It may sound like damnation with faint praise to say that "Hardball" isn't nearly as bad as it could have been. Lord knows the movie, about a Little League team from Chicago's Cabrini Green housing project, contains more than its share of schmaltz: slow-motion sequences, sappy music -- and not to mention a scene in which a group of inner-city kids, attending their first Major League ballgame, beam and cheer when Sammy Sosa waves to them from the field.

But even if "Hardball" is mostly soapy formula at its core, it's a formula that at least finds a satisfying groove. In places, the movie is funny and fun. (Reportedly, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley was dismayed by the "bad" language used by the kids in the movie. It now has a PG-13 rating, and contains plenty of language that many parents are likely to find objectionable, but personally, I wouldn't hesitate to take a reasonably mature 9-year-old to see it. I'm not sure the language is worse than anything the average school kid hears on the playground.)

And although "Hardball" starts out shakily, particularly in the way it overdramatizes the roughness of Keanu Reeves' character, director Brian Robbins finds better footing as the picture moves along. "Hardball" may be sentimental at times, but it doesn't soak in its own syrup.

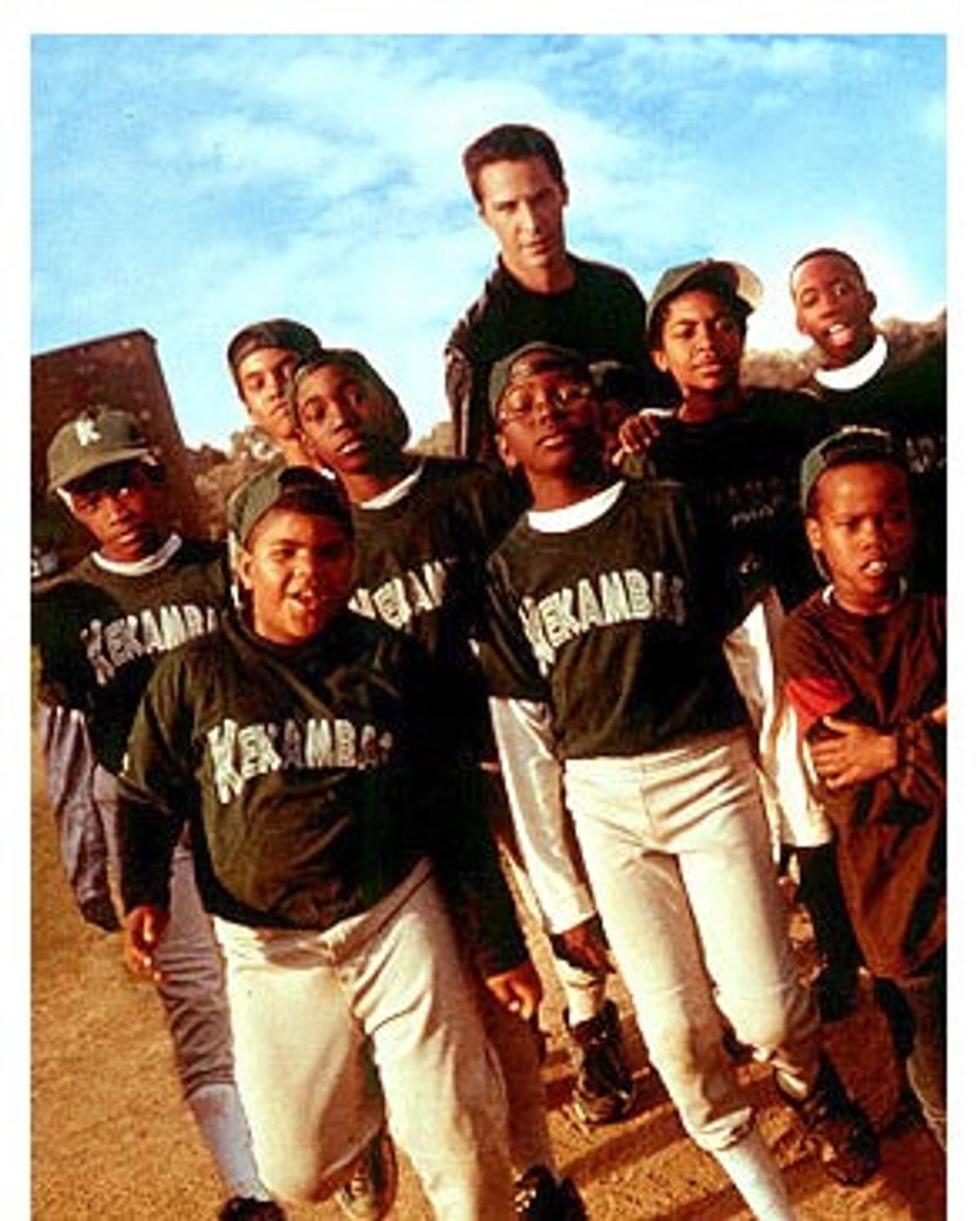

Reeves plays Conor O'Neil, a lowlife gambler and ticket scalper who finds his life changed when he starts coaching that Little League team. O'Neil is beset by thugs as the result of his mounting gambling debts and turns to a solvent buddy (Mike McGlone) for help. His friend agrees to give him the money he needs, but only if he'll help coach an inner-city Little League team. The buddy bails out -- the program is part of his corporation's community outreach program, and he's happy to ditch his coaching duties altogether. Conor suddenly finds himself on his own, trying to keep the team active in the league for his own selfish purposes.

Naturally, he finds himself won over by the kids' candor and, of course, their feisty inner-city spirit. But neither Reeves nor the actors who play the kids succumb to the excesses that you'd think a story setup like that would invite. Reeves doesn't bond with the kids in a goopy way: At first he's just offhandedly amused by them -- he uses that deadpan "Who, me?" demeanor to great effect, looking at them as if he can hardly believe what funny little men they are. They knock him out with both their silliness and their resilience. If his character ends up a redeemed man, the way Reeves plays him, he's a man redeemed mostly by good company: He simply likes hanging out with these kids, and he comes to realize that the company you keep says a lot about who you are.

Diane Lane, as the kids' teacher and Conor's love interest, has little to do, but her sense of restraint and subtlety helps keep the movie on course. And the kids themselves are a kick to watch: DeWayne Warren's G-Baby is a howl -- he's one of those little guys who has a prematurely little-old-man forehead, wrinkled and expressive, and his line delivery has a matching "old guy in a kid's body" swagger. Then there's the sight of team pitcher Miles (Alan Ellis Jr.) stepping up to the mound with his headphones on: He's addicted to Notorious B.I.G.'s "Big Poppa," and you can see how the sound of it seeps into every bone and muscle of his body just before his windup.

Robbins doesn't milk the inner-city setting dry: When he shows the kids returning to their homes at supper time, terrified of walking the gantlet of bigger, older thugs who block the way to their apartment complexes, it seems believable, not overdramatized. (The movie is loosely based on a book by Daniel Coyle about Cabrini Green Little League teams in the early '90s, but it also jibes with some of the scenes described in Alex Kotlowitz's astonishing 1992 book on the projects, "There Are No Children Here.")

There's melodrama and tragedy in "Hardball," and the movie threatens to careen off base several times. But it always manages to right itself, if a little awkwardly. "Hardball" isn't the most original picture to come down the pike, but it has enough spark in it to keep it from wallowing in its own good intentions. It may follow a formula, but sometimes formula equals comforting routine. And there are times, in the movies and elsewhere, when routine is exactly what you need.

Shares