As the Bush administration shifts American security and foreign-policy focus toward Asia, there is increasing evidence that the Pentagon is preparing for a new cold war, with China as the new enemy. Nowhere is this more evident than in U.S. relations with India.

The trend — which began under President Clinton — ends decades of virtual neutrality in the ongoing conflict between India and Pakistan. The new strategy relies on courting India to help contain China.

It certainly became easier for the United States to take sides after the military coup in Pakistan in 1999. India, a democracy since 1947, does seem a more natural U.S. ally than Pakistan. But India often sided with the Soviet Union in the United Nations during the Cold War, and bought Soviet-bloc weapons. And Pakistan’s long series of military rulers provided a staunch U.S. ally during the Cold War.

The U-2 spy plane of Francis Gary Powers, shot down over the Soviet Union in 1960, took off from a Pakistani airfield. When President Nixon and Henry Kissinger broke the ice and visited Mao Zedong in 1972, Pakistan paved the way. And when the United States gave $500 million a year in arms and supplies, including Stinger missiles, to help Afghan mujahideen guerrillas defeat the Russian army in the 1980s, the rebels were based in Pakistan.

But in the last decade, India opened up to foreign trade and investment, shifted away from central planning to market economics and launched a giant software industry, manned by English-speaking graduates of superb public technical universities. Some had feared that since Democrats had traditionally leaned toward India and Republicans toward Pakistan, that George W. Bush would end the India tilt. But so far, the Bush team has continued a pro-India policy. Apparently at the heart of that decision: a mutual fear of China.

India is furious that China supplied Pakistan with ring magnets and other high tech equipment to build both nuclear weapons and guided missiles. That proliferation continues to take place according to recent intelligence leaks. When Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s Hindu nationalist party took power in 1998, and quickly set off its five nuclear blasts, the Indian defense minister said it was to deter China, not Pakistan.

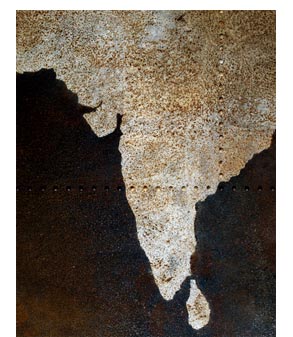

Now, according to State Department and foreign sources, U.S.-Indian military cooperation is increasing and the Bush foreign policy team is trying to find a way to lift the mandatory sanctions on India imposed over its nuclear blasts. India seeks advanced weapons and joint military training with the United States. But India remains a thorny potential ally. For half a century, it has been accustomed to being the big boy on the block, dominating its neighbors in South Asia with an often heavy hand. The United States must be sure India will not use its new American connection to further bully its neighbors. And the United States will not find India as compliant an ally as Britain or even France.

Stephen Cohen of the Brookings Institution, who is a former State Department Asia expert, says the issue of nuclear proliferation has been a major stumbling block in improving U.S.-India relations. The nuclear blasts shattered the nuclear weapons monopoly by the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council and obliged the United States to take action. A long series of discussions between then Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott and his Indian counterparts failed to push the nuclear genie back in the bottle as the Americans wanted. But it at least alerted the Americans to India’s deep-seated confidence and patience.

“In the past, India has been a less-than-great-power attempting to act like a great one,” writes Cohen in his new book “India, Emerging Power.” He believes a new generation of Indian officials is moving away from “hectoring,” which will lead to improved ties with the United States. “India is not a great power … however in a transformed international order its assets and resources become more relevant to a wide range of American interests than they have been for the past fifty years. They cannot be safely ignored in the future as they have been in the past,” he writes.

American leaders seem to agree and continue to court India. Secretary of State Colin Powell and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld attended talks July 30 in Australia that aimed at possibly merging U.S. allies Japan, South Korea and Australia into a new alliance.

Powell carefully did not say who the alliance would be aimed at — China is the only credible candidate for a threat. And Powell did not mention the other Asian power needed to complete an arc containing China’s power and protecting America’s allies — India.

A likely U.S.-China conflict, say many military planners, could begin in the South China Sea, which China claims as its territorial waters but which is also claimed in part by Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei. The United States sees the sea as international waters, through which flow most of Japan’s Middle East oil supplies. China has already clashed with Vietnam and the Philippines over the disputed Spratly Islands since 1988, and China briefly detained a U.S. aircrew and surveillance plane after it collided with a Chinese chase plane in April over the disputed sea.

India and Japan recently held blue-water naval exercises in the South China Sea and Indian Ocean, ostensibly aimed at search and rescue or combating piracy. Meanwhile Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Gen. Henry Shelton visited New Delhi recently amid talks of closer U.S.-Indian military ties. President Clinton also made the first U.S. presidential visit to India in 23 years in March 2000, winning over a normally skeptical Parliament. Clinton spent just a few insulting hours in Pakistan calling for a return to democracy.

Even if the United States is only waking up to the potential power of India, which set off nuclear weapons in 1998 and is building its own guided missiles, China has long been wary of its natural rival for dominance in Asia. The two fought a bitter border war in 1962 that China basically won, seizing large tracts of land. It continues to claim still more Indian land and until recently refused to even agree on the lines of actual control. But India is just emerging from decades — one might say centuries — of stagnation and isolation. And jut as it tries to raise its head beyond the Indian Ocean to become a world power, it is being dragged back down by its death-struggle against neighboring Pakistan.

India is expected to pass China as the most populous nation on earth around the year 2020, but remains hobbled by a guerrilla war in Kashmir sponsored by its vastly smaller neighbor — a neighbor, which Indian and U.S. analysts are quick to note, that has been able to develop atomic bombs and guided missiles through the largess of China.

Closer to home, Indian political clout has increased. More than 100 congressmen have joined what has become the second most powerful ethnic-American caucus on the Hill. “We are not so well organized as AIPAC[the America-Israel Public Affairs Committee],” said a congressional source linked to the India lobby. But when Pakistan invaded Kargil in 1999, the Indian-American lobby “flooded congressional offices” with impassioned calls for American intervention. That led to the first, clear-cut U.S. tilt in 50 years away from Pakistan and towards India.

Pakistan is also blamed for backing the radical Muslim fundamentalist Taliban movement which rose in the madrassas or religious schools of Pakistan and took over 90 percent of Afghanistan and shelters accused terrorist Osama bin Laden. So Pakistan is increasingly seen as a crossroads for terrorism, with armed militants heading to Kashmir or to Afghanistan where training camps prepare Muslim fighters from all over the world for battles in Chechnya, the Philippines, Uzbekistan, Kashmir, Algeria and even the bombing of buildings in America.

Pakistani journalists recently told me they were shocked at the negative coverage of their country in American newspapers. But after they listed their own grievances with their government — “corrupt, military run, no transparency, press is intimidated, the mullahs are gaining power, the feudals control the economy” — we agreed they were tougher on their country than the American press. Only they could not write it in their newspapers. But even if the United States has in recent years given up on Pakistan as unstable, corrupt and radicalized, before the United States can fully enlist India as an ally in Asia, a parting of the ways with Pakistan is needed.

“The tilt towards India should have happened at the end of the Cold War, but a lot of old habits on both sides prevented close accommodation and the Pakistanis were able to get U.S. policy to still treat the two countries with parity,” said James Clad, a former correspondent in New Delhi for the Far Eastern Economic Review and currently professor of Asian Studies at Georgetown University. “Pakistan was loyal in the Cold War and loyalty matters. But speaking of India and Pakistan in the same breath foreclosed opportunities. Now the disproportionate power and opportunity of India has become clear.”