"Hello! Make yourself at home."

The old man, scrawny and as tough as a strip of jerky, popped up from an unseen corner of the desert. He had the leathery, chapped look of a fair-skinned man who had fried himself crispy in the unfiltered sun. His hair was an indeterminate color, maybe straw, maybe gray, and it lay in spiky clumps like a jester's cap. But his eyes were a clear cornflower blue -- a startling color against the earth tones all around.

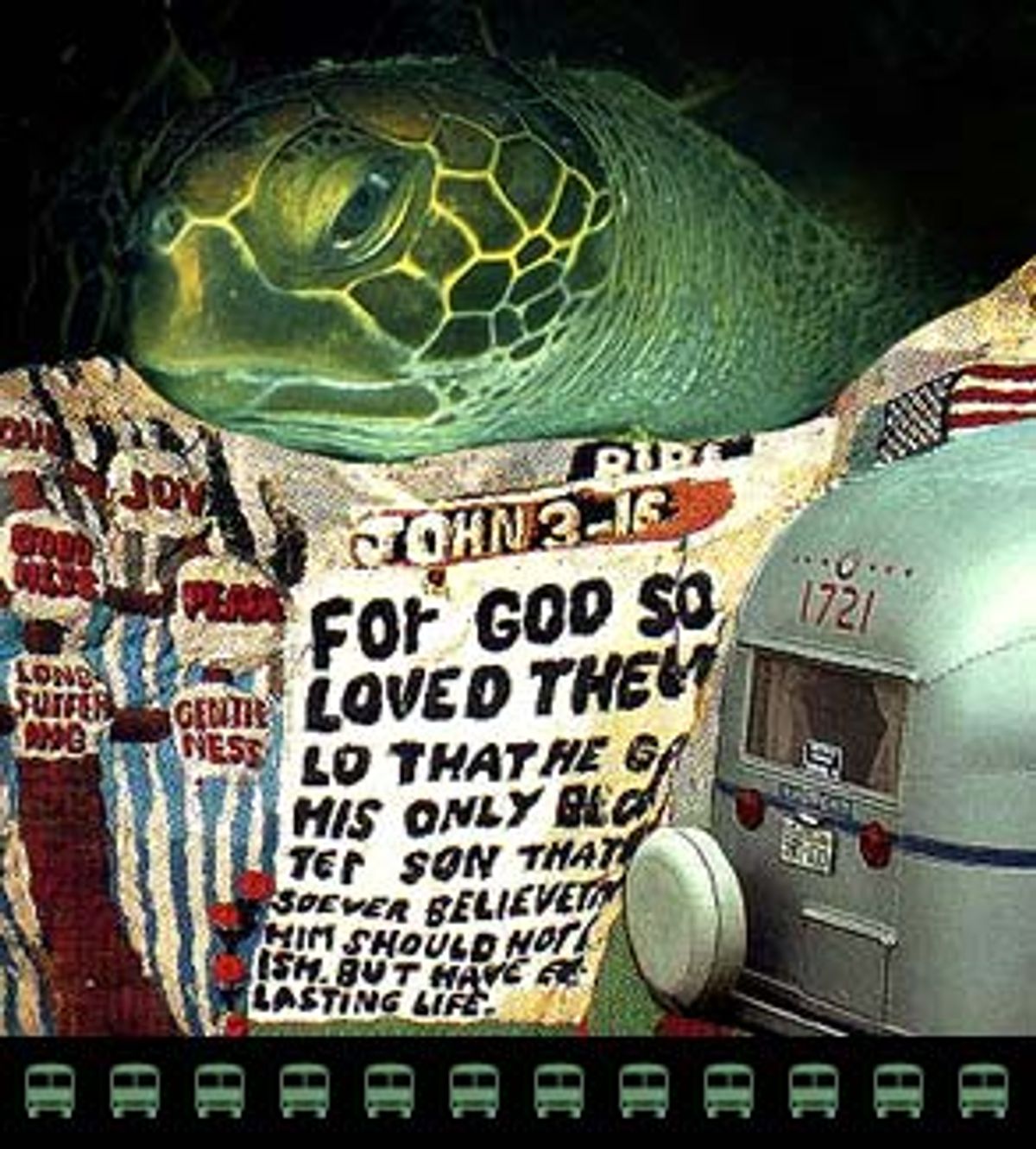

It was hard to tell what Leonard Knight meant by "home" or how, exactly, we should make ourselves comfortable there. Looming behind him was a modest mountain that was painted like a giant, garish birthday cake. The entire mountain was festooned with flowers, ablaze with Bible quotes, stippled with stripes. Slick and tipsy yellow-painted steps led to its summit, upon which a 12-foot white cross perched like a birthday candle.

On the face of the mountain was a 15-foot red heart with white lettering that read: "Jesus, I'm a sinner. Please come upon my body and into my heart." This is Knight's canticle, his life song. It is the message he received 30 years ago when God fell upon his head and spun his life around. He has labored ever since in brave and foolish ways to carry the message he received to the world.

Knight lives on the outskirts of Slab City. ("Turn right at the second grocery store in town and follow the road out to the desert," we were told.) Slab City is an odd phenomenon, a sprawling tumor of wheeled dwellings in the Southern California desert. And Leonard Knight is a prince among eccentrics. He was passing through Slab City some 15 years ago, puzzling about how God wanted him to spread the word, when his truck broke down.

"Folks here were nice to me," he says, and he discovered that the mountain directly behind his truck was made of clay. Knight heard the voice of God and went to work. With a shovel and a wheelbarrow he dug up the surface of the mountain and mixed it with straw to make adobe, then he formed and painted his mountain.

Knight is 69 years old and moves with the agility of a young man. He dwells with his cat in the truck that brought him to the mountain. (It is running now.) He lives on little, asks for nothing and apparently has all he needs to stay alive and pursue his opus. He says his most important donation, although he does not ask for them, came from a little girl who gave him 50 cents. "I wanted a pop," she said, "but I wanted to give this to you more."

The vision that has sustained him through all the years of solitary, backbreaking labor is to "get the message out. I want to put God's love out into the world. I want the whole world to look at this mountain and say, 'Boy, that's simple.'"

And the crazy thing? The deep karmic belly laugh? It worked. Knight's mountain has become an internationally known example of "outsider art" -- the whimsical, sometimes obsessive, often strangely beautiful work created by untrained people who would not think to call themselves artists. Knight's mountain has been featured in a Japanese coffee-table book and on a BBC television program and in a scrapbookful of national press. I heard about him at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore.

None of this fazes Knight. He continues to work on his mountain, which grows more intricate and colorful as the years pass. He will patiently answer questions with the candor of a child, but he is more interested in welcoming newcomers than in holding court with interviewers. "Excuse me," he says, darting around a corner. "Hello!" I hear him say. "Make yourselves at home."

I have always pictured prophets as monoliths -- patriarchs with cosmic messages, the Charlton Heston kind of message accompanied by choirs and thunderclaps. I am finding that a road trip is strangely suited to meeting cranks as well as visionaries, and I have met both. The prophets, however, are easy to recognize. They have a sense of direction; they carry a message that is larger than themselves. It can be whispered as well as shouted, lived -- or painted on a mountain -- as well as spoken. Prophets, I think, are common people to whom the scent of God clings in uncommon ways. But most important, the qualities they all seem to share are passion, simplicity and joy.

To me, the most impressive thing about Leonard Knight is not his mountain. It is the spirit of the man himself. He does not preach or evangelize. He does not even belong to a formal church. He simply welcomes strangers and lives his message with all his heart. He is the sweet instrument through whom the message plays.

Heather Paige heard an entirely different melody. She is a rumpled version of the California girl she once was. She is tan, blond, competent and tightly wound. When she first stumbled upon the Tortuga Project in Baja California, Mexico, however, she was lost.

The Tortuga Project is the love child of another pair of visionaries, biologists Antonio and Beatrice Resendiz, who have devoted their professional and much of their personal lives to studying sea turtles. They have lived for many years in a remote fishing village on the pristine shore of Bahia de Los Angeles, a bay of warm, sapphire water in the Sea of Cortez where sea turtles, seals, whales, sharks, dolphins and a host of water birds dwarf the human population.

When Paige stumbled upon the Tortuga Project, she was working as a graphic designer in San Francisco. She had the right look, the right attitude, the right income, a promising future and a very nice car (Alfa Romeo). But during her stay the visions came with disturbing insistence. One night Paige wandered over to the tanks that hold the ancient sea creatures awaiting release. In a darkness lit by an infinity of stars, she lay on the side of a tank and listened to the intermittent breathing of the turtles. "It was the most beautiful, peaceful sound, the turtles breathing at night," she said.

By the time Paige returned to San Francisco, she had experienced a conversion as profound as Leonard Knight's. She sold or gave away everything she owned. Handing back to her father the key to his house, she said, "You know, Dad, this is my last key. And that's the greatest feeling in the world."

Almost a decade later, we, too, set out to find the Tortuga Project. We wandered, as lost as Paige must have been, among the Mexican-style jumble of palm-thatched palapas, tumbledown dwellings and apparently abandoned buildings. The gaggle of adolescents we eventually found clustered around the turtle tanks, however, was joltingly familiar. We had expected to find almost anything in that remote and magical place except middle school students from California.

This is Paige's doing, her vision made flesh. As co-founder of One World Workforce, she organizes tours for Americans who want to visit research projects like this one. In the decade since she listened to the nighttime breathing of the turtles, One World Workforce has become a respected ecotourism outfit that brings workers, exposure and potential donors to projects that struggle for funds and recognition in obscure places.

Paige recently bought a used pickup truck, her first possession in many years. She is content with the course she took, although sometimes the demons visit in the dark of night. "I live like a vagabond," she said. "Every now and then, I get this funny feeling that I'm kind of a loser because I'm not like everybody else."

Prophets and dreamers are not like everyone else. That's why they have been laughed at and locked in institutions since Homo began to consider himself sapiens. Maybe that's why I've discovered more of them as I travel to out-of-the-way places. Prophets sometimes live next door, but I suspect that mortgages and utility bills tend to stifle visions.

Shares