"The WAY-AY-ting is the HARD-est part," squawks Tom Petty from his hit record. But he doesn't know the half of it. Aboard their twenty-eight-foot Wellcraft, Mark and Jimmy had been waiting for their dive mates to surface -- and it was getting hard indeed. Rig-dives don't usually take this long.

Thirty minutes ago Ronnie and Steve had plunged through the surface murk with their six-foot spear guns and aimed for the bottom 400 feet below. Not that they'd reach it -- voluntarily or alive, anyway. They'd probably turn around at 230 feet or so if nothing big showed up. Why push it?

Some would say they were already pushing it. Dive manuals say the nitrogen (80 percent of what you're breathing) buzz starts at 100 feet. "Rapture of the deep" Cousteau called it fifty years ago. "Deep-sea intoxication" according to his contemporary, Hans Haas. "Death catches the diver in a butterfly net whose mesh is so soft it closes in on him unnoticed ... one loses all misgivings and inhibitions and then, suddenly, comes the end."

"Martini's Law" we call it nowadays -- every fifty feet of depth equals the effects of one dry martini on the human brain. Bad enough by itself, but they also say that the oxygen (the remaining twenty percent of what's in the tank) becomes toxic to the human central nervous system at 218 feet -- blackouts, hysteria, derangement, convulsions, seizures. Grim things if you're in your living room; much grimmer 200 feet under the Gulf. These authorities advise recreational divers to haul back at 130 feet.

Ronnie and Steve were on a hunt, a hunt where you close to within feet of the prey before slapping the trigger. So if something big did show up down deep during the dive -- and Ronnie or Steve stuck him ... and the fish got a couple of loops of spear gun cable around them ... well, that's what I meant by voluntarily and alive.

Swells get big out here, and each one jerked the boat violently against its mooring. The boat was twenty miles off the Louisiana coast tethered by a rope and "rig hook" to an oil production platform. This steel monstrosity had a deck towering a hundred feet above them and a three-acre maze of legs and crossbeams that plunged four hundred feet to the Gulf's floor. Below that, pipes poke down for two miles and suck out the oil like huge straws. The whole thing gives "eco" types the willies. But Mother Nature -- that bumbler -- has yet to design a reef even half as prolific.

Ronnie and Steve were both thirty-one years old. They'd been diving together for years, as a team. They'd both go down with guns but whoever shot first would expect the other to come lend a hand during the ensuing melee. Jimmy and Mark had a similar set-up. All on the trip that morning were experienced rig divers in peak physical condition. Ronnie himself was a dive instructor.

So his dive mates suspected trouble. Something had to be wrong. Steve and Ronnie should have surfaced ten minutes ago.

This "rig-hopping" or "bounce-diving," as we call it, doesn't take long. You hunt your way down through the steel labyrinth as massive schools of spadefish, bluefish, and assorted jacks part grudgingly to make way. Covered with barnacles, sponges, coral, and anemones, this metal maze seems a world apart from the unsightly structure above. You forget they're connected. Fish surround you the entire dive. But you ignore them. You're after the huge ones -- the one-to-three-hundred-pound monstrosities that lumber through the murky gloom that forms on the muddy floor of the Gulf. You're not a voyeur down here either; you're a full-fledged participant in nature's relentless cycle of fang and claw. If you find a big fish, you stalk him and spear him. Then the fun really starts -- depending, of course, on the size of the fish and the accuracy of the shot.

If the six-foot shaft doesn't kill or paralyze the fish by hitting the spine or cranium, you've got to get to him somehow, then straddle and paralyze him. Rodeo cowboys make good rig divers. You stick your arms through the spear gun bands, run it up on your shoulder and start yanking him in, as you fin towards him. Then you either reach in with a gloved hand and start ripping out his gills or grab your ice-pick and go to work on his head.

We used to employ dive knives for the coup de grace. But that takes too long and involves too much effort. Any economizing on bottom time and exertion figures big when you're 200 feet under the Gulf, immersed in the murk and buffeted by a three-knot current. And, oh, there's that two-hundred-pound fish on the end of your spear gun -- the brute dragging you around and battering you against the beams, and he shows no signs of fatigue.

Done right, the ice-pick plunges into the cranium on the first or second jab. You twist it around and jab again, then again and hopefully the beast stops lunging and starts quivering. Now it's time to start up -- but not too fast. Remember, you're at two hundred fifty feet now.

But not too slow either. You've only got five hundred pounds of air left. And it's getting damned hard to suck it out this deep. It'll get easier on the way up. So if you can't straddle and paralyze the fish, there's no choice but to eventually let go of the gun -- unless you're not thinking clearly because the fish went on a rampage through the rig and bounced you into the barnacled beams like a human pinball (back in the '50s the guys wore football helmets for this type of rollicking fun). But even without a rig-pummeling, your brain's hopelessly fogged -- "narked out" as we say. There's no escaping nitrogen narcosis at this depth.

So if nothing big -- big enough, I should say -- showed up down there, Ronnie and Steve should have ascended. Five minutes on the way down, three minutes looking around, another five minutes coming up. Nothing to it. There's not much bottom time at these depths, five minutes tops; therefore: Steve and Ronnie should have surfaced ten minutes ago.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

These "rigs," as locals call the offshore oil platforms that dot the Gulf off Louisiana's coast, claim several divers each year -- not the rig itself, of course, but the waters under them. And these particular ones always claimed a disproportionate share, three divers in the summer of '99 alone.

Not all accidents occur in the depths. A few years back a diver watched his buddy stick a smallish (thirty pound) cobia at some rigs a few miles west of here. Cobia favor the top portion of the water column in the summer. The diver speared this one at around 30-foot depths -- nothing to it. "A breeze," figured his buddies as they watched him tussling with the fish. They were running low on air and saw that the fish seemed under control, so they gave the "O.K." signal, saw it returned, and made for the surface. They clambered aboard the boat where another buddy was waiting and fishing.

Twenty minutes later, their buddy hadn't surfaced. Worse, no bubbles seemed to be rising from the depths. They both suited back up, plunged in and quickly spotted him, casually sitting on a beam no more than thirty feet down, the fish still darting around him. What the ... ? No bubbles rose from his regulator and he seemed to be in an awkward position, ensnared in spear gun cable.

They swam over, and while one struggled with the flesh-shot fish the other began the grim task of unraveling the steel cable from around the diver's neck, where it had crushed his trachea and strangled him as efficiently as the garrote of medieval torture chambers. And that was a small fish. Even a thirty-pound fish can pull a diver around.

It's best not to dwell on these things. "Stay calm" is the cardinal rule of diving -- rig-diving especially. But when your buddies have been down thirty minutes and no bubbles seem to be ascending through the murky water ... aha -- there's some! But that could be anything -- some pipe on the rig breaking wind, some air pocket let loose by one of these monstrous swells.

The water's deep out here. The current's vicious, and the murk layer (silty freshwater floating over the heavier saltwater) is always around. Sometimes it's thin, often thick, and occasionally impenetrable, depending on river levels. The visibility can range from the hundred feet of Belize to the ten inches of Mississippi river on the same dive. But the fish are plentiful and huge. Most of Louisiana's spear fishing records (which are also the nation's) are wrestled to the surface and winched aboard around these rigs.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Still no bubbles seemed to be rising and Jimmy watched as a glum Mark, the only one with bottom time left, started suiting back up for another 200-foot plunge, this time without his gun. There was nothing on Mark's face to reflect the giddy thrill in his gut that accompanied his first dive an hour ago. He'd be hunting again, but for his buddies this time, afraid of what he'd find. They'd been too deep too long.

Then Steve suddenly popped to the surface, unadvertised by any bubbles, just as Mark was buckling his weight belt.

"Steve!" Jimmy yelled as he leaned on the gunwhale, then, turning to Mark, "There he is!" They were jubilant -- until they noticed that Steve wasn't moving. He was bobbing in the swells face down.

Steve was unconscious. He'd been unconscious for several seconds -- very crucial seconds as it turned out -- the seconds when he was ascending the last hundred feet to the surface. Because of the change in pressure, the volume of gas in a scuba diver's lungs quadruples from 90 feet to the surface. Something has to give. When a diver exhales, the extra air is released through the windpipe. If he's holding his breath, what gives is lung tissue, which ruptures, or releases bubbles into the blood. The danger of an arterial gas embolism -- a bubble forced out of the lung tissue by the decreasing pressure -- is greatest here. The bubble travels through the arteries till it lodges in the heart, triggering a heart attack, or in the brain, triggering a fatal stroke.

Steve was still unconscious when they hauled him aboard, but he came to quickly and started coughing up blood. Not a good sign. "Ronnie's still down there," he gasped. "He's tangled with a huge grouper. I couldn't help him ... . I ran out of air."

Mark plunged in and descended 200 feet, his gut in an icy knot, his brain partly numb, partly aflame with ghastly visions. He reached the murk, but found nothing. No Ronnie. No huge grouper. He ascended a bit and started circling the rig, looking for bubbles -- praying, pleading, straining to detect that tell-tale little line of silver globules that meant his friend was still breathing somewhere down there. But there was nothing but a murky void below him, with fish finning lazily around. How can they be so damn calm? Mark thought to himself, when I'm sucking air like a maniac and my goggles are filling with tears! Don't they realize what's going on? It seemed strange. Everything seemed strange at that point. Finally his own air ran low and he finned up.

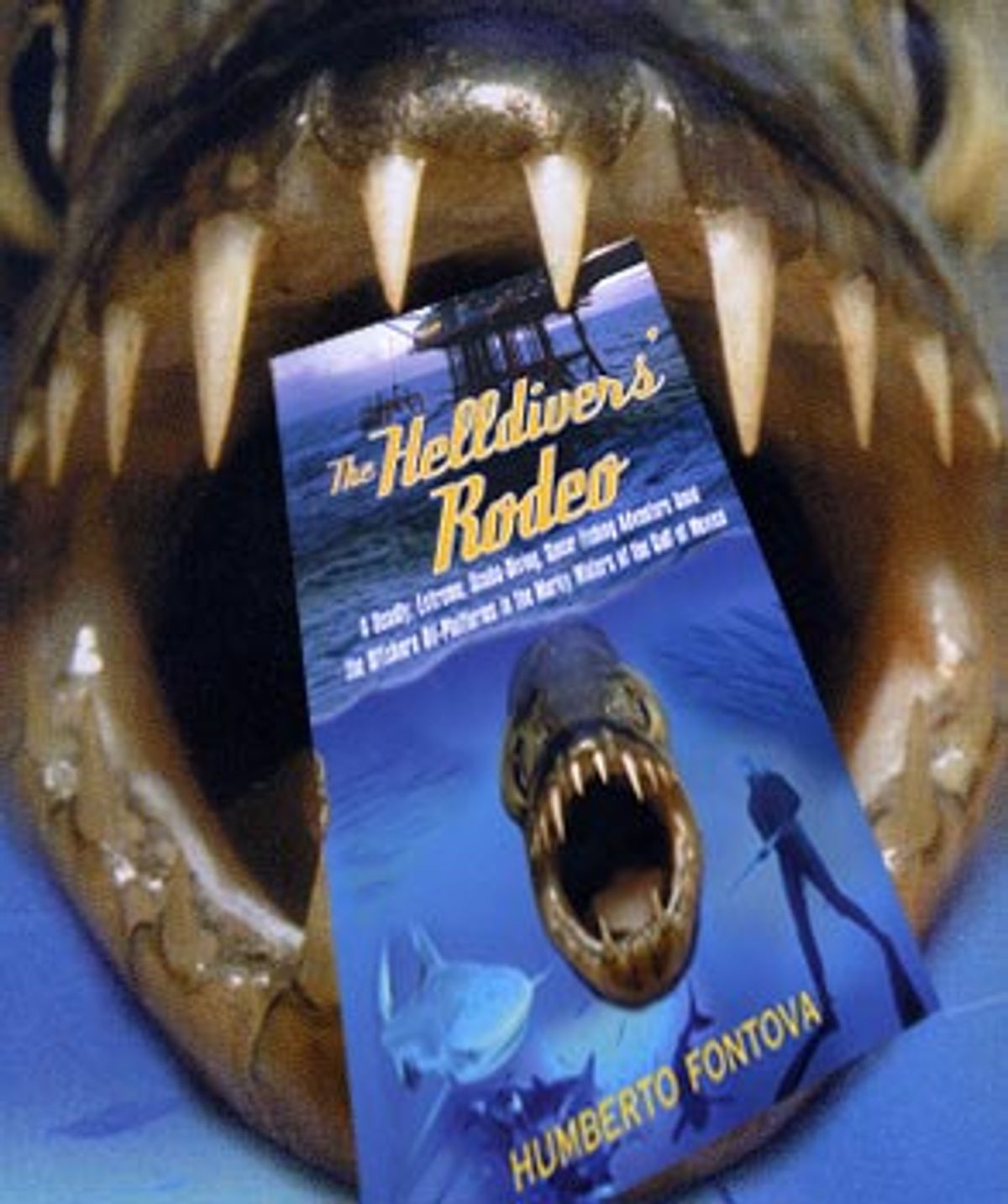

The next day the New Orleans Times Picayune ran the headline: Scuba diver spears 300-pound fish, disappears.

Oddly, Steve's passing out is credited by some with saving him. This opened his glottis and allowed air to escape from his expanding lungs as he ascended, preventing a pulmonary barotrauma, or a ruptured lung -- preventing a fatal one anyway. He coughed up blood for weeks.

He'd seen Ronnie spear the 300-pound fish below him and headed down to help. The shaft had missed the big grouper's spine and brain, so the fish was going crazy. It already had the cable wrapped around Ronnie a couple of times. Steve plunged into the melee, grabbing cable, spear, fish, whatever, and got himself wrapped in the process. In the madness and confusion the regulator was somehow yanked from his mouth. He was reaching frantically for it when another hard yank from the fish actually cut his regulator hose and bubbles started spewing everywhere. Now he's 200 feet underwater, wrapped in the cable, with no air. He fumbled for the hose thinking to stick it in his mouth but soon it expired. Somehow he untangled himself and started up. Somewhere on the way up -- his dive mates estimate about halfway -- he blacked out from lack of oxygen. That's all he remembers until he was in the boat.

He recovered completely and moved to Belize for a year ... had to get away.

Shares