Cut-rate Viagra offers, get-rich-quick schemes, loony diet plans. The strangest spam you've ever received can't compare to what's in Janet Linthicum's in box almost every day. The predatory bird researcher gets e-mail from bald eagles.

Eagles migrating from Northern California to their summer digs in North Central Canada and back send word to Linthicum about where they are and how they're doing, like sending postcards from a twice-a-year, 1,500-mile road trip.

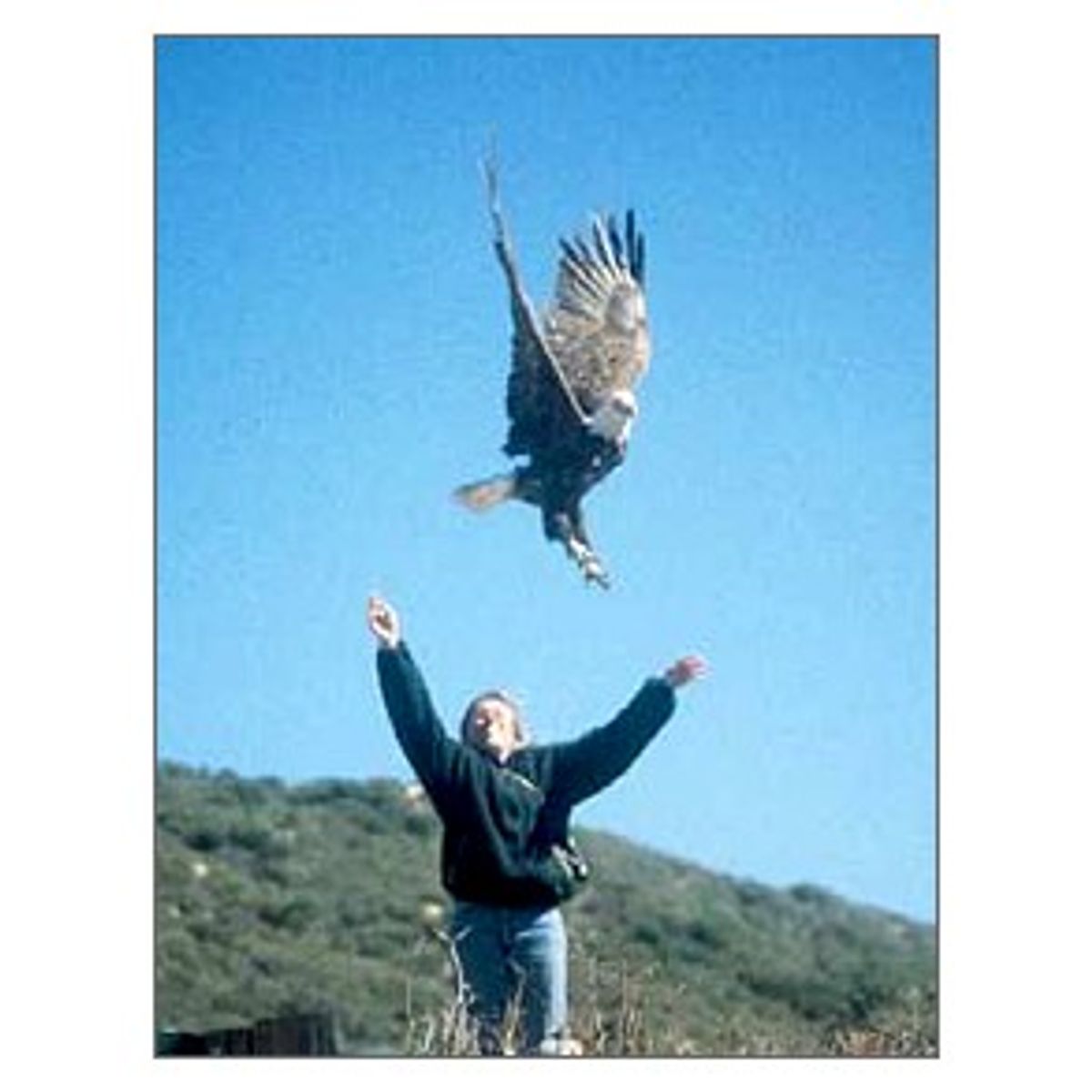

Linthicum and other staffers at the Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group have decked out the birds with special radio transmitters, which weigh less than 2 percent of the eagle's body weight. About the size of a matchbox, the transmitters are worn like a backpack with straps that go over the eagle's breast.

The radio transmitters emit a pulse -- inaudible to bird or human -- that any of the five National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration satellites orbiting the earth can pick up. The satellites are part of the Argos System, a joint environmental data collection project between France and the United States. The information collected is downloaded to ground receiving stations and then forwarded to Linthicum's in box for study.

"It's remarkable how much more information you can get with the transmitter. No matter where the bird goes you can follow," says Linthicum. In addition to learning each bird's longitude and latitude, Linthicum gets readings from an activity sensor, which determines if the bird is still alive, as well as an air-temperature sensor, which reveals if the sensor has fallen off.

Such "satellite telemetry" lets biologists learn exactly what routes the birds take on their yearly flights -- information important not just for ornithological research, but also for habitat conservation.

"People have done banding studies for years, so there was a little bit of information about bald eagle movements," Linthicum explains. "But the satellite shows exactly where they go and when they go throughout the full year. To get that kind of information, you'd probably have to band hundreds of birds."

So far, the Santa Cruz researchers have put some 15 bald eagles online -- they're currently tracking four. But at any given time there are hundreds of other birds and mammals being tracked and studied through the same satellite system by researchers around the globe. In a given month, the Argos program tracks approximately 7,500 individual objects, living and otherwise; about 20 percent of those are animals in similar studies, ranging from West Indian manatees in Florida to Malaysian elephants and porcupine caribou in the embattled Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Whales have transmitters attached to their blubber that they pull behind them as they swim. Female polar bears wear collars to monitor their movements and their proximity to other bears. Sea turtles carry dive counters in Walkman-size transmitters on the backs of their shells to see how often they take a dunk. And one study of the way nesting geese reacted to a U.S. Army helicopter training exercise involved surgically implanting heart-rate transmitters in a sample group of geese to monitor via satellite if the bird's pulses raced during the helicopter flyovers.

While humans hem and haw about the Big Brotherish implications of new tracking technologies like chip implants and global positioning satellites, it seems like the whole damn animal kingdom has already uploaded its coordinates and biological data into the matrix. Maybe we humans are just late to the party.

Started as a weather-tracking program in 1978, the Argos System provided a way to monitor surface temperature and barometric pressure in the ocean via transmitters stationed on floating buoys. But in the early '80s biologists began using the system to press the boundaries of what can be tracked and learned remotely from animals.

Biologists have long tracked animals via radio transmitters with hand-held receivers, stalking their subjects by flying over them in helicopters or following them in vehicles. But this approach obviously has its limits for birds that migrate thousands of miles, or a polar bear whose movements over ice and snow in subzero temperatures can make following along an impossible ordeal in bad weather. Ironically, satellite tracking can make the study of animal behavior into a sit-in-front-of-your-monitor experience far from fresh air and dirt.

In early studies, only large animals like polar bears could comfortably carry the heavy transmitters necessary for tracking. But as the technology got smaller and lighter and the power requirements shrank -- it can take as little as a quarter of a watt to send these messages -- Debbie Shaw, deputy director of information technology for Service Argos in Maryland, says that the biological field has exploded. Some transmitters are now as small as 15 grams, making surgical implantation a possibility.

A satellite picks up the pulse of the transmitters in about a 10-minute window. The satellites circling near the equator make it around the earth six or seven times a day, while the ones near the poles (given the shorter latitude) make their trip 14 times a day. As the satellite approaches a transmitter it picks up the signal at different frequencies depending on its proximity to the object. Using the Doppler effect, the longitude and latitude of the transmitter can be calculated with accuracy as close as 150 meters. The satellite dumps the data it receives at any of three main ground stations in Wallops Island, Va.; Gilmore Creek, Alaska and Lannion, France, where it then gets sent along to the scientists.

As for the effect on the animals, don't start cooking up dire images of nature marred by scientific hubris. Even the individual animal subjects aren't saddled with the transmitter for their entire lifespan. In the case of the bald eagles the Santa Cruz researchers track, for example, the backpacks are attached with a wax cotton embroidery thread that's designed to degrade and fall off roughly when the battery-powered transmitter runs out of juice.

Monitoring humans in the same way is mostly off-limits as far as Argos is concerned. A not-for-profit with an environmental mandate, the system is used to track humans only when they are in some kind of "loss of life" situation. "What I call crazy projects," Shaw explains. Those brave (or foolish) adventurers who embark on plans to walk to the North Pole in a month or sail around the world in a boat by themselves often have Argos with them to send an alarm and help out in an emergency rescue.

Over the years, as many mysteries of nature have been solved by the data stream from the sky (Where do spectacled eider ducks go in winter anyway?), new ones have sprung up to vex researchers. Take the puzzling case of Chessie, the West Indian manatee.

It seems Chessie took a long swim one summer from Florida up the coastal waters of the Atlantic to the Chesapeake Bay. He then explored the Long Island Sound and the East River, before cruising over to New England. Since manatees weren't known to venture farther north than Virginia, the 28-mile-a-day sea trek was cause for excitement and concern among biologists tracking the manatee via satellite.

But soon marine biologists became so worried that Chessie wouldn't make it back to Florida in time for winter that they interfered with their own experiment, captured the marine mammal and transported him back to warmer waters. "They didn't think he would make it," Shaw explains. But then the following year, the manatee with wanderlust took off again on the same trip to the Chesapeake Bay. Go figure.

The eye-opener in the Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group's bald eagle study has been that individual birds take almost exactly the same route at the same time each year. "It was completely surprising," says Linthicum. "Bird X would be on the same river in Southern Alberta at the same time."

It makes you wonder what mysteries of human behavior will be revealed when the commercial applications of technologies similar to Argos become available, as they are beginning to be. No doubt the same exhibitionists who broadcast their lives on webcams will be lining up to have their every move tracked and broadcast on the Web to their devoted fans. And just as we can now follow the individual migration pattern of a single bald eagle named Alegria or an Alaskan caribou named Blixen on the Web, how long before a GPS-enabled descendent of Jennycam starts sending out daily e-mail updates of her longitude and latitude, heart rate and body temperature? After all, isn't it time that Web performance art caught up with science, and we followed our feathered and four-legged friends out of the primordial ooze into the digital age?

Shares