After a meeting with military leaders at the Pentagon on Sept. 17, President Bush waxed old western, saying that he wanted "justice" for Osama bin Laden -- "there's an old poster out West, as I recall, that said 'Wanted: Dead or Alive.'"

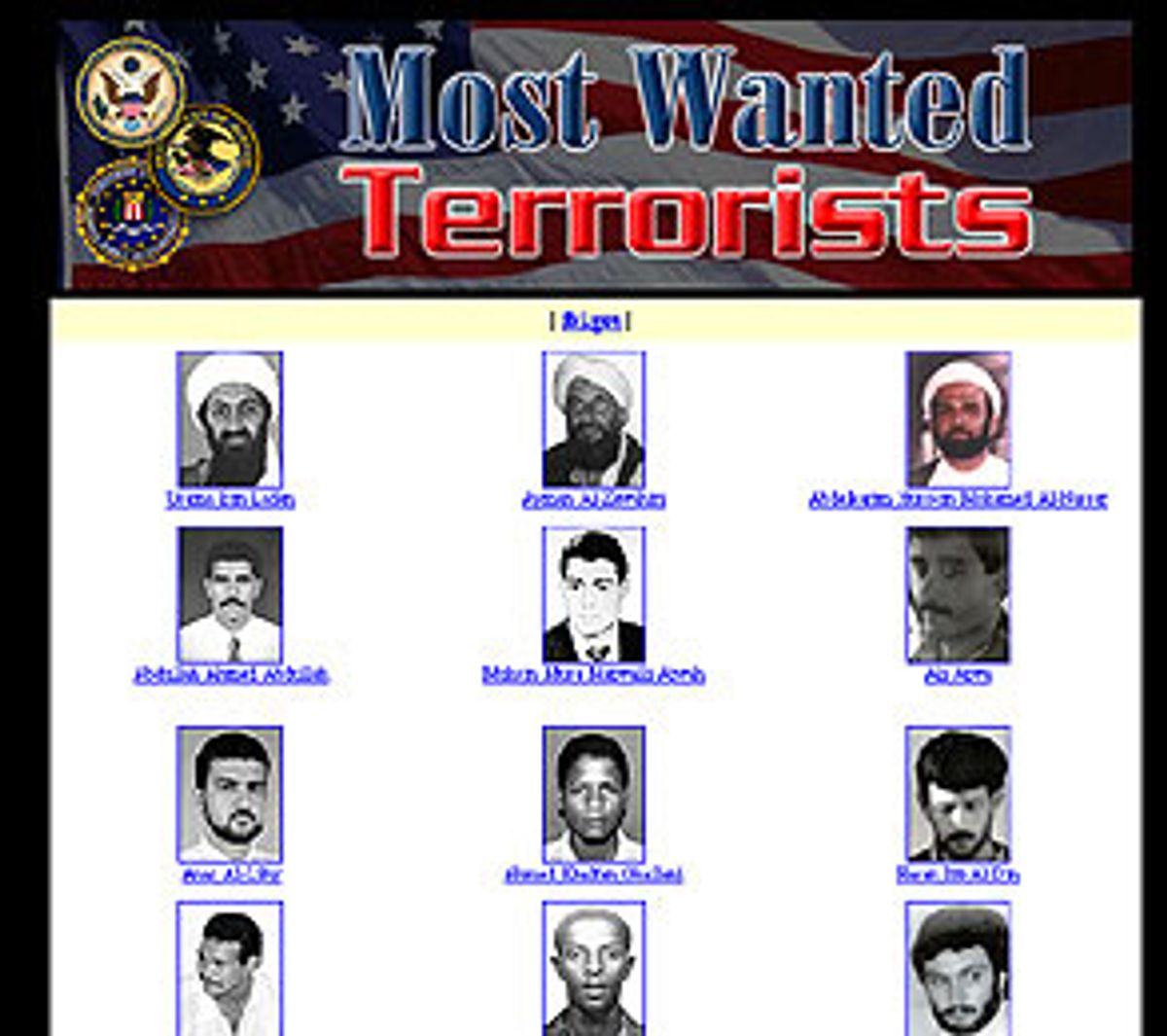

Though Bush has backed off the sheriff-like rhetoric since then, on Wednesday he and other administration officials stood in the FBI headquarters with three rows of wanted posters. Though the effort wasn't new, the publicity afforded it was, as Bush announced the creation of a list of the top 22 "Most Wanted Terrorists." Secretary of State Colin Powell added that the 22 individuals would also be publicized through the State Department's "Rewards for Justice" program, which offers financial compensation and relocation opportunities for individuals who provide tips to officials about either wanted terrorists or pending terrorist conspiracies.

"Terrorists try to operate in the shadows," Bush said. "They try to hide. But we're going to shine the light of justice on them."

At the Wednesday announcement, FBI director Robert Mueller rightly heralded the success of the agency's Ten Most Wanted list, which publicizes fugitive criminals, largely American ones, throughout the globe. Initiated in 1950, the program has listed 467 individuals, of whom 438 have been captured. "Nearly one in three have been apprehended through a tip from a private citizen," Mueller said. But the Rewards for Justice program and other international efforts to capture terrorists have historically had only middling successes. Founded in 1984, the program has so far resulted in the known capture or detention of five terrorists. While those efforts invariably represent countless lives saved, the relatively small number ultimately imprisoned provides a window into how difficult these efforts have been in the past.

And while the global war on terrorism might change things dramatically, in the past the Rewards program has not sparked much energy with the international community. "It's much more complicated when you do it overseas, and when you're trying to bring these people to U.S. courts," says Steven Pomerantz, former head of the FBI Counterterrorism Unit.

This is not to say that the program doesn't work at all. "The guys in the diplomatic security bureau thought it worked or they wouldn't keep proposing it," says former State Department spokesman Jamie Rubin.

Powell said that in its 17 years, the Rewards for Justice Program has paid more than $8 million in 22 separate cases "to people who provided information that put terrorists in prison or prevented attacks." State Department spokeswoman Susan Pittman couldn't break down the 22 cases between number of terrorists apprehended vs. the number of incidents thwarted. And most of the information about the tips is, of course, classified.

Historically, Pomerantz says, Rewards for Justice has not been very successful because of a lack of international cooperation, though he stresses that that in no way means it should be discontinued. He hopes that the program's success rate will now change as the nation and the world pursue terrorists like never before. "Now we seem to be in a new time where we're much more serious about bringing these people to justice," he says.

Many of the individuals on Wednesday's list have been listed as "wanted" for years -- bin Laden has been on the FBI's Top Ten Most Wanted list and the Rewards for Justice list for the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. Three of the terrorists on Wednesday's list are wanted for a hijacking that took place more than 16 years ago. Fifteen of the 22 were already listed on the pre-existing "Rewards for Justice" wanted list.

On Wednesday, Mueller listed two international terrorists who have been apprehended through the FBI Ten Most Wanted list in conjunction with Rewards for Justice. They are Mir Aimal Kansi, who murdered two CIA employees in 1993, and Ramzi Yousef, one of the masterminds of the first attack on the World Trade Center that same year.

Yousef was conspiring to bomb 12 commercial airliners over the Pacific. But, Powell said, "his plot was foiled when an informant in Pakistan, alerted by State Department fliers describing Yousef and his role in the [World Trade Center] bombing, turned him in.

"We want to see this story repeated everywhere," Powell said.

That Rewards for Justice campaign to find Yousef proved successful after two years in which the State Department began to saturate the globe with posters, matchbooks, fliers and newspaper ads focused on Yousef and his role in the 1993 bombing. Yousef is serving a sentence of life in prison.

Powell said that the United States would publicize the 22 most wanted terrorists by "getting the word out about out Rewards for Justice program in fliers and other ways of reaching the public," including a Web site. (He initially gave an incorrect Web site address for the program, offering a dot-com suffix to the URL when in actuality it's dot-net.) The Web site, in fact, could help reach individuals in countries where the governments might not aggressively publicize or pursue the subjects on the list. According to Rubin, that's why the reward money was even offered -- "it's not designed for governments so much as it is for individuals," he says.

Three other terrorists are listed on the State Department's Web site as having been snagged as a result of the Rewards for Justice program: Khalfan Khamis Mohamed, who was found guilty by a grand jury in May for his role in the embassy bombings; Abdelmajid Dahoumane, who was apprehended by Algerian security forces in March for allegedly plotting an act of terrorism in the United States during the Millennium celebration; and Abdel Basset Ali Al-Megrahi, formerly the chief of airline security for Libyan Arab Airlines, who was convicted in January for his role in the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing and is in custody in a special Scottish court in the Netherlands.

In these instances, the program and international community worked together well. But there are also glaring examples of failure and the unwillingness of the international community to work to apprehend terrorists. Imad Fayez Mugniyah, one of the top 22 "Most Wanted Terrorists" presented to the world Wednesday, has been committing terrorist attacks against Americans since at least 1983, when he led the bombings of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut, which killed 16, and the U.S. Marine barracks, which killed 241.

Mugniyah has long been in Beirut, Lebanon, according to Pomerantz. But the Lebanese government has refused to assist in bringing him to justice for his role in the 1985 hijacking of TWA Flight 847 from Athens to Rome, which resulted in the murder of an American citizen, Robert Dean Stethem.

And it's not only the Lebanese government that has refused to hand over Mugniyah. In 1995, the FBI learned that Mugniyah was on a commercial airliner that was scheduled for a layover in Saudi Arabia. But at the last minute, the Saudi government -- against U.S. wishes -- denied the plane permission to land, and Mugniyah thus avoided capture.

The State Department's Pittman vaguely acknowledges that not everyone in the international community has been helpful in apprehending terrorists in the past. "Can more be done? Of course more can be done," she says. But foreign governments have been far more cooperative since Sept. 11, she says, pointing out the dozens of arrests and detentions made by police forces abroad. "I think that they have been more cooperative," she says.

The latest campaign also relies upon the participation of the news media as never before, coming as it does during a time of particular tension between the White House and the media. Bush issued a harsh rebuke to Congress on Tuesday for leaking classified material to the news media. And on Wednesday morning, National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice contacted several television network executives and requested that they not broadcast videotapes in the entirety featuring members of the al-Qaida terrorist network since the administration is concerned that the tapes may include secret messages for terrorist operatives.

No. 1 of the 22 is bin Laden, described as anywhere from 6-foot-4 to 6-foot-6, approximately 160 pounds, left-handed and with an olive complexion. The reward for bin Laden is $7 million -- $5 million from the Rewards for Justice program and another $2 million from the Airline Pilots Association and the Air Transport Association. He and 12 others -- Muhammad Atef, Ayman Al-Zawahiri, Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, Mustafa Mohamed Fadhil, Fahid Mohammed Ally Msalam, Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani, Sheikh Ahmed Salim Swedan, Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah, Anas Al-Liby, Saif Al-Adel, Ahmed Mohammed Hamed Ali and Mushin Musa Matwalli Atwah -- are wanted for their roles in the 1998 embassy bombings.

The FBI listing makes no mention of the Sept. 11 attacks; they instead focus on indictments from trials.

Abdul Rahman Yasin is wanted for his role in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. Khalid Shaikh Mohammed is wanted for his role in a mid-1990s conspiracy to bomb 12 commercial U.S. flights. Four of the fugitives -- Ahmed Ibrahim Al-Mughassil, Ali Saed Bin Ali El-Houri, Ibrahim Salih Mohammed Al-Yacoub and Abdelkarim Hussein Mohamed Al-Nasser -- are wanted for their roles in the 1996 bombing of the Khobar Towers U.S. military housing in Saudi Arabia. Mugniyah, along with Hassan Izz-Al-Din and Ali Atwa, are wanted for their role in the 1985 hijacking of TWA Flight 847.

One criticism of the Rewards for Justice program in the past has been that it has yet to include a Palestinian terrorist on its lists, even those who have killed Americans, whether tourists in Israel or diplomats. Wednesday's announcement did not change that.

Bush noted that "these 22 individuals do not account for all the terrorist activity in the world, but they are among the most dangerous -- the leaders and key supporters, the planners and strategists. They must be found. They will be stopped, and they will be punished." He went on to say that these men are just "the first 22."

"Now is the time to draw the line in the sand against the evil ones, and this government is committed to doing just that," Bush said, echoing his father's August 1990 promise that "a line has been drawn in the sand" against Iraqi President Saddam Hussein.

Shares