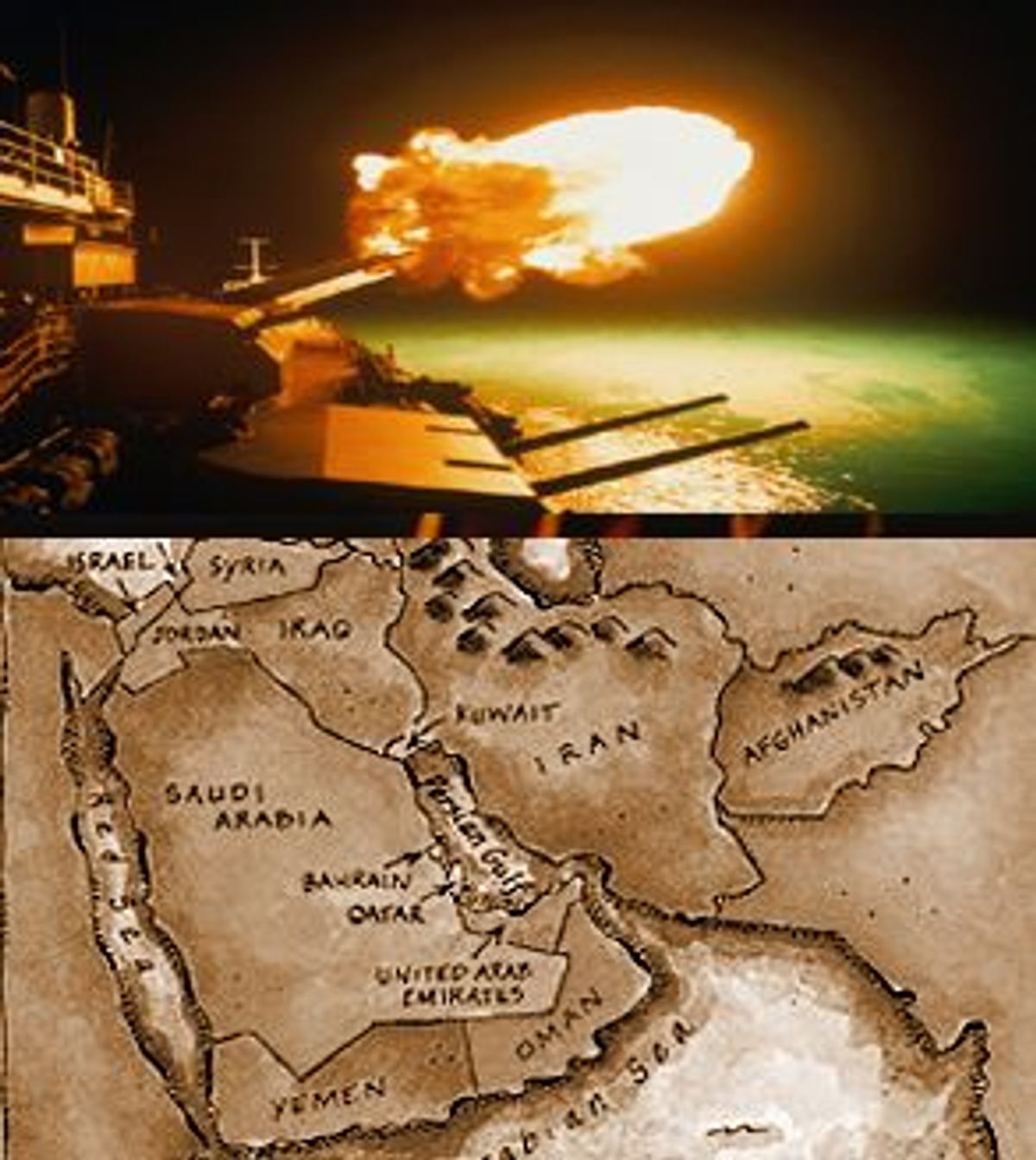

In December 1998, after Iraqi president Saddam Hussein had once again refused to allow United Nations weapons inspectors to do their job, the United States and Britain responded with a four-day bombing campaign over Baghdad.

The timing was tricky -- just before the commencement of the Muslim holy month, Ramadan. Sensitive to the implications, the allied forces were careful to end their bombing raid before Ramadan, hoping to avoid provoking unnecessary anger from Muslims around the world.

But that didn't stop two smiling U.S. servicemen from posing for a photographer as they scribbled "Happy Ramadan" on a missile bound for Baghdad. The photograph, capturing America's worst kind of stereotypical disrespect toward Islam, was printed in Arabic newspapers throughout the region and broadcast over and over on Middle Eastern television.

"That image was shown nonstop," recalls Chris Toensing, editor of the Middle East Report, who was living in Egypt at the time. "The damage was done as far as public opinion."

The image has been quickly forgotten by the West, but lingers on with many Muslims and Arabs. Is it any wonder then that so much distrust has built up over the last decade between the two cultures? The photograph of the sacrilegious bomb offers a shorthand explanation of why the American-led war on terrorism is being viewed so skeptically by many Arabs -- and why Arab rulers, even if they despise Osama bin Laden, cannot embrace the cause too openly.

American allies such as Germany, France, Spain, Italy and Russia have all rushed forward to support the military strikes taking place in Afghanistan, but crucial leaders from the Arab world have remained conspicuously quiet. Regimes in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan and Syria, among others, are all anxious for their own political reasons to snuff out bin Laden's terrorist network, as well as to cozy up to Washington. But they must first test the waters of public opinion. And the gap between the politics of the streets and the politics of government in the Middle East is often vast.

"We don't think much about Arab public opinion," notes Ali Abunimah, vice president of the Arab-American Action Network. That's because, he says, the region is dominated by authoritarian and totalitarian rulers who have no interest in allowing polls to take public snapshots of the populous.

With no true democracies among the Arab nations, public opinion cannot directly change state policy. Governments, however, ignore the will of the people at their own risk. "The regimes are autocratic, but that doesn't mean they're stable," notes Abunimah. "They need to pay very close attention to public opinion."

If Arab or Muslim opinion turns sharply against the war effort, (or "this so-called war" as Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld labeled it Sunday), governments may have no choice but to pull back or soften their support.

"That's the real joker in the deck," says Toensing. "How far will governments in the region be willing to stick their necks out for the United States?"

Similar concerns were raised 10 years ago during the Gulf War. Skeptics suggested an Islamic backlash at home could mushroom and threaten the stability of moderate Arab regimes that chose to cooperate with America. Instead, the coalition held together and the war itself proved to be a brief one.

But events since Operation Desert Storm have only hardened Arab distrust of the United States. Among the growing list of grievances, Toensing points to continued sanctions against the people of Iraq. Many Muslims, he says, blame widespread Iraqi malnutrition on the sanctions. The 1998 missile attacks on a Sudan pharmaceutical factory ordered by President Clinton further inflamed passions -- many Muslims (and many non-Muslims) say there's little proof to support the claim that the factory was used by bin Laden for creating chemical weapons.

Aside from the "Happy Ramadan" photo from Operation Desert Fox, the continuous U.S. and British patrolling of the No Fly Zone in northern and southern Iraq is another irritant. Iraq's Saddam Hussein claims more than 1,000 people have been killed by the strikes. The U.S. and Britain dispute those numbers, but the charge carries resonance with many Muslims.

Combined with what many consider to be America's broken promise from the Gulf War to pressure Israel to negotiate a peace settlement, the accumulation of incidents means "there is a lot more cynicism this time around," says Abunimah. "They're asking, 'Do you really mean it?'"

Toensing agrees: "The level of trust [among the local population] towards the United States is virtually nil. And the level of trust towards their own governments isn't much higher."

That distrust will likely increase if civilian casualties mount from the missile strikes.

"I have no idea how much collateral damage the coalition could withstand, but there is probably pressure being exerted by Arab nations on the United States to limit the bombing to the furthest extent possible," says Toensing. "Fear of casualties will definitely limit the United States' military options." And if the United States broadens the attacks to include terrorist targets in other Arab nations, "it loses all of its Muslim allies," warns John Voll, professor of Islamic history at Georgetown University.

Meanwhile, the Powell Doctrine, named after Secretary of State Colin Powell, which states American military is used only when its full power can be unleashed, has also been shelved. That's because unlimited bombing would virtually level the Afghan capitol of Kabul, incite further unrest among the masses in the region, and knock more allies out of the coalition.

With public opinion so important, protests throughout the Arab region in coming days will be watched carefully as a measure of public sentiment. But be warned, Middle East street theater is not always what it appears to be.

"Egypt actually would welcome some level of popular dissent to show its courage, its worth to the United States," notes Vickie Langohr, assistant professor of political science at Holy Cross College.

She's referring to the time-honored tradition among Arab regimes of using pictures of civil unrest at home to prove to the United States that the government's hands are tied, and that Washington should be grateful for all that the regime is doing for them.

Notes Toensing, "Maximum cynicism is justified."

Shares