Like its title character, TNT's original movie "James Dean" is sad and sexy, riveting and beautiful. In a trim two hours, director Mark Rydell, screenwriter Israel Horovitz and actor James Franco deliver a tender portrait of a troubled genius, and they manage to do it without TV movie triteness or creepy necrophilia.

In his first two movies, "East of Eden" and "Rebel Without a Cause" (he only made one other film, "Giant," before dying in a car wreck at 24), James Dean's powerful, alluring vulnerability brought out something sensually maternal in leading ladies Julie Harris and Natalie Wood. And "James Dean" falls for the soft-spoken actor with the same protective ardor. This is a movie that wraps its arms around its subject; if it can't soothe the pain, at least it can let us see how deep it ran and how brilliantly Dean turned it into art.

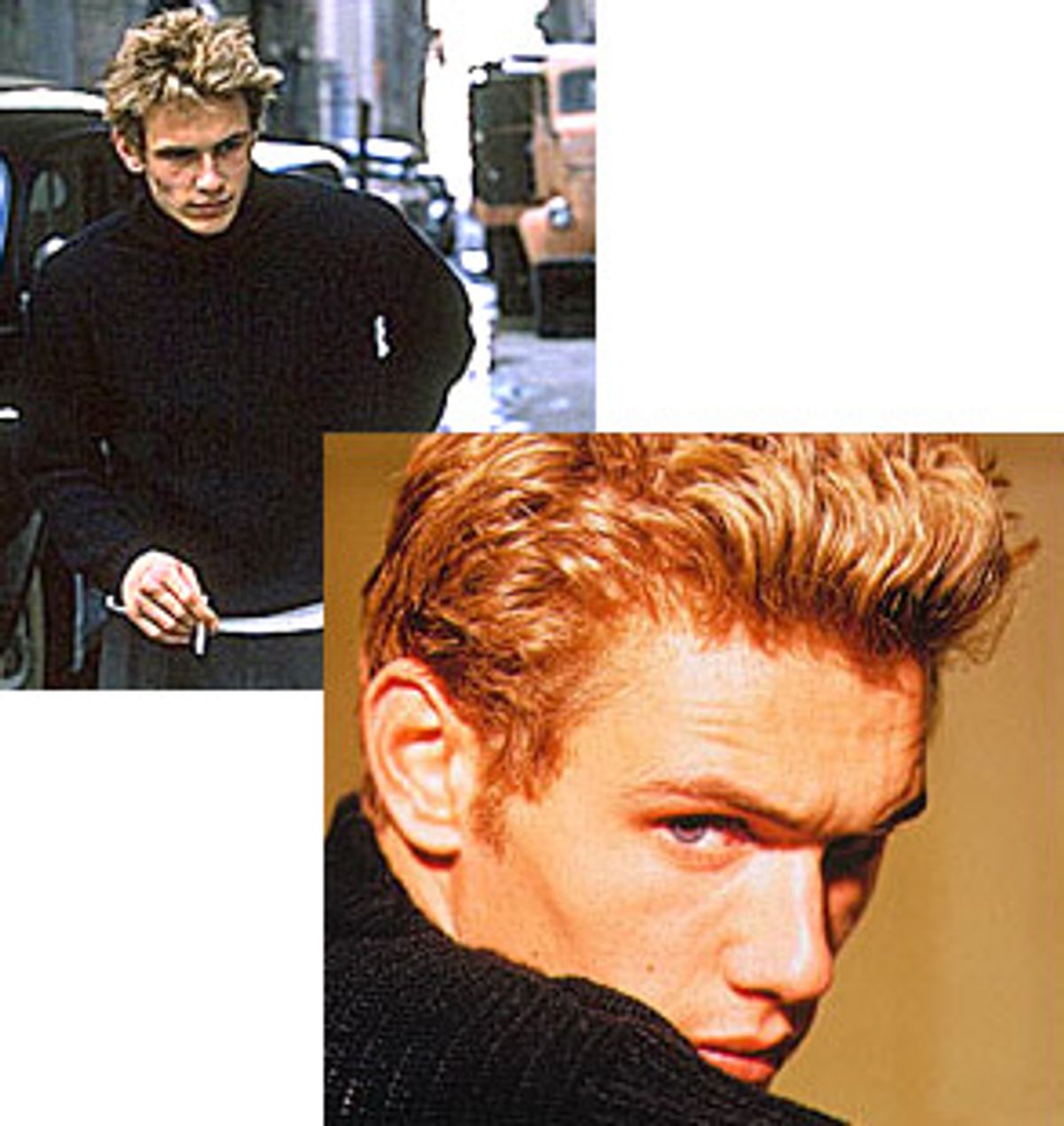

Rydell (who knew Dean when they were both students at New York's Actors Studio in the early '50s) and playwright Horovitz have been planning a James Dean biopic for years; Johnny Depp, Brad Pitt and Leonardo DiCaprio were all mentioned for the lead at one time or another. James Franco, who finally won the role, is hardly a household name -- unless your household regularly watched NBC's too-short-lived "Freaks and Geeks." If so, you know that Franco played Daniel Desario, the misunderstod "freak," or stoner, who struggled with secret shame over his bad reputation and poor grades.

Daniel just wanted to get an education and escape from his dead-end life with his sickly father, unemployed brother and bitter mother (in one episode, she taunts him for being "the oldest junior in Michigan"). But adults pegged him as a delinquent. In the series' final episode, Daniel gets busted by guidance counselor Mr. Rosso in the act of setting off a fire alarm; desperate to improve his grades, Daniel was trying to postpone a test he hadn't studied for. Rosso doesn't ask for an explanation, he only mocks him ("Do you think you're the Fonz?"). Daniel replies wearily, "No, sir," but the guidance counselor is only prepared to hear insolence.

Daniel Desario is, of course, a descendant of James Dean -- or rather, of Cal Trask and Jim Stark, the misunderstood teens Dean played in "East of Eden" and "Rebel Without a Cause" (which were both released in 1955, the latter posthumously). James Dean defined modern teenage pain and angst as we know it. And "East of Eden" (directed by Elia Kazan) and "Rebel Without a Cause" (directed by Nicholas Ray) marked a cultural shift in attitudes toward adolescence, which until then had been depicted in movies as just peachy-keen.

Dean's teenagers were emotionally complicated boy-men who vibrated with the promise of dark sexuality and the threat of darker violence. In "East of Eden," an adaptation of John Steinbeck's Cain and Abel tale, Dean's Cal, the "bad" brother, is rejected by his father in favor of the "good" Aron. But it's Cal who becomes the hero at the end. And in "Rebel Without a Cause," we're encouraged to sympathize with Jim and his street-racing, knife-fighting pals, whose anger and alienation are portrayed as the result of bad (or indifferent) parenting.

Franco's wonderfully shaded work in "Freaks and Geeks" was the perfect tuneup to play James Dean. But even those of us who suspected that Franco had a great performance in him couldn't have imagined it would be this great. Franco's Dean doesn't rest on mimicry and makeup, though he has the sharp cheekbones and the slim-hipped slouch to pull it off. Like Judy Davis in her shattering turn as Judy Garland in the recent ABC miniseries, Franco anchors his performance in his subject's childhood trauma. Dean (like Garland) found that he could channel his misery and loneliness into art. But Dean went even further, imprinting his pain on the characters he played, identifying so closely with them that, finally, the line between acting and life was hopelessly, tantalizingly, blurred. He was the ultimate Method actor.

"James Dean" opens with a splendid scene set during the filming of "East of Eden" that nails how out of step the decidedly quirky Dean was with old Hollywood, and how persuasively and cannily he would play Pied Piper in leading movie acting into the new world. On the first day of filming, Dean, wearing Coke-bottle glasses (he had terrible eyesight) and tootling a tune on a recorder, walks up to the straitlaced, rather grand Raymond Massey (Edward Herrmann), who is playing Cal's disapproving father, and gives him a long sizing up. Then he turns to director Elia Kazan (Enrico Colantoni) and drawls, "He can't play my father, he's too old. Get somebody else." When Kazan corners him and tells him he has insulted the great Raymond Massey, Dean replies quietly, "Good. I need him to hate me."

Apparently, Dean succeeded. His Method quirkiness reportedly got under Massey's skin, and nowhere is this more apparent than in the film's climactic birthday party scene. Here, the sullen and underachieving Cal, who has been rejected time and again by his Bible-quoting, stiff-necked farmer father, Adam Trask, suffers a final, devastating rejection. To win his father's love, Cal has devised a scheme to make back the money Adam lost in a failed business venture. Cal has made secret investments in bean futures that have paid off with the coming of World War I; he hands his father a wad of bills, but Adam refuses to accept money made on the war. Dean makes Cal go almost limp; he lurches toward Massey's Adam, clings to the embarrassed man, but Adam won't return the embrace. Then, Cal rushes out the front door crying like a wounded animal.

Franco is astonishing in the "James Dean" re-creation of this scene. Every inflection, every move, is right. But this is not mere imitation -- through Franco, you feel as though you're seeing the inner workings of Dean's performance. Between takes, Franco's Dean is in a sort of trance; after Cal exits and Kazan yells "Cut!" we see Dean alone in a dark corner of the set, hunched over, hugging his knees and crying. Franco and the filmmakers capture the overwhelming enormity of Dean's effort to summon this performance, his utter emotional nakedness.

That's a helluva downbeat way to open a movie about the American legend who was "too fast to live, too young to die, bye-bye," as the Eagles so breezily sang in their facile number "James Dean." But, wait, "James Dean" gets sadder. Cut to bespectacled James at 9 years old, reciting a poem he has carefully memorized for his father, Winton (Michael Moriarty). Winton icily tells the kid to get lost, he's reading the newspaper. James is an artistic boy, encouraged by his mother, Mildred (she gave him the middle name "Byron" after the poet), and the emotionally desiccated Winton doesn't want any part of him. Soon, James' mother dies (the flashback scenes are golden-hued and wisely fleeting), and Winton puts the boy and the coffin on a train back to Indiana to live with relatives. James sits by the coffin, telling his mother, "I'm right here." Horovitz and Rydell theorize that the loss of his loving mother and his subsequent futile efforts to please his aloof father coalesced into the pain Dean carried with him all his short life. It's the pain that made him great.

Obviously, "James Dean" is more interested in tracing the psychological roots of Dean's awesome artistry than in adding to the towering Dean mythology. "James Dean" depicts only one of the actor's (supposed many) Hollywood romances, his rocky, Romeo-and-Juliet affair with the starlet Pier Angeli (Valentina Cervi). As for the bisexuality rumors, there's one brief scene where Dean, a starving acting student in New York, is hit on by a director who promises him an audition if he stops by his place around midnight. We see Dean knocking on the door and being let in, and that's that. But the suggestion is clear: Dean, whose angular beauty, boyish energy and unfettered kookiness charmed friends of both sexes, was ambitious enough to do what it took to get a break.

"James Dean" also suggests that Dean was willing to exploit not just body but soul to produce the desired result. In a scene depicting his interview with Kazan during the casting of "East of Eden," Dean pulls out a pocketknife and toys with it as he talks about his mother's death and his father's withholding of affection: "Well, we don't really talk much. We don't like each other. Fact is, we hate each other." Where does Dean end and Cal begin?

But, then, that was the Method, the shock of the new. And while Kazan and Ray championed him and saw him as an artist, not a puppet, studio despot Jack Warner (played by Rydell, looking like a scary, oiled rat) didn't know quite how to deal with this strange, fragile new star who was beyond his control. "I love you and I hate you," Warner chuckles, at a party celebrating Dean's million-dollar contract with Warner Bros. "I hate you, and I hate you," Dean replies, with a big smile.

Warner also ordered Dean to stop racing his Porsche Spyder, but we know how that turned out. "It was a beautiful, clear day," Franco's softly twanged voice-over tells us as Dean sets out for one final drive in the Spyder.

Look, I know this beyond-the-grave narration sounds hokey and spooky, but it isn't. It gives "James Dean" something your basic "A&E Biography" profile doesn't have -- a point of view. It's Dean's point of view, and it pulls us into the story. It also mirrors the way Dean keeps speaking to us through his few performances and the emotions that fueled them, even though he's been dead for almost 50 years.

Watch him at his most wrenching in "East of Eden," playing a confused 17-year-old in 1917 Salinas, Calif. In the opening scene, he's dressed in a white sweater that's almost too small for him and flared flannel pants; he looks like an overgrown little boy. He has found his long-lost mother (his father told him she was dead) and he's spying on her, following her through the Monterey waterfront to the whorehouse she owns. Dean, who was 22 when the movie was made, moves like a teenager in this long, silent scene, slinking along with his hands in his pockets, then rushing headlong, almost out of control, waving his arms to keep his balance. His eyes are hurt yet hopeful; he wants to reach out to his mother; he wants to know who he is and why his father can't accept him. He makes Cal's longing to be loved and noticed, as well as his impulsive cruelty toward his favored brother, not just contemporary but timeless.

In his spectacular, heartfelt performance, Franco walks Dean's walk and feels his pain. And we feel that pain, too, or, rather, our version of it. The particulars may be different for each of us, but the ache of it is familiar and true; it was James Dean's gift to the freaks and geeks of the future.

Shares