John Ford is to America what Rudyard Kipling is to England: a constant reminder of our past sins and triumphs, a consummate craftsman and professional hack, a flag-waver who keeps nudging us, if not about the white man's burden, then at least about our responsibilities as the masters of Manifest Destiny. George Orwell wrote that Kipling produced "good bad poems ... capable of giving true pleasure to people who can see clearly what is wrong with them." Orwell could have been writing about Ford's films. I once asked the director Jim Sheridan what it was like to grow up in Ireland and watch "The Quiet Man" on TV.

"My family would gather round the TV," said Sheridan, "and watch. We couldn't watch the bloody thing without cringing." So what was the verdict? He shrugged. "We cringed. And we watched."

I can't think of a more appropriate reaction to Ford's oeuvre. How can an intelligent person be expected to react to the thick, rich blend of sentimentality, brutality, chauvinism and homilies in Ford's films -- including, among the major titles, "The Informer," "Drums Along The Mohawk," "Young Mr. Lincoln," "Stagecoach," "How Green Was My Valley," "My Darling Clementine," "They Were Expendable," "Fort Apache," "She Wore A Yellow Ribbon," "The Searchers" and, of course, "The Quiet Man" -- without cringing at least a little? Yet I don't know how 20th century film can be studied without putting Ford up front. Who else could qualify as nostalgic poster boy for the Republican Party while also having been the favorite filmmaker of Joseph Stalin? How is it possible for us not to respond to the man that Orson Welles considered our greatest director?

John Martin Feeney -- he later claimed to have been born Sean Aloysius O'Fearna in order to seem even more Irish, as if that were necessary -- was born in Maine in 1895. A liar of insane proportion, he padded his bio with an imaginary high school diploma as well as college educations from schools he never attended, and he claimed to have gone on spy missions for the Irish Republican Army and the U.S. government -- stories that contained more fiction than his films. Ford broke into the movies in the silent era when many directors (William Desmond, Allan Dwan, William Wellman, Raoul Walsh) were Irish, but as Scott Eyman puts it, Ford was "the only one to play the professional Irishman." It was a role that lasted a lifetime.

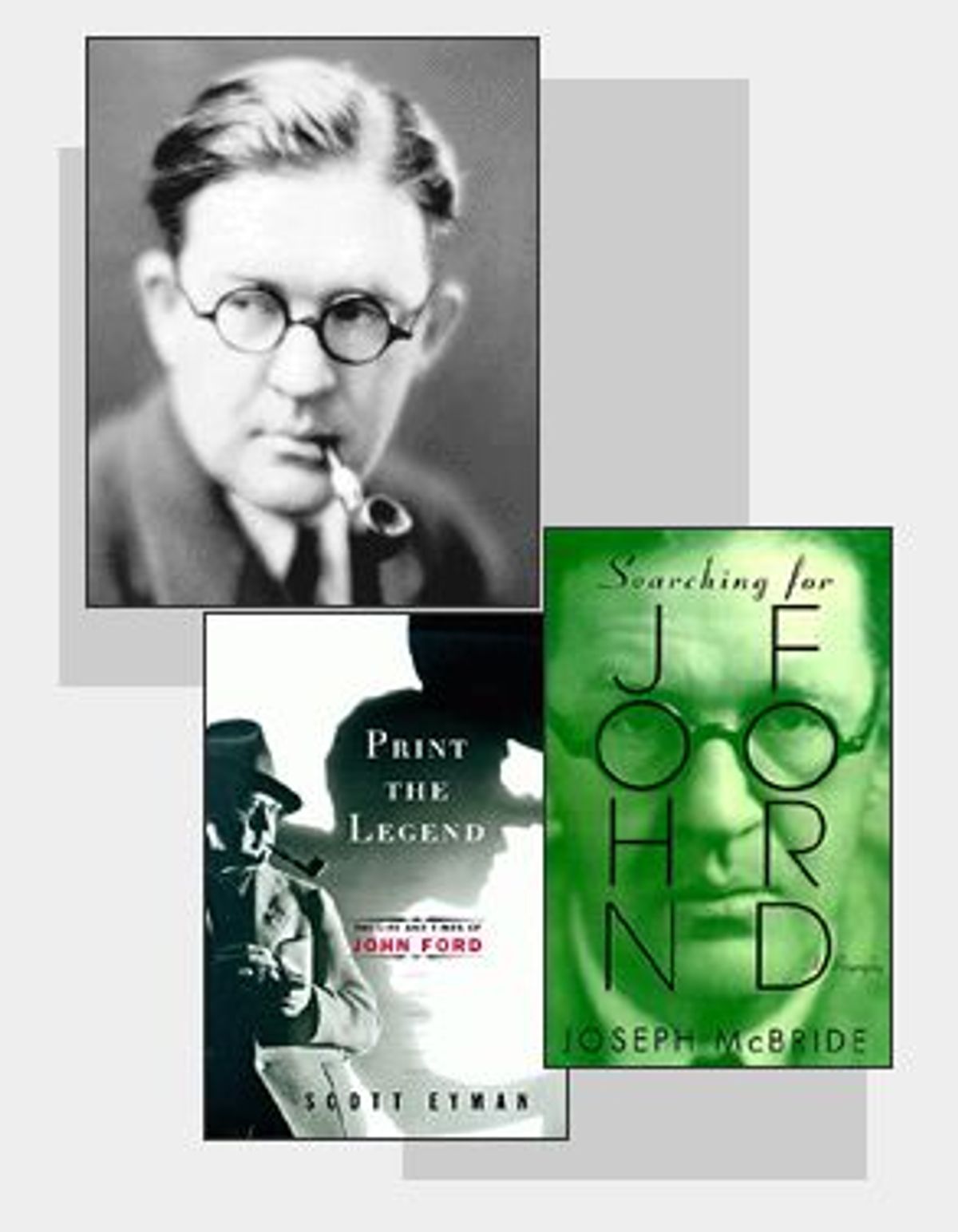

That lifetime has now filled two massive volumes: Eyman's "Print the Legend" (originally published to great critical acclaim by Simon & Schuster two years ago and now available in paperback) and Joseph McBride's "Searching For John Ford," just out from St. Martin's Press. Both succeed as biography and criticism better than any book that has preceded them, but unfortunately they also contain much of the same information regarding Ford's life and loves. (Both, for example, examine Ford's legendary infatuation with the young Katharine Hepburn, and both shy away from actually declaring it a physical relationship). Eyman and McBride will tell you pretty much all you could want to know about the man, and both will make you glad you never had to work for him.

Though it's clear that both authors end up with a grudging admiration for Ford, most others will find him a monster; indeed, most of the people who knew him found him to be one. Pandro S. Berman, a producer who worked with Ford, called him "about the meanest man I ever met." To a young actress in an early film he was "an S.O.B., a demonic man. Part of his mercurial personality was to do something he knew was mean or mischievous, then try to justify it." His son Patrick probably summed Ford up best when he called him "A lousy father ... but a good movie director and a good American."

Both Eyman and McBride relate the story of a character actor named Frank Baker who came to Ford begging for money when his wife was in the hospital; Ford screamed at Baker, publicly humiliating him, and then punched him. Then he sent a man to see that Baker's hospital bills were taken care of, proving once again that sentimentality is often found on the other side of the same counterfeit coin as brutality. (It would be a more satisfying story if Baker had come back and thrown the money in Ford's face).

Ford's favorite victim was John Wayne, who knew he had no career without Ford and so endured years of being derided as a draft dodger (which he was, for all intents and purposes; though legally exempt from conscription due to his age and marital status, Wayne repeatedly found excuses not to enlist because it would have hurt his career) and being told that he "walked like a fairy." On more than one occasion, Ford actually sent the most popular male star and movie tough guy in history scurrying off the set in tears. (If you've always hated Wayne, these stories alone are worth the price of the books.)

Politically, Ford was a man of violent contradictions, with the operative word being "violent." While having the guts to make the most popular left-leaning film of pre-World War II Hollywood, "The Grapes Of Wrath," and to defy his Commie-hunting friend Cecil B. DeMille during the McCarthy era, Ford nonetheless embraced a rabid right-wing attitude in the '50s and on through the Vietnam War era.

A monster, yes, and a monster of contradictions, but a fascinating character to read about. (Will any of today's TV-raised, film school-bred directors make movies and lead lives interesting enough to inspire books like these?) McBride has had the terrible bad fortune to have been working on the same great idea at the same time as Eyman, and to have lost out in the Ford biography race by more than a year, but in truth, "Print the Legend" deserves the wider readership even if both books had been published at the same time. Eyman gets to the truth in a hurry and focuses on it; McBride, no doubt trying hard to justify the second enormous book on Ford in two years, pads.

There's an awful lot of information in "Searching For John Ford," but some of it seems quite unnecessary and some of it seems forced and rushed. "I visited Tombstone, Arizona," he tells us, "studying the actual topography of the so-called gunfight at the O.K. Corral, so I could better understand how Ford transformed the sordid real-life story of Wyatt Earp into the grandly romantic Western mythology of "My Darling Clementine." Why bother? Ford's movie isn't set in Tombstone but in Monument Valley in northern Arizona. (It must also be said that McBride botches the complex story of Earp and the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, and though he lists my own book, "Inventing Wyatt Earp," in his bibliography, he does not appear to have read it.)

In his effort to distinguish his book, McBride has blurred the lines between biography and criticism to the advantage of neither. "What has been lacking in previous books about Ford," he writes, a bit too self-servingly, "has been a real understanding of how his life and work are interconnected. Discovering how Ford's great films emerged from his jealously guarded inner life is the object of this biographical search."

But of course such an effort is doomed to failure, since no amount of research or psychological analysis can ever tell you why Ford and not a dozen other directors could take B-movie material like "Stagecoach" and make it into one of the most watchable movies ever made. The idea that anyone's life and work are "interconnected," at least to the degree that the life can explain the quality of the work, has long been discredited in literature. (Does anyone still believe that knowing the real-life counterpart of every character in a Fitzgerald or Faulkner novel really leads to a greater sense of artistic appreciation?) And it doesn't help that McBride's critical analyses of the films often end not in illumination but in hyperbole, as when he calls Ford "the closest equivalent we have had to a homegrown Shakespeare" or when he claims that Ford constructed scenes "in a quasi-Brechtian fashion," a phrase that should surely be struck down any and every place it appears.

If McBride sometimes lurches precariously between roles as biographer and critic, he fails completely to appreciate the line between critic and fan. For instance, in defending the appalling "Irish humor" interludes in Ford's films (invariably involving Victor McLaglen), McBride argues that "the same kind of humor" is accepted in Shakespeare's comic relief, so why not Ford's? The critic in him should have answered: "Because in Shakespeare it's funny," or, at the very least, "We love Shakespeare in spite of such things and not because of them." (Every time I see an example of Ford's "Irish humor" I remember Flann O'Brien's remark about "a virulent outbreak of Paddyism.")

And McBride, like all Ford apologists, wastes entirely too much time struggling with the question of how a man who could "use" Indians to terrify viewers in "Stagecoach" could then have been so sympathetic to them in "Cheyenne Autumn." "There is, in fact," he writes, "no simple answer to this question." I'm not so sure about that, and I'd like a crack at it. I think when Ford wanted to excite people with a spectacular chase scene he was happy to use Indians or anyone else without a qualm, and when he gave himself over to sincerity he was simplistic and sentimental about Indians and other minorities. I should also add that the exploitative Ford made much better movies than the "fair" one.

In the end, if we are going to read and try to enjoy books on filmmakers such as John Ford we must do so for what their scholarship can tell us about the nuts and bolts of how the movies were made and for the fun of glancing behind the scenes of films we've seen dozens of times. On that score McBride does quite well indeed, showing, say, how the unrelenting give-and-take between Ford and producer Darryl F. Zanuck, lovingly recounted in "Searching for John Ford," probably produced greater films than either man made separately.

"Searching For John Ford" would be a much better book, though, if McBride didn't try so relentlessly to reconcile and explain the seemingly contradictory forces in John Ford's character and work. Better to simply adopt a Whitmanesque attitude towards the man. Did he contradict himself? Very well, then, he contradicted himself. So we cringe, and we watch. But we watch.

Shares