As the United States struggles to put together a coalition against world terrorism, it is being forced to take a crash course in the topsy-turvy politics of the Middle East, where yesterday's enemies may be tomorrow's friends. And one of the most intriguing players -- and a potential U.S. strategic partner -- is a state that just a few years ago was one of America's most implacable enemies: Iran.

In an act reflecting a convergence of U.S.-Iranian interests -- not the first such overlap in recent years -- the Iranian government gave tacit support to the United States' efforts to target Osama bin Laden, whom the Bush administration has described as the prime suspect in the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center. President Mohammad Khatami has reportedly signaled to the U.S. that his government would not oppose military strikes against specific targets in Afghanistan.

Iran's support for U.S. action is highly qualified. But the fact that it signed on at all to Bush's campaign against terrorism opens the possibility of a thaw between the two nations.

Mention Iran to the average American and what comes to mind is the grim face of the Ayatollah Khomeini denouncing America as "the Great Satan" and the humiliating, 444-day national ordeal that ensued after Islamic revolutionaries stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. But the image of Iran as the ultimate anti-American Islamic state is misleading. Times have changed. Iran is by no means a free and open society, but it has made significant strides toward democracy. It has a relatively large and comparatively Westernized middle class and a complicated political situation that includes a strong moderate faction as well as fundamentalist clerics. Iran is not an Arab state: About half of Iranians are Persians, ethnically distinct from Arabs and heirs to a great ancient empire. This distinction cannot be ignored when assessing Iran's political and cultural realities.

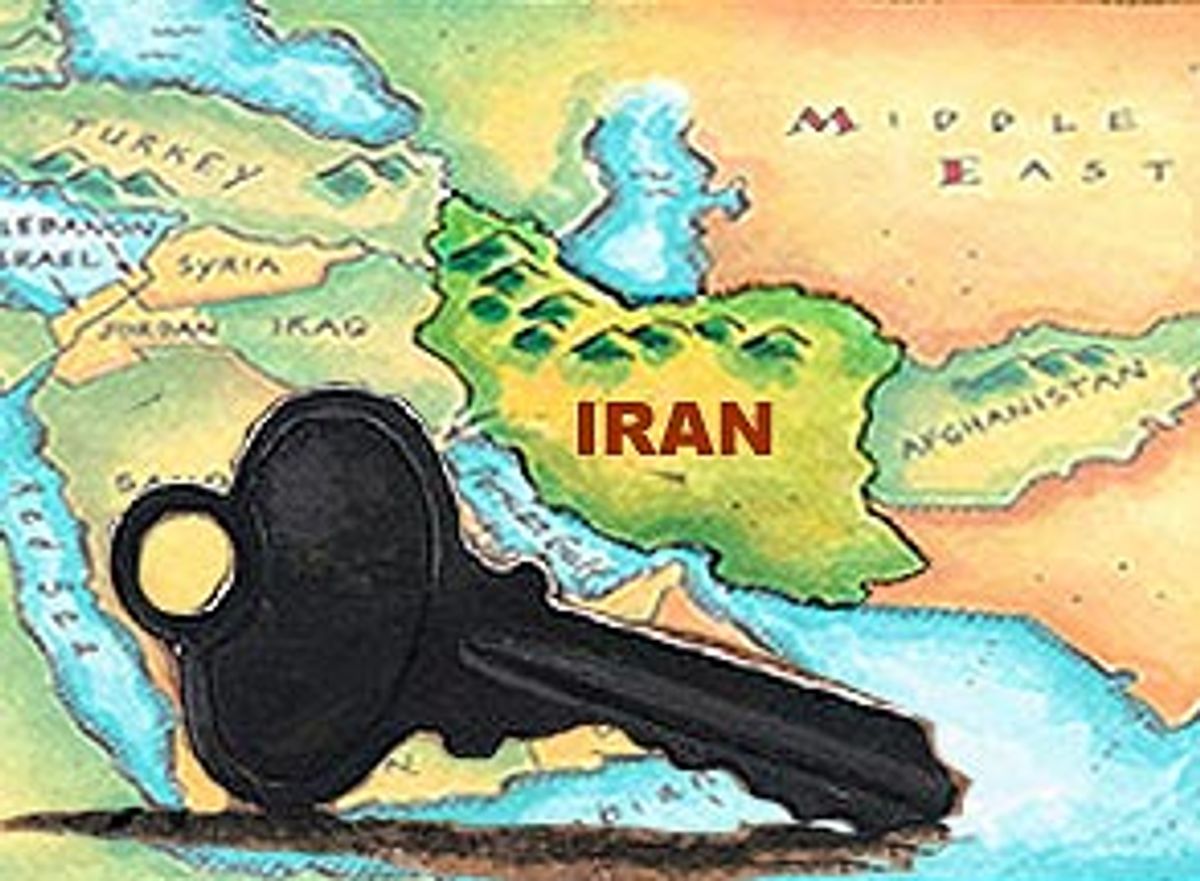

And it is strategically vital. Slightly larger than Alaska, it is the largest Middle Eastern country after the vast, empty Saudi Arabia, bordering Iraq, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan. It fronts the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus and has the longest coastline on the Persian Gulf of any nation. It is the third biggest oil exporter in the world, after Saudi Arabia and Norway. At 66 million, its population -- mostly under 30 -- puts it in Egypt and Turkey's class as a regional heavyweight.

The United States and Iran have not had diplomatic relations since 1979, and relations between the two nations remain chilly. But some experts argue that in the current crisis, America can no longer afford not to cultivate Iran. In their view, shared interests could pave the way to cooperation now and improved relations in the future.

Graham Fuller, former vice chairman of the National Intelligence Council, a U.S. government think tank, says that there's an "inexorable pressure" on the United States and Iran to reach rapprochement. "Washington now understands that the costs of not dealing with the most powerful power in the region are too expensive," says Fuller. Pointing out that embracing Iran could help erase the perception that the U.S. is antagonistic to the Muslim world, where U.S. policies have invariably collided with Islamic groups, Fuller says, "At some point, it behooves us to get along with some Islamist regimes that are moving towards fairly moderate policies."

How rapid is that movement? "Iran probably has made more progress towards democratization in the past five years than any other country in the Middle East," Fuller says. Noting that Iran is probably the most liberal and stable Islamic state in the world, Fuller says, "One of its signal features is its diversity -- violent and peaceful, democratic and autocratic, modernist and traditional." He cites "ideas developing in Iran about relationships between Islam and democracy and secularism" as examples of "fresh thinking that's not coming from elsewhere." These new ideas could be crucial in the future, Fuller believes.

Iran is clearly key to maintaining the balance of power both in the Middle East and central Asia. America and Iran come down on the same side of the key issues: containing Iraq, stabilizing Afghanistan, stopping the flow of drugs from Afghanistan and keeping the Persian Gulf open to oil shipments.

The terrorist attacks brought those shared interests into greater relief. Within days of the attacks, Iran sealed its 562-mile border with Afghanistan, fearing a mass exodus from Afghanistan into Iran. While clearly taken in self-interest, Iran's move may make it harder for supporters of Osama bin Laden to escape Afghanistan.

Iran, like Russia, has long been a supporter of the Afghan resistance movement and would be happy to see the Taliban fall. In 1999, Iran almost went to war against the ruling Afghan religious party when Taliban forces killed eight Iranian diplomats and a journalist after capturing a Shiite town in southwestern Afghanistan. (Iran is a Shiite nation; the Taliban are an extreme fundamentalist Sunni sect.)

"To the Iranians, the Taliban is by far a graver threat than the United States," says Robin Wright, author of "The Last Great Revolution: Turmoil and Transformation in Iran" (2000). "They really worry about the Taliban. They think they're barbarians because of the way they treat women, among other things. When you get the leadership to talk about how dangerous the Taliban is, then you know it permeates society."

But shared interests only go so far. While President Khatami was telling the U.S. that it would not oppose targeted strikes into Afghanistan, the nation's religious head and supreme leader was blasting America. In a speech on Iranian national television Wednesday, Ayatollah Ali Hoseini-Khamenei said the United States was "not sincere enough to lead an international move against terrorism," citing U.S. support for Israel as a key obstacle to Iranian participation in the U.S-led coalition now being assembled. He said Iran would offer "no help ... in an attack on suffering, neighboring, Muslim Afghanistan." Khamenei indicated that Iran is likely to oppose a U.S. ground war in Afghanistan.

Iran has strategic fears that will limit its role in any action against Afghanistan. "Iranians would like to see a change of regime in Kabul, but there are other concerns," says Shaul Bakash, professor of history at George Mason University and a specialist on modern Iranian politics. "The prospect of U.S. troops in Pakistan, Afghanistan and possibly the central Asian republics feeds Iran's perennial fears of encirclement."

Nor does Iran plan to share intelligence with the U.S. "It seems that the expectation that Iran would join or cooperate or share intelligence with the United States even is not going to happen now," Bakash says. "In his speech the leader specifically said they won't share intelligence. That's significant."

The U.S. still has major differences with Iran, as well. The Iranian government continues to call for the destruction of the state of Israel. And Iran remains on the State Department's list of states that sponsor terrorism, thanks largely to its sponsorship of Hezbollah, a Lebanese-based Shiite group that led the successful war against Israel's 18-year occupation of southern Lebanon. Among its numerous violent acts, including bombings and the taking of hostages, Hezbollah bombed the Marine barracks in Beirut in 1983, killing 241 Americans, as part of its campaign to drive the U.S. out of Lebanon. Whether Hezbollah at this point should still be considered a terrorist, or merely militant, organization is a point of controversy: the Christian editor of Lebanon's leading newspaper has declared that it should not, arguing that it is now a legitimate political party and social welfare network that is an integral part of Lebanese society.

Fuller acknowledges that Iran continues to support Hezbollah and smaller terrorist groups, but says that Hezbollah has moved away from terrorism since it drove the U.S. and Israel out of Lebanon. "They haven't really been engaged in terror attacks in six or seven years, while they've become fully integrated into the Lebanese government," says Fuller. "So yes, Iran still supports them, along with Syria, but is that going to be determinative in our diplomacy? We have to decide whether America's geopolitical interests are larger."

The United States imposed sanctions against Iran in 1996 when Iran attempted to acquire biological, chemical and nuclear weapons. In the words of the Iran-Libya Sanctions Act, "The efforts of the Government of Iran to acquire weapons of mass destruction and the means to deliver them and its support of acts of international terrorism endanger the national security and foreign policy interests of the United States and those countries with which the United States shares common strategic and foreign policy objectives." Iran is one of several nations, including India and Pakistan, that have been sanctioned by the United States for acquiring or attempting to acquire such weapons. (Sanctions against India and Pakistan were lifted after the terror attacks, to reward them for joining the anti-terror coalition.)

If the sanctions have been the greatest obstacle to improved U.S.-Iran relations, the looming clash between the West and Islam has the potential push the two nations even further apart. Despite President Bush's assurances that the U.S.'s fight is not with Islam but with terrorists, the perceived need to uphold Muslim brotherhood -- or at least political and strategic brotherhood -- may drive Khamenei and the religious hardliners who run Iran away from possible detente.

"The Iranian leader has posited himself as the spokesman for Muslim interests, so it's difficult for him to just stand aside," Bakash says. "He fancies himself as a leader for Muslims worldwide. He believes he speaks to issues that resonate with Muslims. That helps explain the very unyielding stand Iran has taken against the existence of the state of Israel. If Iran continues to take the stand it has against U.S. military action in Afghanistan, and the United States makes good on its position that you're either with us or against us, relations between the U.S. and Iran could even deteriorate as a result of this crisis."

In the face of Bush's declaration that countries must choose sides between America and terrorists, Iran defiantly continues to walk a third path -- as it has over much of the last 20 years. "It is not that anyone who is with you is against terrorism and those who are against you are for it," Khamenei said in response to Bush's ultimatum. "We are neither with you nor with the terrorists."

The United States and Iran have a 50-year history of mistrust, going back to a U.S.-backed coup that toppled Prime Minister Muhammad Mussadegh in 1953. As usual in the region, the main issue was oil.

Mussadegh was a charismatic nationalist who led a popular movement to nationalize the British-owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. He grew so popular that Shah Reza Pahlavi was forced to appoint him prime minister in 1951. The growing rift between the Shah and Mussadegh climaxed in 1953, when Mussadegh forced the Shah from the throne. A week later, revolts sponsored by the CIA and British intelligence successfully reinstated the Shah, and Iran remained a dictatorship until the 1979 revolution. The rule of the Shah and his dreaded secret police, Savak, was harsh.

In "The Last Great Revolution," Wright argues that the Iranian Revolution was not so much a religious as a political revolution which aimed, like the French or Russian revolutions before it, at expanding freedom.

"Iran's revolution was always a part of the broader global expansion of democracy," she says. "Iranians twice before in the 20th century had tried evolutionary political tactics to end a monarchy dating back two and a half millennia. They turned to revolution in 1979 out of frustration. The revolution was hijacked by the clerics. But at the end of the day Iranians are still searching for some system that allows them that freedom but is compatible with an Islamic culture."

But also like the French and Russian Revolutions, Wright argues, the early years of the Iranian Revolution were frenzied and often out of control. That frenzy often took the form of anti-American zeal. Indeed, the relationship between Iran and the United States was among the many casualties of the revolution. Relations between the two countries hit a new low when Iranian militants seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in 1979 and held 52 people hostage for over a year. The hostages were released on Jan. 20, 1981, hours after Jimmy Carter's term officially ended and new U.S. President Ronald Reagan had been sworn in.

In 1983, the Iranian-backed group Hezbollah was linked to the bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut, which killed 63 people, and the bombing of the Marine barracks at Beirut International Airport, which killed 241 U.S. military personnel. Over the next decade, more than 100 people were taken hostage in the Middle East, many of them by Iranian allies. As a response to the new Iranian threat, the United States backed Iraq's secular government, headed by Saddam Hussein, in its bloody eight-year war with Iran.

But by the late '80s, relations had improved. Iran accepted the terms of a cease-fire negotiated by the United Nations, and used its leverage to help secure the release of Western hostages in Lebanon. Tehran "made overtures to Western capitals," according to Wright, and ended a period of relative isolation by bolstering trade. "The revolutionary fervor," she writes, "looked as though it was about to break."

Around that time, American foreign policy in the Middle East changed dramatically as well. In 1991, Iraq invaded Kuwait and suddenly became America's new Public Enemy No. 1. An informal, uneasy alliance began with Iran. While Iran did not object to the U.S. and its allies' presence in the Gulf War, it did not offer troops or explicit support to the Gulf War effort.

"There certainly was a coincidence of interests during the Gulf War," says Bakash. "Though they did not join actively, they didn't mind seeing Saddam Hussein get clobbered. They were very firm in declaring the occupation of Kuwait unacceptable."

The balance of power shift in the Gulf had moved the United States uneasily closer to Iran.

Meanwhile, what Wright calls the "Second Republic" phase of the revolution began. The Ayatollah Khomeini, the revolution's charismatic leader who had returned from abroad after the Shah's ouster, died in 1989. In the wake of his death, a movement for political and social reform developed strength. This started with the election of President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who embraced more assistance from and contacts with the West, and culminated in the election of reformer Ali Mohammed Khatami-Ardakani as president in 1997.

Since Khatami's election, hopes for reestablishing a diplomatic relationship with Iran have swelled. Soon after his election Khatami made waves in an interview with CNN, when he said that he "respected" the United States and advocated "dialogue and understanding between two nations, especially between their scholars and thinkers." Soon after, limited cultural exchanges between Iran and the U.S. began.

Despite this détente, however, throughout Khatami's first term as president it was clear that the opponents of reform remained strong. Khatami and the moderates had little control over the military and intelligence services, which assassinated some opposition figures and closed many reformist publications. "We were all hopeful that Khatami would do something," says Wright. "But we've all found that he's not the person who's going to make the transition. He hasn't had the willingness or ability to overcome the hard-liners. A lot of people are disappointed."

Still, the rough path toward a renewed diplomatic relationship continued. In March 2000 Secretary of State Madeleine Albright extended an olive branch of sorts. She acknowledged America's role in overthrowing Mossadegh in 1953 and supporting the Shah, who "brutally repressed political dissent." And she slammed America's "shortsighted" support of Iraq during its war with Iran in the 1980s.

"As in any diverse society, there are many currents swirling about in Iran," Albright said. "Some are driving the country forward; others are holding it back. The question both countries now face is whether to allow the past to freeze the future; or to find a way to plant the seeds of a new relationship that will enable us to harvest shared advantages in years to come, not more tragedies."

But neither the United States nor Iran has reached internal consensus on how and if negotiations over renewing diplomatic relations should continue. Khatami's recent reelection in June 2001, with an even greater majority of reformer victories in the parliament, has sparked even more debate over whether the time is ripe to intensify the relationship. Some members of Congress, including Ohio Republican Robert Ney, have signaled a desire to move toward reestablishing diplomatic ties with Iran.

But some in the United States believe that Iran still isn't ready. James Phillips, research fellow for Middle Eastern affairs at the Heritage Foundation, says that there's a "perception in the West that things are going great, the reformers are winning elections and making the right diplomatic noises. But real power is still in the hands of Khamenei." Phillips says hard-liners like Khamenei still have the potential to eradicate the reformers' gains over the past decade simply because they retain the most levers of power.

"Until Iran's internal politics are resolved it's dangerous to reach out to moderates," Phillips says. "It's counterintuitive, but a hard-line U.S. policy strengthens the moderates because it allows them to improve their grip on power by pointing to the continued bad management of everything else by the hard-liners. Renewed diplomatic relationships between the U.S. and Iran now could end up strengthening the hard-liners' hand."

But others articulate a different vision of the United States' interests and Iran's prognosis.

The National Intelligence Council's Fuller, while acknowledging that serious roadblocks remain, thinks that at this moment "there are some good reasons to hasten the solution." As for the argument that the hard-liners in Iran might twist a renewed diplomatic relationship with the U.S. to their advantage, Fuller says they're eventually doomed anyway: "Time is clearly on the side of the reformers. Most of the hard-liners know that the end is coming."

But is Iran too unstable? "I would not call it an unstable state," Fuller replies. "There haven't been any coups nor any un-democratic changes in government since 1979. If you say that they have a divided government, then welcome to the world -- there are all kinds of divided governments around the world."

One reason for optimism about a détente with Iran is the changing attitude of its people. While the leadership remains divided, there's strong evidence of popular support for renewing ties with America. Recent cultural exchanges like soccer games and wrestling matches between Iran and the U.S. were sold out, and the Americans were cheered in both victory and defeat.

Nor are the people enamored of religious rule. Phillips says that the combination of economic depression and widely perceived mismanagement by the mullahs (the Shiite clerics who run the country, via their control of the judiciary and the military) have even alienated key allies in the revolution. "Even the urban poor, who supported Khomeini's revolution, are becoming fed up because the mullahs control everything and have done such a horrible job. There's a population explosion, job and housing shortages, declining living standards and more. The mullahs were temporarily rescued by the rise in oil prices, but they can't depend on that forever."

A key reason for the declining popularity of the mullahs is the fact that the majority of Iranians are now under 30 years old, while the older mullahs are often perceived as out of touch. "It's often said that the mullahs are making Iran a nation of atheists, because they're subverting the authority of Islam," says Phillips. "For example, the mullahs always use the Shah's behavior before the revolution or the United States' behavior in the same period of how bad they are. But the examples are no longer effective because the young don't know the Shah or the United States."

And if they do know about the United States, Iranians don't necessarily see it as the Great Satan. Western reporters in Iran have frequently noted the predominance of satellite dishes in Tehran, and the inroads of the global consumer culture: name brands everywhere and American sport jerseys on the streets.

But Michael Jordan T-shirts and reruns of "Dynasty" may not be enough to bridge the gaps between the two nations. "The obstacles are pretty formidable," says Bakash. "My impression was that the Bush administration was eager to be able to relax sanctions and open up a dialogue with Iran. But there have been moments like this before, and they have fallen apart.

"There are people in Iran and the U.S. who would like to break this deadlock. But I also think there are real obstacles. Sanctions, Hezbollah and the peace process [between Israel and the Palestinians] are the big issues. If you listen to the speeches [Ayatollah Khamenei] has made over the years, he sees a lot of negatives, and few positives, to normalizing relations. The leader himself is not persuaded."

The major immediate practical obstacle, says Bakash, are sanctions. "One of Iran's conditions is the lifting of sanctions. I think the Iranians have said so implicitly in the past, and more directly recently, that relations or negotiations are not conceivable under the gun of sanctions."

Regardless of the immediate future of U.S.-Iran relations, Robin Wright believes that in the long run, Iran and its yet-unfinished revolution may point toward a possible Third Way for Islamic societies -- a welcome possibility since Sept. 11. "Iran may be the trendsetter," she says. "Here's an Islamic country where you have women who are vice presidents and members of parliament. This is where women can be nobody and run for office. And that's sometimes in spite of the clerics' wishes. The fundamental question Iran is dealing with is, 'Do you make it more of a republic than an Islamic system?' It's a microcosm for what's going on in other parts of the Islamic world. Everything you see is related to this challenge to modernize, and how to come to grips with individual freedom in a system with a religion that literally translates as 'submission.' The Western world is now democratized. So now we have to deal with the Islamic world. Iran created a model. Not one that's going to be emulated, but it opens up the debate for future Islamic revolutions."

Shares