For years I've had this ritual. Every morning, I log onto my computer, check for desperate e-mails from desperate editors, then open the bookmark for Rickey Henderson's career stats. I scroll down to the runs-scored column and see if, based on last night's action, the number has inched closer to 2,245.

It's the kind of guilty pleasure only a baseball fan can understand. Baseball is the only sport where stats really resonate, where you can forge a connection with your favorite player based on a page full of numbers. It was about eight years ago that I first noticed that Henderson had a legitimate shot at breaking the longest-standing major hitting record on the books: Ty Cobb's mark of 2,245 runs scored. And this is the week that he finally did it.

Being a Rickey Henderson fan is a guilty pleasure in itself. Friends -- smart baseball fans, some even baseball writers -- view any mention of my Rickey Watch as an open invitation to trash him. "He is the biggest jerk," goes the chorus. No, it's not personal -- he didn't refuse to sign an autograph or blow off an interview. It's simply a style thing: '80s retro notwithstanding the snatch catches, the wraparound sunglasses, his "I am the greatest of all time" speech, they simply rub people the wrong way.

But as Ty Cobb -- or was it Freud? -- once said, "It ain't braggin' if you can back it up." Say what you will about Henderson's 'tude, he walks the walk. When he burst onto the scene with the Oakland A's in '79 (around the time that Bill James earned a place beside Henry James on my bookshelf), he was the epitome of the postmodern baseball player. His genius was subtle, and to appreciate it took an aficionado's eye -- it was the baseball equivalent of touting Tobe Hooper as an auteur. Henderson's batting average may be average (.280 career), but look at that .403 on-base percentage. Sure he steals bases (1,395 to date) better than anyone ever, but he'd be a Hall of Famer without a single sack swiped. He was, inarguably, the best leadoff man ever, and I didn't have to read about him in Total Baseball, I could watch him on the Game of the Week. The Ali-like swagger was merely a bonus.

And for a little while, I got to see Henderson every day, his rock-solid physique poured into skintight Yankee pinstripes in a way that surely made Joe DiMaggio blush. I relished the way he worked a pitcher, sinking into his Eddie Gaedel crouch, shrinking further as the high fastball approached the plate. And then, inevitably, the desperate pitcher would lay in a 3-0 fastball, and Rickey would uncoil and drive the ball into the left center field bleachers. Four pitches, 1-0. And the Rickey Rally -- a walk, two stolen bases and a sacrifice fly -- was purist baseball at its best. Scoring runs, after all, is baseball's bottom line, and no one's better at it than Rickey Henderson.

In 1985, playing for the Yankees, he had one of the great seasons in baseball history, scoring 146 runs in 143 games. And then he lost the MVP to the guy who drove him in, the paler and more palatable Don Mattingly. When Henderson moved on to Oakland, Toronto and points west, I dutifully followed his exploits in the morning's box scores.

His stay at Shea? It wasn't an easy time to be a Henderson fan. The sports-talk callers were ready to burn him in effigy for allegedly playing cards in the Mets clubhouse with Bobby Bonilla after he was lifted from Game 6 of the 1999 National League Championship Series. Everyone seemed to forget that the Mets wouldn't have even made the postseason sans Henderson. Then early the next spring, Rickey broke into a home run trot only to have the ball bounce off the wall. Rickey got no further than first. "I hit it out, but it didn't go out," he said sheepishly, only hours before he got his walking papers.

That goes with the territory. Ruth drank. Cobb was a virulent racist. Henderson marches to the beat of his own inner Elvin Jones. Rickey talks to himself. ("That's not how Rickey swings.") He talks to his bats. ("Which one of you bad boys got some hits in you?") He talks about himself in the third person. ("This is Rickey calling on behalf of Rickey.") Hell, he even throws left and bats right.

Indeed, Henderson has become something of a fin-de-millennium Yogi Berra. During his first go-round with the San Diego Padres, he was looking for a seat on the team bus and teammate Steve Finley said, "Sit anywhere you want, you got tenure."

"Ten years? What are you talking about? Rickey got 16, 17 years." The bus broke up.

Another Rickey story. When he hooked up with the Seattle Mariners last year, Rickey is said to have approached John Olerud, who had once suffered a brain aneurysm, and asked about his unusual practice of wearing a batting helmet in the field. Henderson says, "I used to play with a dude in New York who did the same thing."

"That was me," said Olerud, who was Henderson's teammate with both the Mets and the Blue Jays. Good story. Widely reported. And completely untrue -- concocted by a visiting player who had run out of hot-foot victims.

But apocryphal or not, it's the kind of incident that Henderson's critics cite as proof of his stupidity or his self-absorption. "How on earth Rickey Henderson sustained such a tremendous career," added one Internet critic, as a footnote to the Olerud fable, "while acting like the self-centered idiot that he is, I have no idea."

So maybe it's for the best that, at 42, Rickey's playing out the string quietly, chasing ghosts in silence. Earlier this year, after starting the season in AAA, Rickey broke the career record for walks, the last career mark held by Babe Ruth. Think about that. Rickey has. "Ahhh, that's something, that's a really big record," he told me a few years back. "As a leadoff hitter and a guy who steals bases and creates stuff on the base paths, really I don't think I'm supposed to be in that category. Most of them that are getting all the walks are the big power hitters, the big home run hitters." Walk Ruth? Sure. Grover Cleveland did just that with a one-run lead in the ninth inning of the seventh game of the 1926 World Series. And Ruth killed the Yankees' chances by getting thrown out trying to steal second. But walk the game's greatest base stealer? Most pitchers would rather get traded to Milwaukee. But walk him they do -- 2,141 times and counting.

And as the season wound to a close, Rickey Henley Henderson found himself oh-so-close to both 3,000 hits (in itself a virtual invite to Cooperstown) and Cobb's runs record, a mark that eluded Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Hank Aaron and Pete Rose. The biggest Henderson headlines of the summer came in late August when Milwaukee manager Davey Lopes (a former Henderson teammate) ran out to second base and confronted Henderson after Rickey had stolen second in the seventh inning with the Padres up 12-5. "Stay in the game you're going down," fumed Lopes. "We're old school," Lopes said later, ignoring the fact that he had done the same thing in exactly the same situation seven times in his career. "There are some things you just don't do."

Caught between the old school and the new, embraced by neither, it makes perverse sense that as Henderson approached a 73-year-old milestone, the nation's attention was focused elsewhere. On Cal Ripken Jr's farewell tour. Or Tony Gwynn's. Or Barry Bonds' home run chase. Or recent national events. When Henderson tied Cobb on Thursday, Sports Center buried the story behind Bonds' failing to tie the home run record and Roy Oswalt's groin injury, and the feat merited but a single joke ("One more run and he gets a salad named after him." Get it? Cobb salad?). And coming on the same night as Bonds' 70th homer, Rickey's record-breaker was again an afterthought. Ditto for his 3,000th hit on Sunday, overshadowed by another Bonds dinger, and Gwynn's swan song.

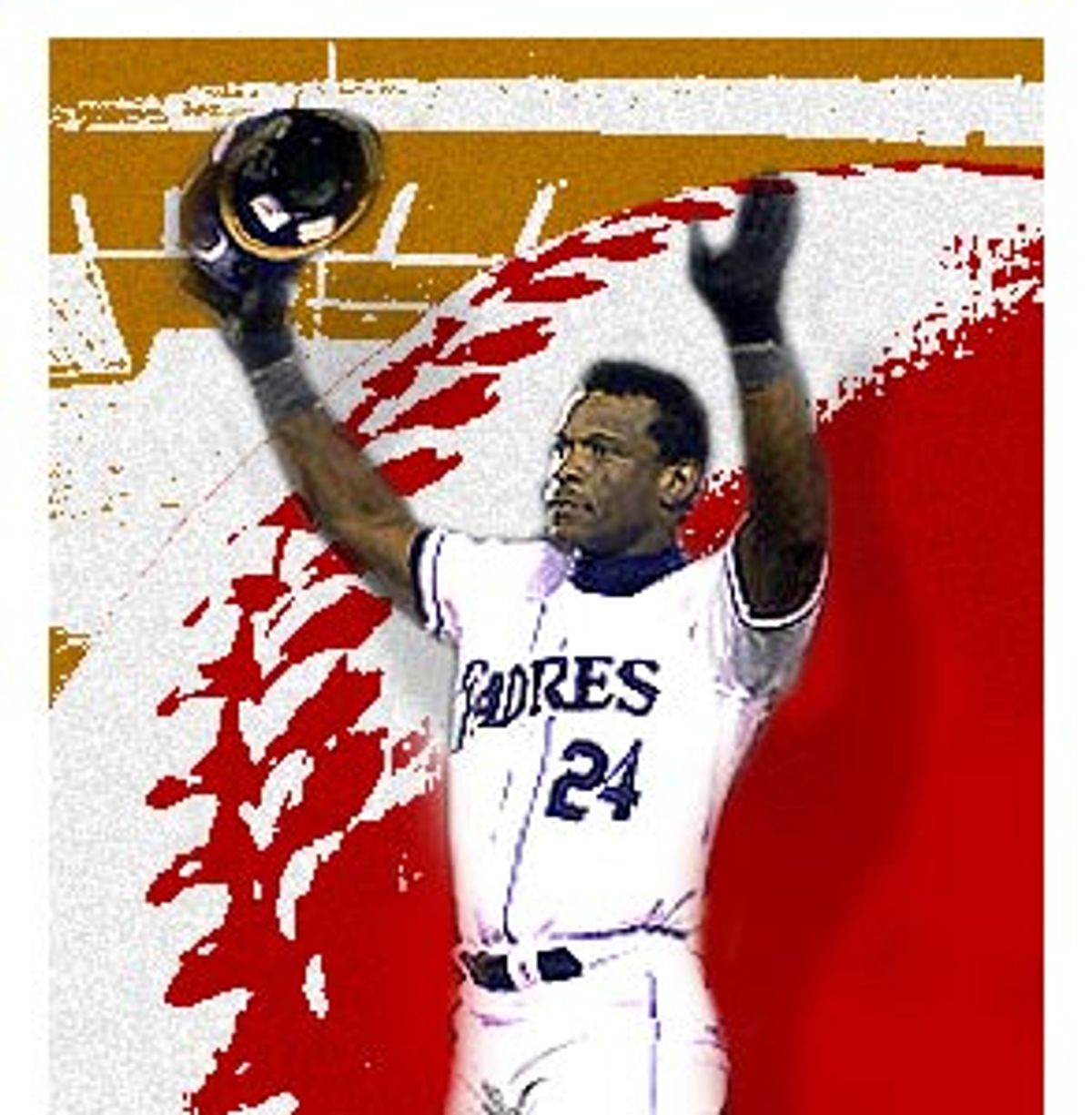

But it works for me. Rickey Watch has always been a solitary diversion, a cyber-vigil for one of the handful of players in the big leagues older than me. And as I watched him, live on tape, slide into home after the record-breaking home run, and lift the gold-plated commemorative bag over his head, I remembered a day at Yankee Stadium a few years ago, with Rickey in town with the A's. The Rickey-o-meter stood at exactly 2,000 then, and I discovered that my suspicions were correct -- I was not alone among the faithful. "Ten years ago, when I was asked the question, 'What's the most important thing for you to do?' I always said scoring runs," explained Rickey with uncharacteristic seriousness. "A leadoff hitter's job is to come across the plate." No joking, no jaking, no jerking around, I could see in Rickey's eyes that he still had a score to settle. "You have a vision," he said, picturing the specter of Ty Cobb as clearly as Haley Joel Osment saw dead people. "He's in front of you. You can see it." I could too now as I watched 2,244 change to 2,245 and then to 2,246 and beyond.

Shares