Who, you may be asking yourself, is ELLEgirl? Well, she carries her cellphone in a tiny stuffed animal frog; graffitis her own handbags rather than shelling out for Stephen Sprouse-scrawled Louis Vuitton luggage; wears magenta eyeliner and pink fishnets; bleaches her teeth once a week; considers Chloë Sevigny a fashion icon; knows that Sisqo's favorite food is fried chicken; and buys $238 Marc Jacobs strapless dresses.

In other words, if Elle magazine is the 55-year-old matriarch of the high-end fashion glossies, the teen spinoff ELLEgirl -- hitting the stands this month -- is her sassy, somewhat spoiled but ultimately youthful daughter.

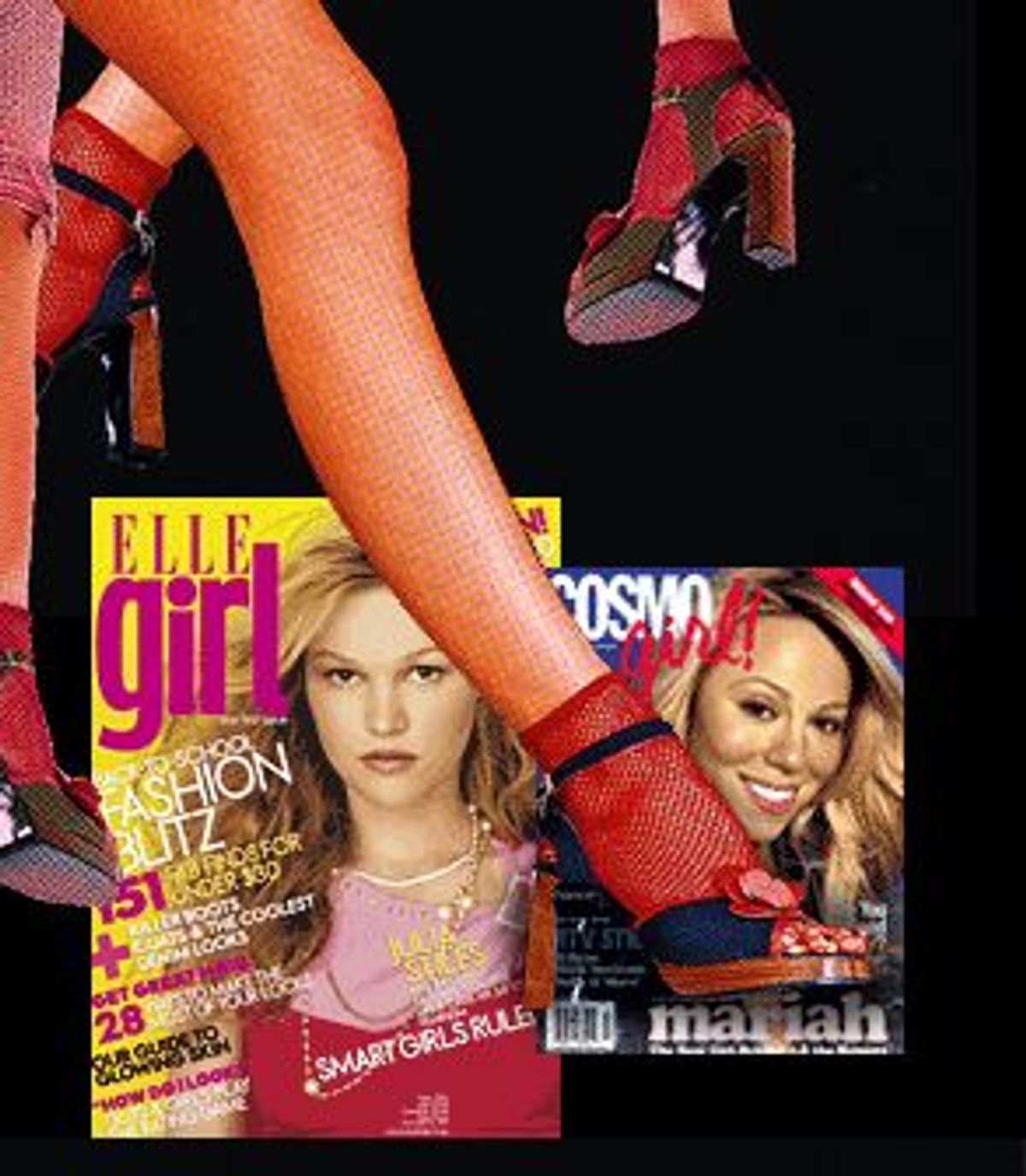

There just might be a few thousand teenage girls across the country who fit this exact description (up and coming teenage starlets; precocious daughters of hotel magnates and a few creative and ambitious high schoolers). They now have a magazine to fit their lifestyle. For the rest of teenage America, editor in chief Brandon Holley assures us in the welcome letter of the magazine's first issue, aspiring ELLEgirls can just emulate the personality of actress Julia Stiles, "the ultimate ELLEgirl": "She's confident, attractive, independent and scary smart."

The teen magazine market has undergone a small revolution in the last three years, as magazines for grown-ups have given birth to spinoffs for their nascent teen audiences. People magazine was the first to realize that a huge, pop-culture-crazed high school market was primed for magazines that were a tad more adult than Tiger Beat, but still tailored for their tastes. Teen People merely regurgitated People's formula of celebrity fluff and feel-good profiles of "real people" for the teenage market (i.e., Britney instead of Whitney, Julia Stiles instead of Julia Roberts), and the plan worked: A million teenagers now read the magazine every month.

The second to market was Cosmopolitan's CosmoGIRL! (Which is not to be confused with the similarly named ELLEgirl: Note that CosmoGIRL!, in true Helen Gurley Brown style, capitalizes the GIRL suffix and includes an affirming exclamation point for emphasis, while ELLEgirl demurely focuses on the more elitist French prefix.) CosmoGIRL!, now a million readers strong, was followed by Teen Vogue, a quarterly that currently boasts about 500,000 readers. ELLEgirl, meanwhile, is fashionably late to the party. As yet, we have not been graced with Harper's Junior Bazaar, Lil' Miss O or Girls In Style; but just you wait. (Full disclosure: Two years ago, I wrote Web site reviews for CosmoGIRL!)

By virtue of their ancestry, these new magazines are an odd and somewhat confused lot, especially fashion bible spinoffs like ELLEgirl and Teen Vogue, whose traditional brand images are unaffordable and unattainable chic, but whose teen versions also address the age and interests of their market -- boys 'n' Britney 'n' girl power! They are a breeding ground for little Lolitas, a mishmash of adult imagery and naively youthful concerns, part celeb fanzine and part sophisticated fashion education. They proffer inspirational stories, training courses in self-confidence and even a smidgen of feminism (or, as the ELLEgirl hedges around that dread term on the cover, "Dare we say it? Feminism") -- all packaged alongside gossip, makeup hints and spreads featuring $520 rabbit fur bomber jackets.

In a sense, the new teen mags are tween magazines. They are an amalgamation of the mixed-up, hi-lo messages transmitted to the modern teenager on a daily basis: Be an adult but remain a kid; look sexy but stay a virgin; dress like this model but maintain your own personal style.

The life of a teenager is all about trying to filter these mixed messages under the influence of hard hormones. The mission is to define the line between individual expression and media-defined conformity. Am I wearing low-cut hipster jeans because they express my self-image, or because I was bombarded with Old Navy ads and fashion magazine editorials that suggested that I should buy low-cut hipster jeans?

This dilemma is not unfamiliar to most consumers, but when it comes to the palpable angst of teenagers, glossy magazines are handling flammable goods. Unofficially, these publications are charged with the added responsibility of teaching positive messages. Can they? Should they? What if they say they will and merely pretend?

"It is tough, and you can't underscore enough the responsibility of a teen magazine editor," Holley agrees. "These girls are really important, and it's a big responsibility to live up to their expectations."

Of the new spinoff magazines. CosmoGIRL! is the most Tiger Beat of the bunch -- offering such girly goodies as Britney Spears stickers and cut-out posters of hunky teenage babes with their shirts off; but it's also the most blatantly feminist -- or, in the fuzzy colloquial lingo of the teen mags -- "girl power"-inspired. "CosmoGIRL! is a place where we're all strong," chirps the August letter from editor in chief Atoosa Rubenstein, whose early internship at Sassy magazine is evident in her ideology. "We wanted to create a world. The kind of world we wanted to live in but couldn't seem to find. You know what I mean, right? The real version of our daydream. A place where we're all accepted. All beautiful. All nice to each other. All friends. Strong, full of guts and passion. That's what being a CosmoGIRL! would mean."

ELLEgirl and Teen Vogue aren't nearly as gushy; rather, they cop the slightly glacial attitudes of their parent magazines. While CosmoGIRL! serves up advice for the lovelorn, celebrity gossip and most embarrassing moments galore, ELLEgirl and Teen Vogue offer a stricter diet of high fashion and makeup.

That's not to say that ELLEgirl isn't also about girl power; but this magazine's version of the mantra has less to do with being strong and a lot to do with shopping wisely. "So what is ELLEgirl about? Helping you discover your personal style, starting with your closet," explains editor Holley. "If you try something new, you might discover something new about yourself. Yeah, it's just clothing and makeup, but that's only the beginning. Once you start experimenting and taking chances, there's no telling where you'll end up."

There are moments when this ideology translates nicely: especially when the magazines track down "real girls" in the streets of London, New York, Tokyo and Los Angeles and ask them about their looks. Unfortunately, "personal style" also manifests itself as the same old strict beauty regimens teens have been spoon-fed by magazines for decades.

While ELLEgirl's "personal style" frowns on anorexic ballerinas -- according to a feature article in the magazine -- it also, apparently, condones a beauty routine of self-bronzer applied twice a week, weekly hot oil treatments and daily manicures, plus regular tooth bleaching and skin masks.

Then there's Teen Vogue, which gushes that "finding yourself and what makes you feel happy and healthy [is] always in fashion," but also runs ads for breast enhancement tablets. For $229.95, you too can grow bigger boobs, "feel more beautiful and sexier than ever" and have "more self esteem, more confidence." Sure, it's advertising, and maybe today's savvy girls are able to discern between editorial and ads (though, considering how often the two are conflated in the world of fashion magazines, that may be an unfair assumption); still, the messages between those covers are decidedly mixed. What's next, advertisements for preventive cosmetic surgery and liposuction, all in the name of personal fulfillment? (When the New York Times interviewed Teen Vogue editor Amy Astley about the ads, she responded that "I am personally committed to having Teen Vogue promote images of health and well-being for our readers.")

More disturbing, however, is that some of the fashion-bible spinoffs are upping the ante in their teen glossy fare. Take, for example, the predominant presence of pricey designer Marc Jacobs, whose clothes are featured in more than a dozen fashion spreads across ELLEgirl and Teen Vogue; his outfits, while preppy and perhaps appropriate-looking for teenagers, also hover in a price range of $200 and up. Fashion spreads in these two magazines, while often avoiding the dread midriff and leaning toward pocketbook-friendly labels like Old Navy and H&M, also include a liberal sprinkling of catwalk designers like Vivienne Tam, Miu Miu, Anna Sui, Katayone Adeli and Alberta Ferreti.

Should we expect any less from magazines that are, ultimately, about peddling products? The answer from teen mag editors tends to be a bit murky, evasive or just plain indignant. Teen Vogue editor Amy Astley says that such high-end spreads are meant to supply "inspiration" for fashion rebels. "Fashion now is about scrapping the 'rules' and suiting yourself. You can really see and feel this spirit of independence in our fashion stories this month." But it feels an awful lot like consumption training for little girls: You too can aspire to own the $320 Chloe jeans that even your mother can't afford.

"I don't think that to be into fashion and into your style means that you have to be a label whore," Holley explains. "This book [ELLEgirl] is totally not about creating a fashion victim mentality. This magazine is giving a girl a chance to dress the way she wants, think the way she wants, not be a lemming. It may sound shallow, but there's nothing wrong with being strong and looking good. "

But suggesting that empowerment can be found in great black pants seems more of an encouragement for conspicuous consumption than personal fulfillment. Consider the bubblegum wisdom of actress Tara Reid, who, when interviewed about life's little dilemmas for Teen Vogue, explained, "I can handle a full plate because the alternative to being busy is being bored and broke, but being without great black pants makes me depressed."

CosmoGIRL! may want to create a place where we're all beautiful and strong; but it also makes a magazine chock-full of advice on how to "look like Gwen Stefani" and "five ways to look thinner without dieting," not to mention hair-removal ads and pimple cream and makeup tips galore. CosmoGIRL!'s Rubenstein asserts that this is done in the name of feminism, though:

"The essence of our mag is about giving girls power and empowering them when it comes to their lives," she says. "Even makeup -- it may seem the antithesis, but the fact is girls are into makeup. Instead of throwing products at them and saying buy buy buy, we are saying, 'Here is how you put [different looks] on.'"

So is this a case of self-esteem finding handy expression in cosmetics or magazine editors rationalizing the fact that their magazines use adolescent insecurity to hawk eye shadow and thigh cream? Fashion and feminism are not necessarily diametrically opposed, but the agendas of magazine editors and advertising departments often do run at odds with each other.

Let's look at the numbers: The teen market packs a lucrative wallop of $158 billion in spending power, 75 percent of which female teens spend on clothing. This market is larger than it has been since baby boomers were teeny-boppers -- there are now 31 million teenagers in America alone. Not surprisingly, even as the rest of the economy has slumped, CosmoGIRL! has seen an increase in advertising over last year.

All in the name, it seems, of empowerment:

"Of course we write about products -- our girls are shoppers," explains Rubenstein. "But the biggest section of the book is Inner Girl -- which is about self-esteem. While we certainly have beauty and fashion pages, they are part of an editorial mix that is very focused on empowering the reader. And that's our mission -- not to make her feel like she's been bombarded with product that doesn't make sense to her."

This same conundrum seems to exist in the magazines' treatment of sex, or studious nontreatment of it. ELLEgirl is almost completely devoid of boys; Teen Vogue offers marginal gushing plus an article warning against mimicking oversexed starlets. Teen People, as a gender-neutral magazine, offers "Hot Guys in Music" features but generally offers little dating advice and certainly no sex. CosmoGIRL!, on the other hand, is heavy into boys, but in a squeaky clean and sex-free kind of way. While Cosmopolitan's August cover offers "Our Most Outrageous Lust Lessons," CosmoGIRL!'s cover promises wholesome, sex-free romance instead -- "Find Your True Love" and a feature on Reese Witherspoon billed as being about "What it's like to be loved by Ryan [Philippe]" (Not, alas, about what it's like to be the industry's most successful young comedic actress.)

But the disconnect between ads and feature copy is blatant. Articles like "How to Slow Him Down" and "Make Your Summer Love Last" are wedged in next to a Guess advertisement that features a woman frolicking in a jean jacket, floral bikini underwear, shredded leopard knee socks and acid-washed cowboy boots; or an ad for Levi's Superlow jeans, which features a woman pressing her crotch against a boy's face. In Teen Vogue, there's a strange, winking ad for Diesel, featuring two white-faced mannequins and the satirical message "Save yourself: don't have sex. We are 110-year old virgins and proud of it. By keeping our juices to ourselves, we've prevented aging." And in ELLEgirl: Calvin Klein ads featuring teenage kids hanging out in their underwear and pouting insouciantly.

Holley feels no need to apologize: "This demographic is bombarded by sex images ... they are comfortable with that." But if the point of these magazines is to be 100 percent budget-friendly, sexually appropriate and pop-culture relevant -- while, all the while, preparing their readership to upgrade to the "adult" version of these magazines once they turn 17 -- they aren't necessarily succeeding on all counts. This mix of girly-girl youthfulness -- Bonne Bell lip gloss, 'N Sync profiles and teddy bear backpacks -- and grown-up sexual images, arch references to Fifth Avenue living and sophisticated adult-appropriate fashion often just feels schizophrenic.

Then again, adolescence is schizophrenic. There is a strong argument, frequently made by teen mag editors, that they are simply giving their readers what they crave. Today's precocious, media-savvy teens know their Prada and their belly chains and the wonders of the G-string from a cornucopia of pop culture media sources: Why pretend that a slightly whitewashed version of adult magazines should somehow shield them from this reality? The popularity of the magazines hints that kids felt that there were no magazines out there that spoke to them; perhaps the message being sent by these new adult mags for teens is that our kids are more grown up than we allow ourselves to believe.

As a feminist, it's easy to bemoan the scarcity of teen mags that are edgy, frank and very liberal. Where are the youthful versions of magazines like Bitch, Bust, GURL or (formerly) Sassy? But those publications, of course, are able to be less product-centric and more focused on pure self-empowerment because they aren't mainstream. They have given up a claim on the lion's share of ad revenues, sometimes frightening off advertisers with frankness, and have paid a price for their rebellion.

What not have it all, then? Co-opt the positive messages of the girl-zine world and mix them with the cynical messages of corporate America. Give some column inches to Girl Power and sell, sell, sell. Pop star eyebrows, hair mascara, jean jackets, Chanel perfume -- all can be sold in the name of self-improvement, self-esteem and the pursuit of true love 4ever.

And teenagers are buying. As Holley sighs, "You want to do the feel-good mag? Great. But [teens] want to read about this stuff too. What's wrong with giving them that?"

Shares