You might be in the mood for diversion right around now, and the ultra-low-budget office comedy "Haiku Tunnel," for all its limitations, has a mysterious power I found almost comforting. Actually, the charm and the shoddiness of "Haiku Tunnel" stem from the same source. It's basically a San Francisco underground theater production that somehow escaped onto the movie screen without losing any of its eccentric, insular qualities.

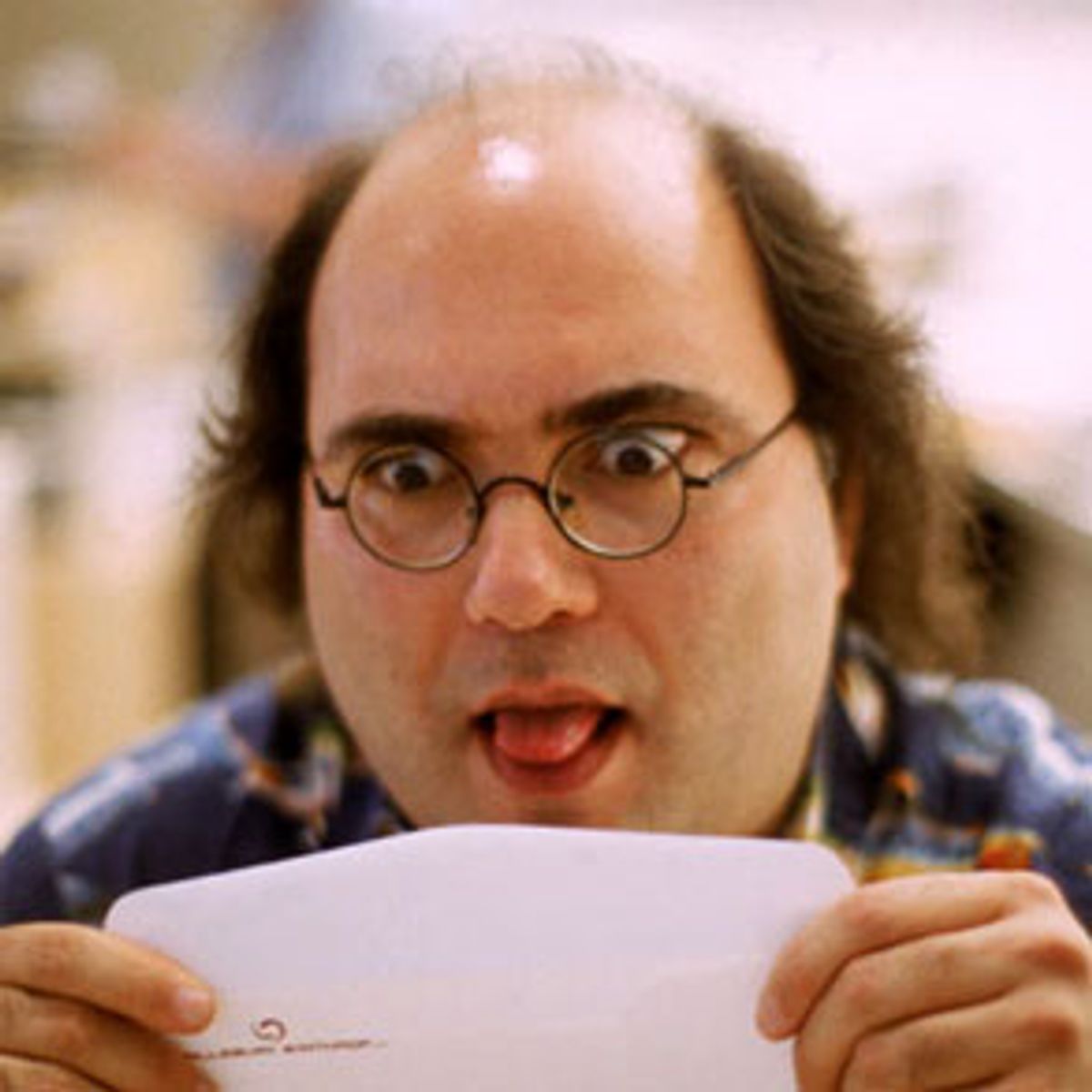

I doubt that Josh Kornbluth, the co-writer, co-director and star of "Haiku Tunnel," is destined for a Hollywood career; his appearance, which simultaneously suggests Woody Allen, Jacques Tati and the Buddha, is just too peculiar. But he's a distinctive comic talent, the kind who either irritates you beyond all measure or makes you giggle uncontrollably (or, not infrequently, both at once). "Haiku Tunnel" may appear to be a fable about an aspiring novelist who is almost monastically devoted to his temp-worker status, but that's really just an excuse for showcasing Kornbluth's stammering, mugging, endlessly self-aware persona.

Kornbluth can be a captivating performer but he isn't much of an actor; he's much funnier trying to talk to a computer printer in its own language, or lost in reveries about his bed, than he is relating to other people. When the film ventures into the world outside the reverberating "haiku tunnel" of Kornbluth's own ego, its weaknesses become painfully obvious. Like Allen at his best, however, Kornbluth is capable of convincing you that his intense self-consciousness is a world sufficient unto itself.

Kornbluth has been a longtime temp worker in real life, although he assures us, leaping from one foot to the other in a nervous prologue, that the temp named Josh who winds up at the law firm of Schuyler & Mitchell (check those initials) is not really him. Josh goes to work as secretary to an infamously picayune tax attorney named Bob (Warren Keith), who stands around his office asking speakerphone questions like, "Can we depreciate the hole as it fills up over the years?"

Josh's immediate supervisor is the head secretary, Marlina (Helen Shumaker), a half-sinister, half-seductive figure who seems like a distant cousin of Cruella DeVille. As he expects, the other employees all regard him as little more than a breathing article of furniture, at least until Marlina presents him with the ultimate Faustian bargain this world has to offer: "Do you want to go perm?" Purring with an allure that is more than sexual, she adds, "The firm will cover your psychotherapy!"

This is a serious existential crisis for a man who lives in a decrepit converted garage (which in San Francisco probably costs $1,500 a month) and whose entire life seems dedicated to transience and instability. "My one constant," Josh reflects, "was to find the escape hatch whenever perm-ness called."

But whatever gestures Kornbluth makes toward a study of a guy who can't commit to anything -- a girlfriend, a job, an apartment, a novel -- are mainly in passing. The film's real focus is on Josh's moonlike face, expanding with infantile wonder as he considers the marvels of office life. When Marlina shows him to his "room" on his first day at S&M, he muses, "It looked like a desk in a hallway. But she had called it my room. It must be a room."

When Josh goes perm, he is instantly befriended by his co-workers, especially perky Mindy (Amy Resnick), laconic Clifford (Brian Thorstenson) and no-nonsense DaVonne (June Lomena). Unhappily, these skilled stage actors don't seem aware that they need to modulate their camped-up performances for the screen, and the script by Kornbluth, his brother Jacob and John Bellucci only offers canned, TV-style characterizations.

"Haiku Tunnel" doesn't quite have a plot, but it clings to a central thread involving 17 of Bob's letters that "have to go out right away," as he self-importantly informs Josh. Anyone with experience in office life knows how mundane tasks like this can assume an almost mythical significance; the letters loom larger and larger as they get later and later, languishing in Josh's out box, becoming accidentally coated with glue and candy and even leading him into an ill-fated romance.

Lawyer Bob is supposed to be satanic but comes off only as a corporate buffoon, while Marlina, who is clearly meant to be a key figure, never comes into clear focus at all. Is she a Circean witch? A noble soul beneath a frigid exterior? A succubus carrying a hidden torch for Josh? (Who has an improbable tendency, it must be said, for attracting babealicious women.) All of these interpretations are possible, but the movie doesn't spend enough time developing its non-Josh characters to make any of them into real people.

Still, for all this caviling, the near-fatal cheapness of the sets and the rudimentary nature of the Kornbluth brothers' direction, "Haiku Tunnel" captures something inexpressible about the clannish nature of corporate-proletarian existence. The Haiku Tunnel itself, an engineering project in Hawaii whose specifications Josh is assigned to type, becomes a metaphor for the cavern of temp-worker life. Anyone familiar with San Francisco's cultural fringes will delighted in the cameos by NPR commentator Harry Shearer, as a corporate trainer who explains that copy-machine jams can be "an opportunity, a problem or a crisis," and Joshua Raoul Brody as the computer wizard in the firm's basement.

Of course it will cross your mind, as it crossed mine, that we think a little differently about office work in America right now than we did before Sept. 11. These sardonic fictional infodrones are not much different from many real-life office workers who rescued each other, or sacrificed themselves trying to, last Tuesday. Josh's predicament in the haiku tunnel may pale by comparison, but unlike his trashed apartment or his emotional immaturity, that really isn't his fault.

Shares