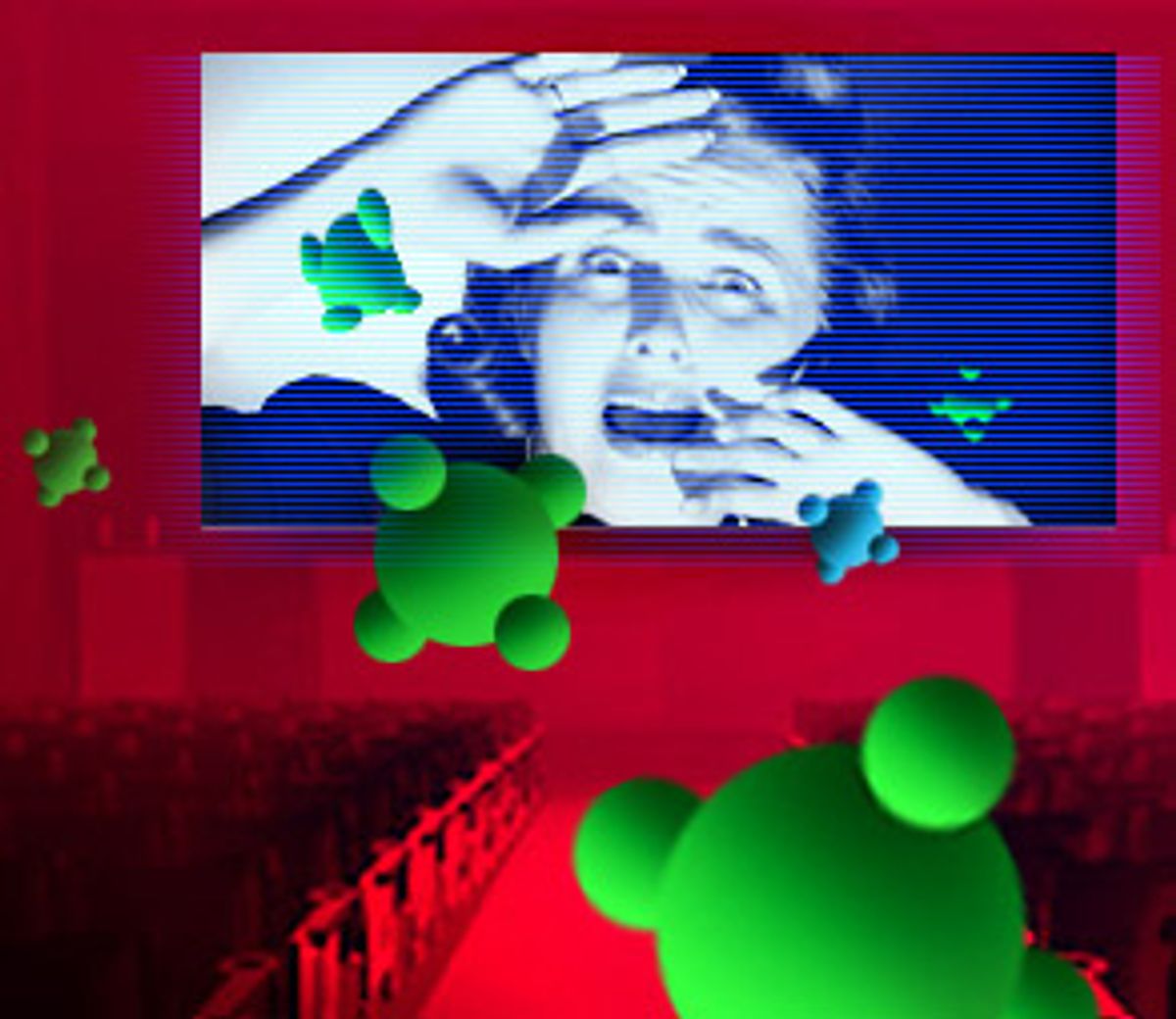

Just as atom bomb anxiety infused Cold War-era pop culture, virus anxiety -- in the form of plagues, epidemics, parasites and microbe-caused mutations -- permeates recent pop culture. In "World War III" -- a bloody, made-for-TV movie broadcast last month on Fox, Russian terrorists release an airborne virus that kills almost 200,000 Americans. In Ivan Reitman's lame comedy "Evolution," an alien microbe outbreak threatens the extinction of humanity. Advertised as an "infectious comedy," the Farrelly brothers' new half-live-action, half-animated "Osmosis Jones" is set inside the infected body of a construction worker (Bill Murray), in which a deadly virus (Laurence Fishburne) battles it out with a street-smart white blood cell, Osmosis Jones (Chris Rock).

While the latter two movies try to wring nervous, gross-out laughs from bodily horror, the dark side of virus fear shows up more frequently, such as in the virulent black-oil virus of "The X-Files," the ghastly Ebola epidemic in "Outbreak," the flukelike, mind-controlling parasites from another planet in the 1998 film "The Faculty" and the microbe-caused, mutated monstrosities in the PlayStation games Extermination, Parasite Eve and Resident Evil.

On the literary front, Robert Ludlum's recent thriller "The Hades Factor" centers on a plot by a drug company CEO to create a deadly epidemic. "Mutant," a new book by Peter Clement, concerns a deadly epidemic created by terrorists, while Geraldine Brooks' "Year of Wonders: A Novel of the Plague" revisits the horrors of medieval pestilence.

Other virus-horror highlights include the worldwide plagues in Connie Willis' "Doomsday Book" and Stephen King's "The Stand" (which was adapted into a 1994 TV serial), the thinking microbes that envelop the Earth and terminate the human species in Greg Bear's "Blood Music" and the deadly combination of organic and electronic viruses that alter human evolution in Philip Kerr's "The Second Angel." A new balance of horror has emerged: We are no longer afraid of the bomb; the virus is our new boogeyman.

Inspiring this cultural anxiety are real fears: the AIDS virus, germ warfare, biological terrorism, foot-and-mouth disease, the West Nile virus and bizarre new antibiotic-resistant supergerms. Paul Ewald's recent book "Plague Time" argues convincingly that diseases once linked with genes and environmental pollution -- like cancer and heart disease -- may be attributed to pathogens. Carl Zimmer, in his 2001 book "Parasite Rex," shines a light on the body-consuming pervasiveness of parasitic invaders.

In the 1950s, our apocalyptic fears centered on radioactive fallout and global thermonuclear war. In science fiction, nuclear anxiety frequently expressed itself as nightmarish visions of gigantic insects and monstrous crustaceans terrorizing the world. After the prehistoric "Beast From 20,000 Fathoms" awoke from its million-year sleep by the underwater testing of atomic devices, the screen was overrun by reanimated-by-the-bomb behemoths and radioactive mutants -- the giant ants of "Them," the colossal lizard of "Godzilla," the enormous octopus of "It Came From Beneath the Sea," the stupendous spiders of "Tarantula" and the Cadillac-size grasshoppers that lumber down Chicago's Michigan Avenue in "The Beginning of the End."

Bomb tests, American/Soviet saber rattling, wailing air raid sirens and duck-and-cover nuclear holocaust exercises generated a paranoid atmosphere that pervaded American culture beyond sci-fi B-movies. Books, essays, television shows and prestigious films explored the medical, psychological and ethical implications of nuclear weapons.

Following the 1963 nuclear test ban treaty, atomic anxiety waned until the 1980s. A brief upsurge of nuclear jitters -- caused by the Three Mile Island accident, the Chernobyl disaster and Reagan's vast military buildup -- was reflected in movies such as "The China Syndrome," "WarGames" and "The Day After." Then the collapse of the Soviet Union significantly reduced apprehension about atomic annihilation.

During the era of bomb terror, ancient fears of disease lessened as science conquered one plague after another, including smallpox and the childhood scourge polio. Only a few movies dealt with the epidemic issue. The earliest such movie -- Elia Kazan's taut 1950 noir drama "Panic in the Streets" -- centers on a manhunt for two gangsters infected with pneumonic plague. John Sturges' 1965 suspense gem "The Satan Bug" shows the nerve-racking chase of a lunatic who has stolen flasks of a deadly virus. In both films, the epidemic threat remained unrealized.

The bloody reality of pestilence showed up in Roger Corman's "The Masque of the Red Death" (based on the Edgar Allan Poe story) and Sidney Salkow's "The Last Man on Earth" -- both released in 1964 and starring Vincent Price. Adapted from Richard Matheson's novel "I Am Legend," "Last Man" -- remade in 1971 as "Omega Man" -- follows the tormented sole survivor of a plague, who is besieged by vampiric victims thirsting for his blood.

Inspired by a post-Vietnam, post-Watergate explosion of cinematic horror and cynicism, 1970s movie epidemics elaborate the gore factor while mutating the virus into a symbol of sinister government activity. In both Robert Wise's "The Andromeda Strain" and George Romero's "The Crazies," a killer plague results from government germ warfare experiments. "The Crazies" establishes the iconography of the virus horror subgenre: plague victims writhing in agony, panic-stricken citizens flooding the streets, menacing bio-police -- in gas masks and hooded white spacesuits -- overzealously enforcing martial law, a gruesome accumulation of disease-ravaged bodies.

The king of cinematic bodily horror, director David Cronenberg, presciently turned sex into an instrument of contagion and death years before the outbreak of AIDS. In his 1975 feature film debut, "Shivers," a mad doctor engineers a sexually transmitted parasite that turns high-rise apartment dwellers into lust-driven zombies. An even more hideous parasite makes a shocking, stomach-exploding emergence in Ridley Scott's "Alien" -- a film that also recalls the monster movies of the '50s. Like "Shivers," "Alien" exploits the fear of something lethal inside our body that controls, transforms or eats us from within.

As fear of nuclear apocalypse abated, AIDS threatened another kind of apocalypse -- a biological one. As the mysterious plague spread worldwide, ghastly new microbial horrors came to light. Richard Preston's 1994 nonfiction "The Hot Zone" raised bone-chilling fears of bizarre, highly contagious new viruses like Ebola, Marburg and Lassa. Focusing on the microbe's insidious and deadly power, Preston elaborated horrific descriptions of virus-induced human body meltdowns.

Heavily influenced by "The Hot Zone" and "The Crazies," Wolfgang Peterson's 1995 movie "Outbreak" (with Dustin Hoffman) raises the level of visceral terror and paranoid hysterics -- showing human bodies exploding with Ebola while emphasizing the ease of passing the bug and the impossibility of knowing who's infected.

Following "Outbreak" and "The Hot Zone" came an epidemic of horror-of-the-virus science books, including Leslie Garrett's "The Coming Plague," Frank Ryan's "Virus X" and Richard Rhodes' "The Deadly Feasts." All raised doubts about the survival of humanity and fueled the fear of biological vulnerability. In addition, the Persian Gulf War brought us face to face with gas masks and the disturbing specter of germ warfare.

Repackaging mass fear as mass entertainment, "The X-Files" elaborates a conspiracy to spread the black oil virus and spawn a viral apocalypse. Individual episodes delve into disturbing tales of aggressive, invasive organisms such as the repulsive parasite in last season's "Roadrunner." Like other epidemic narratives, "The X-Files" condemns the very forces glorified in 1950s nuclear paranoia films: the government, the military, the FBI and their scientist and corporate co-conspirators.

Suspicion and mistrust of doctors, scientists and their pharmaceutical industry sponsors were fueled by AIDS -- by the slowness of the governmental response, the blame-the-victim defensiveness of medical professionals, the exorbitant price of AIDS medicine and the duplicity associated with the discovery of HIV. A 1993 TV biopic, "And the Band Played On," based on Randy Shilts' nonfiction book, shows medical authorities as malicious, crass, inept and arrogant.

Medical paranoia infuses the novels of Robin Cook, king of the microbe-driven thriller with "Invasion," "Contagion," "Toxic" and his most recent book, "Vector." "Outbreak" -- adapted into a TV movie called "Robin Cook's Virus" -- turned on the deliberate spread of the deadly Ebola virus by malevolent, HMO-hating doctors.

Bioterrorism adds a ghastly dimension to plague paranoia. In Cook's "Vector," neo-Nazi skinheads assault New York with weaponized anthrax. Even more terrifying, Richard Preston's novel "The Cobra Event" centers on a bioterrorism attack with a doomsday virus created in a bioreactor.

With fear of viruses on the rise, even '50s-style mutated creatures -- caused by microbes rather than radiation -- are making a comeback. In "Evolution" alien organisms mutate into enormous, buglike giants. In Dean Koontz' novel "Seize the Night" and the digital game Extermination, a retrovirus transforms people into shrieking, malicious monstrosities. Finally, in Parasite Eve -- a PlayStation game adapted from a bestselling Japanese novel -- a resurrected, prehistoric organic force causes the cells of living things to mutate into a spider-woman, a giant worm, a three-headed dog and a reanimated triceratops.

Emerging from under the shadow of the mushroom cloud, we've become enveloped in a new darkness. Uniquely fearsome, the virus goes beyond nuclear anxiety to the heart of paranoia -- provoking ancient fears of disease, dehumanization, vampirism and biblical vengeance and inciting futuristic fears of human extinction. In many ways, the virus is the ultimate horror.

Shares