with these descriptors. Needless to say, these ensembles include nothing as mundane as a mere top, bottom and shoes; they are costumes, usually with multiple coordinated layers, bags, props, hairstyles, stuffed animals and, if you've really got it together, a friend to match.

Take, for example, 18-year-olds Heri and Tehe, who describe their point of fashion as "matching each other." Both sport ratty knit ponchos in vibrant geometric patterns, over pastel floral dresses, red tights and black Mary Janes (the latter from their high school uniforms); with yarn-woven braids and oversize sunglasses. They look like mutant refugees from 1976; with the sweet faces of babies, but clothes that suggest the sexually liberated grunge of a post-hippie commune.

Or there's Mai and Neh, both 16, who boast miniature plaid aprons over coordinated pastel T-shirts, petticoats and button-down shirts; one in pink, the other in blue. The shoes are platform; the hair, pink; and the accessories, cumbersome -- Mai, for example, has strung around her neck a Snoopy doll, a snorkel mask, an inflatable teddy bear and a plastic cellphone.

This demure look would probably be best described as Kogaru, which is a popular Lolita-esque look based on the 14-year-old Japanese anime character Sailor Moon, who has taken Japan by storm in the last year.

Girls who prefer a more adult (or, at least, postpubescent) look tend to gravitate toward the equally popular Ganguro look, in which girls blacken their faces with self-tanning lotion, cake on white eye shadow and lipstick, and complete the look with enormously tall platforms and micro-miniskirts. But Aoki has a talented eye for picking out the truly unique fashion statements, as opposed to the kids who are merely copping the latest trend; and while Kogaru and Ganguro make appearances in the book, the total impression of "Fruits" is far more colorful and diverse than a litany of lookalikes.

There are, for example, punk rockers who favor vintage Vivienne Westwood and prominent facial piercings; the aforementioned "American High School"-inspired boy, who wears a tight, fitted, striped jacket with matching shorts, white platform boots and a red pencil case strapped around his thigh (a look from which most American boys would run screaming); one purple-haired student in a head-to-toe leopard-skin suit, and the "elegant gothic Lolitas" in their demure black-and-white dresses, elaborately braided hair, and matching parasols and lace hats. There are cowgirls, alien visitors, neo-hippies, 1984-era Madonna lookalikes, "rockers" with inflatable ukuleles, and lots and lots of stuffed animals.

Aoki chooses not to speculate about the motivation of his photo subjects, which is fine with me. Yes, it could be a youthful backlash against conservative culture that encourages conformity. It might be the claustrophobia of Tokyo city life: When you live in an apartment the size of a shoebox, the streets become a theater simply because there's nowhere else to hang. Maybe it's feminism. Maybe it's fantasy. Or maybe it's simply an updated version of the dramatic external decoration that drives Kabuki theater or geisha culture.

Regardless, "Fruits" manages, without words, to serve as a Technicolor admonishment to Westerners in their bland uniforms of logo-studded Gap T-shirts, Levis and Nike tennies. Where is the imagination in lock-step replication and mindless conformity? Where is the fun in Easy Spirit pumps? What makes us think we need vast sums to make strong statements?

And finally: Where can I get an inflatable ukulele for cheap?

Shares