Every October, the Nobel committees emerge from the gloam that surrounds their deliberations and laurel the names of several brilliant scientists, a political figure or organization of world acclaim and, chances are, some author you've never heard of. To say "chances are" is to account for G|nter Grass' win in 1999, Seamus Heaney's in 1995 and Toni Morrison's two years before that. And it's to account for Sir Vidia Naipaul's win on Thursday.

Otherwise, the prize for literature has, over the past decade, given us such names to puzzle over as Gao Xingjian (2000) and Wislawa Szymborska (1996), names that an ordinary educated Anglophone couldn't have been expected to know prior to their association with the Nobel. In fact, they might've seemed, on first encounter, to be mere ciphers for the prize itself -- for the ideal of democratic internationalism it represents and for its slow gyre from country to country, from literature to literature. Yes; Gao Xingjian, one might've thought. It's just about time for a Chinese author to win. What a hard struggle he must have had with the authorities there, getting his ... er, plays or poems or things published. With V.S. Naipaul, there's no hint of that. In choosing him as this year's laureate for literature, the Nobel committee has allowed the controversial Naipaul's influence -- his aura -- to accrue to the prize as much as the other way around.

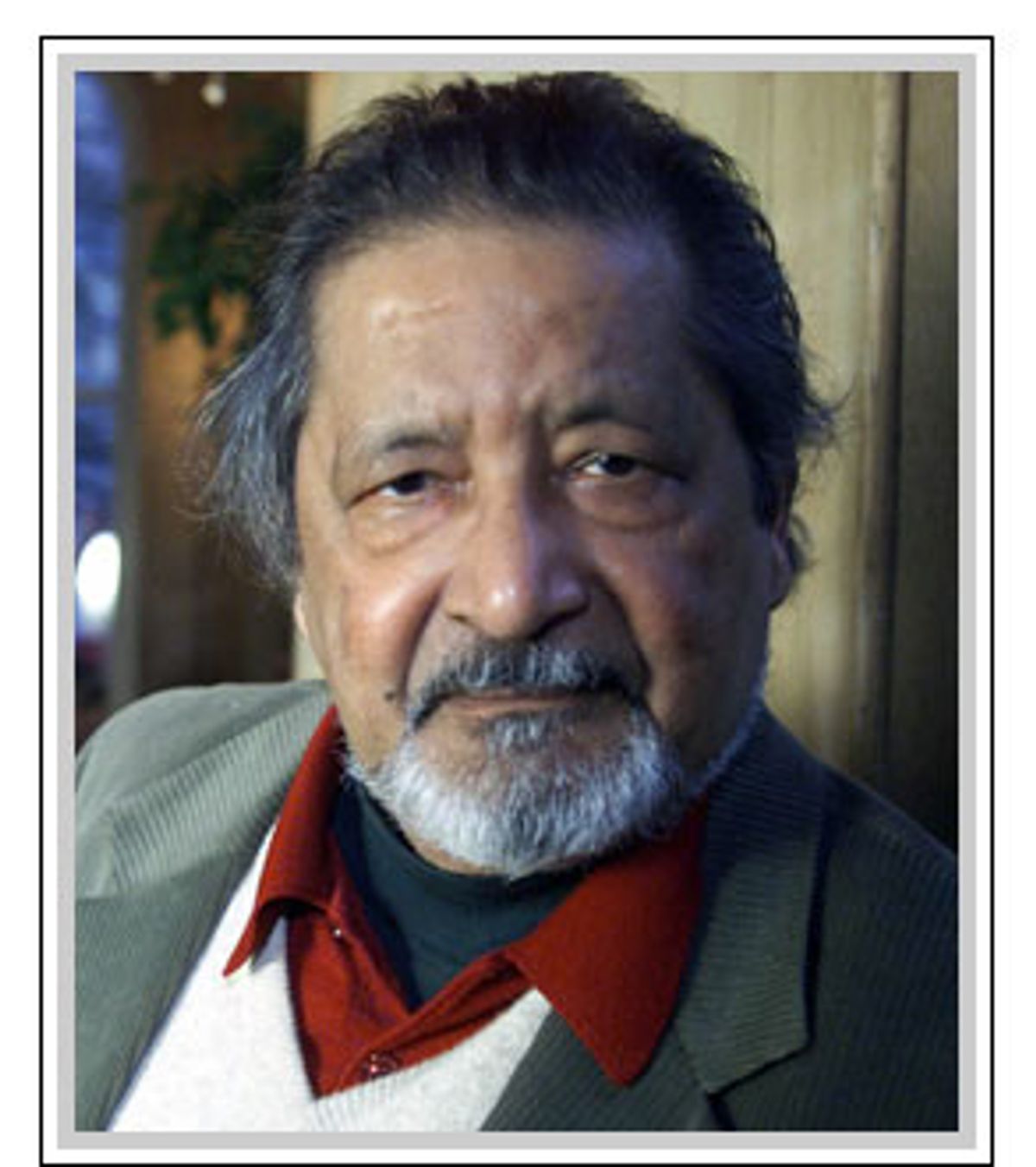

The Trinidadian-born novelist and travel writer -- Indian by extraction, a resident of England by long habit and a weapons-grade grumpus by trade and affinity -- was called "the greatest living writer of English prose" on Friday, in the Indian Express, a distinction for which a pretty good case can be made. Naipaul is claimed by India and by the Caribbean as a native eminence, and is devoutly read wherever literacy in English prevails, as well as in parts of America. His influence is global and undeniably well-founded.

And more saliently, Naipaul is the world's keenest critic of the often dirty, noisy, ill-governed places on the globe where poor, dark-skinned people live: Africa, the Indian subcontinent, the West Indies and so on. He's probably the world's most eloquent champion of Western civilization, British-Empire-style, as a proof against the roil and ferment of the hot countries, of whose residents he writes well and often sympathetically, but who he hasn't hesitated to call, on occasion, "monkeys" and "wogs." According to his fellow West Indian Nobel laureate Derek Walcott, "Naipaul does not like negroes."

But most saliently, Naipaul is a critic of Islam, and especially of its more evangelical, totalizing strains -- calling it, in his 1998 book "Beyond Belief: Excursions Among the Converted Peoples," "the most uncompromising kind of imperialism." The founding of Pakistan, Naipaul believes, was a bad idea that sought to render its citizens as "empty vessels" to their faith. Islam, he says, produces countries and peoples without ties to the past, and with only the crudest notions of the future -- countries with "an element of neurosis and nihilism" that can be "easily set on the boil." At a reading for his new book, "Half a Life," in London last week, Naipaul said that Islam "has had a calamitous effect on converted peoples," and called the history of Pakistan a "terror story."

Others, including the mainstream of Middle East experts, disagree. (Some, like Edward Said, have been set on the boil.) And to be fair, Naipaul has offended nearly everyone at some juncture or another, including Hindus, Trinidadians, Britons (Tony Blair in particular) and fellow writers of every stripe. He recently called E.M. Forster, author of "A Passage to India," an "odious fraud" and a sodomite. A prior feud with former protégé Paul Theroux resulted in "Sir Vidia's Shadow," a book of humor and calumny against Naipaul.

But what makes Naipaul's win this year a rare event, Nobel-wise, is that the prize's tradition of democratic internationalism has now come down explicitly against something, rather than simply for something. The Nobel in literature stands for, as ever, a global community of letters in which all races and nationalities might share. It's for tolerance and the rule of law. The choice of Naipaul can be interpreted as a retort to militant Islam, and the head of the Swedish Academy (the organization that selects the winner), Horace Engdahl, has gone on record as not having a problem with that. But, in choosing Naipaul, the Academy has also struck a blow against any alternative to the idea, now endemic, that the West knows what's best for everyone, and that the rest of the world had better get with the program.

For all that Naipaul despises colonialism and its aftereffects, he's the other laureate most like Rudyard Kipling (Kipling himself won the prize, in 1907). And if their words could be blended in chorus, they might agree as thus: They are our smaller cousins and our charges, these hapless brown devils, these be-turbanned and prayer-droning Orientals. May our Prometheus torch illume them, and may they prosper -- but let them always ask of us, and never demand.

It's a position that had its problems even in Kipling's day. It's, as well, a position to make a Trinidadian Hindu come off like the pitcher of one of those overardent West Indian cricket squads, the kind with the too-white uniforms who are always beating the home teams by playing harder than you're really supposed to.

And so goes the Nobel this year. But for all of this, Naipaul is perhaps the best writer of English prose alive today -- or at least one of a very few who can properly be called magisterial. He's one of the keenest and most incisive observers ever to have written on the Third World, and his travel books, especially, show a depth of spirit and understanding of his subjects, unaffected by race or station, animating both the differences among their cultures and his (and ours), and the commonalities among all people. Naipaul, at depth, is a writer (if not always a private man) with an abiding sense of justice and decency. And although he's given to tartness, and is annoyed past reason by noise, and dust and bad air and crowds and untidiness and late trains and grandiloquent bureaucrats and crummy hotels and all things of that nature that the Third World is built of, his powers of synthesis and analysis are scarcely to be rivaled. Naipaul takes the trouble to know the places and people he writes about, and to know them intimately. And he has created an oeuvre that would, in any year, be a credit to the Nobel rolls.

He was born in 1932 into a Brahman family of literary bent, and went on scholarship from Port of Spain, Trinidad, to Oxford in 1950. He turned freelance after getting his degree, did a stint as a commentator with the BBC and began to write novels. Those from his first period, including 1957's "The Mystic Masseur," the following year's "The Suffrage of Elvira" and "Miguel Street" (a story collection) from 1960, pretty much came and went in the way that pretty good books come and go from year to year.

It was in 1961, with the semiautobiographical "A House for Mr. Biswas," that Naipaul's style sharpened to a point, and his fiction burgeoned into epic tragicomedy. The hapless title character, a Trinidadian Brahman based on Naipaul's father, wants to exempt himself from the bounds of his religion and culture, but passes his life caught in a web of social obligations, bouncing from job to job and vainly striving for a house -- and a place -- of his own. Mr. Biswas' son is a young writer of promise. The novel is, despite its sharp comedy, also a subtle and sensitive generational bildungsroman, with a story familiar to those freighted with their parents' unrealized ambitions, or set free to rise by their parents' efforts.

"Mr. Biswas" is often called Naipaul's fiction masterpiece, while his 11 subsequent novels tend to hew to the author's own self-assessment, from a 1979 interview: "I am the kind of writer that people think other people are reading." "Guerrillas," from 1975, stands out, as does the Booker Prize-winning "In a Free State" (1971) and the Proustian, semiautobiographical "The Enigma of Arrival" (1987). The new "Half a Life," also muted autobiography, was reviewed presciently by Paul Theroux, who said it would lead to "great reviews, poor sales and a literary prize."

Naipaul traveled widely in the 1960s and '70s, beginning his far more influential nonfiction career with such titles as 1962's "The Middle Passage," on his travels in the West Indies, and 1964's "An Area of Darkness," the first of his books on India. "Area of Darkness" and his next on the topic, 1977's "India: A Wounded Civilization," were jeremiads of disaster, impeccably written, in which Naipaul saw India's future ruin in the filth, noise and disorder with which it greeted him.

His 1979 novel "A Bend in the River," 1980's "A Congo Diary" and sections of that year's essay collection, "The Return of Eva Peron," turned the lens on Africa, a continent of "half-made societies that seemed doomed to remain half-made," such as the Zaire of Joseph Mobutu -- a land fraught with "lunacy, despair." Islam first fell under his gaze with 1981's "Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey" and again with 1998's "Beyond Belief" -- like the previous books, masterpieces of reportage haunted by doom and dark prophecy.

1989's "A Turn in the South" visits America below the Mason-Dixon line, a more foreign (if more immediately familiar) culture to Naipaul than even Zaire's, and one in which the author registered as neither white nor black, and could thus write evenhandedly about race, speaking to everyone without piety or pretense. "India: A Million Mutinies Now" returned to the subcontinent, somewhat less bleakly than before, recounting the life stories of ordinary Indians, and concluding that although caste, religion and tradition were coming under challenge and diminishing, "there was in India now what didn't exist 200 years before: a central will, a central intellect, a national idea."

So too, however, with Islam. The only writer in Arabic ever to win the Nobel (in 1988) was Egypt's Naguib Mahfouz, another name the ordinary educated Anglophone wouldn't be expected to have known, and the author of the controversial novel "Children of Gebelawi." Mahfouz immediately became the subject of death threats, and was compared to Salman Rushdie by Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman, the blind cleric thought to be behind the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center, who said that if the novelist did not repent, he would be killed. Mahfouz was stabbed on a Cairo street in 1994 and partially paralyzed.

And while there's no reason to suggest that Naipaul's case is in any way similar (he's a nonpracticing Hindu rather than a Muslim, and while critical of Islam, has never written anything that even a zealot could construe as blasphemy), it's hard to avoid the notion that art and literature are no longer, as they were once thought to be, any more immune from politics in the West than they've been under Islam. Engdahl, commenting on Naipaul's selection, stated that "Literature is the basis of a worldwide community, which is obviously not based on violence or hatred, but which paves the way of mutual understanding between cultures and people." Naipaul, however, has already voiced his support to the war in Afghanistan, and believes, according to yesterday's London Sunday Telegraph, that "the vermin of the Taliban government must be overthrown." At the moment, the laureate isn't sounding much like a champion of "mutual understanding," an oddly reassuring indication that even the literary world's most hallowed honor -- a prize notorious for turning those who win it into cautious, solemn bores -- won't tame him.

Shares