Sometime last spring, at the alt-weekly Philadelphia newspaper where I work, something funny began to happen: Each week, in the lower left-hand corner of the record reviews page, appeared a new item called "Macy Gray Quote of the Week." To the best of my knowledge, there were no meetings of the arts and entertainment staff to institute this new feature; nor was there an e-mail or memo. Instead I assumed that the feature was just a private exchange between the art director and the paper's editor in chief who, we all knew, followed the comings and goings of Macy Gray, wayward pop star and irrepressible nu-soul diva, with an enthusiasm usually only found in UFO aficionados and conspiracy theorists.

The quotes invariably went something like this: "My new album is a sexy mushroom trip with honey halter tops and I'd like to punch Mariah Carey!" They usually sounded completely made up. One day, I finally asked the boss, who indeed was the person responsible for finding the quotes, what was up. He simply shrugged and said, "Well, it's pretty easy to find this stuff. It seems like she says something totally ridiculous every day."

While the above Macy quote is entirely paraphrased -- in fact, it's a composite of a whole slew of totally goofy shit she's come out with in recent months -- the fact remains that few pop stars have had such problems with linguistic coherence as Macy Gray. Her antics in the press have often been high comedy not so very far removed from the work of, say, Jonathan Winters: childlike, disarmingly honest and, as often as not, more than a little sad-eyed. Desperate even.

And among the pop pantheon of Mariahs, Celines and even Fionas -- all entertainers that you could call head cases without risking a libel suit -- even fewer stars have appeared to be more openly at war with themselves than Macy Gray. Forces within her seem to conspire toward implosion at every turn, and it's only because when you get right down to it, Macy Gray contains dippy multitudes.

First, there's the nu-soul diva, an heiress to all the soulful sass and witty melancholia of Billie Holiday; the black Dorothy Parker. Then, there's the hippie superhero, a psilocybin mushroom cloud of free love, sexual self-awareness and libertine licentiousness; an all-encompassing chakra of positive, party-funk-infused vibes. Next, in songs like "Gimmie All Your Lovin' or I Will Kill You," there's the avenging woman, scorned by life and love, mad as hell and not gonna take it anymore; she's like the lady in the Persuaders' "A Thin Line Between Love and Hate," who one day tires of her lover:

I see you in the hospital

Bandaged from foot to head

In a state of shock

Just that much from being dead

You couldn't believe the girl would do something like this

You didn't think the girl had the nerve

But here you are

I guess actions speak louder than words.

There're probably some other archetypes that Macy Gray wrestles with -- sometimes within the space of even just one song -- but these three, really, make up the hat trick that has turned her as often as not into such a compelling mess.

This was not always so. When Macy Gray debuted in 1999, she was simply pitched as a direct emotional descendant of Billie Holiday -- a do-right woman forever doomed to the shitty luck of being saddled with one do-wrong man after another. When you matched that idea up with Gray's boho look of Afro-chic meets Garanimals, it became pretty obvious that Macy Gray was gloriously all by her lonesome in the pop landscape -- perhaps, we thought at the time, here was a real person, a living breathing artist making pop and soul without all the slick, bland MTV crud.

Lots of folks bristled at the claims on Gray as the New Holiday -- I personally always regarded her as the New Carol Channing, whose pipsqueaky, straw-mouthed wisp Gray's voice most comically resembled. But the record that became her calling card, "On How Life Is," had lots more going for it than the list of pop-cultural signifiers it may have invoked, explicitly or otherwise. Anchored by the single "I Try" -- which quickly evolved into a staple on VH-1 -- Gray's genius was to stick her weird little voice into tons of memorable little choruses that simply would not relent until they became pleasant memories.

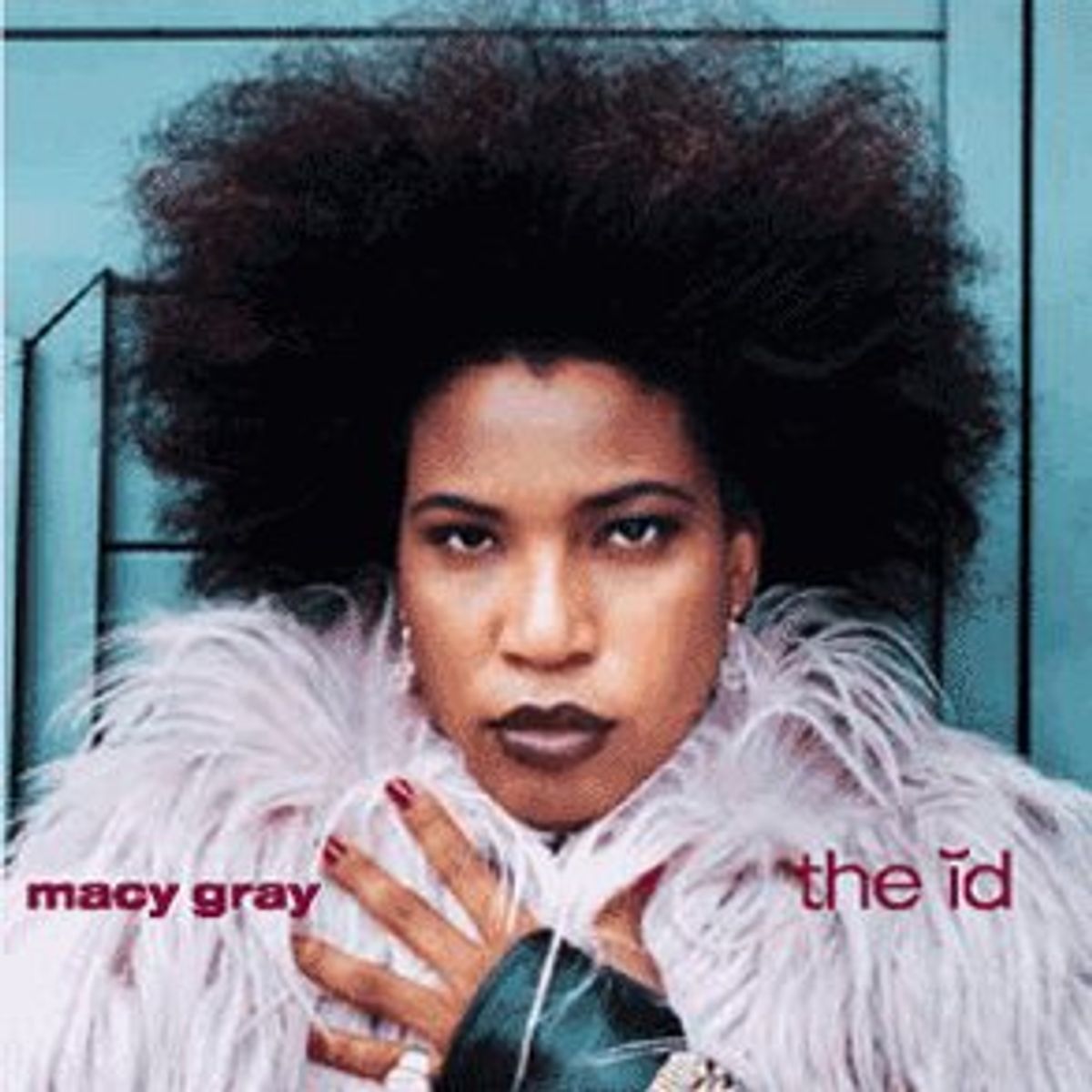

That she was largely able to evolve her persona since then into something else entirely without the aid of any new albums of her own in two years' time is surely some kind of triumph of celebrity, if not sheer personal will. Three years ago, Macy Gray was an unknown; a year after that, she was introduced as the alt-rock generation's Billie Holiday; and sometime between then and the release of her latest album, "The Id," she became a minor icon and beacon of all the disparate clichés of human relations that tell us until we're sick of hearing it that men are from Mars and stoner soul divas are from somewhere else.

This notion that Macy Gray is the consummate sister, doomed in love but brave enough to still demand it, has never sat well with me for the simple reason that something else, something besides the crazy quotes and the silly songs, has always told me that Macy Gray is smarter than this. But the sentiment persists throughout "The Id," and it's exactly why the record is, almost from note one, doomed itself. Gray is so tied up into her own psychosexual impulses -- which she imagines are completely new and specific to her -- that a lot of "The Id" feels like pandering. To what? To whom? Well, to the notion itself, and also to the only demographic naive enough to embrace its supposed, common-sense, "Chicken Soup for the Soul" truth: teenage girls.

Gray furthers the whole swinging-with-two-bats thing by caging all this hammy sentiment in a style of smart pop melody that's so rooted in '60s pop -- the intro of "Sexual Revolution" even dials up budget Beatles before hiccupping straight into roller-disco -- that whole chunks of "The Id" feel oddly rockist. Even when she's got Ahmir "?uestlove" Thompson of the Roots laying down beats, Gray is always a lot closer to Steve Miller than Slick Rick -- even when Rick himself guests on "Hey Young World Part 2." (In fact, there's a part here when she peeps "wooopeedoo" in such a way that you would have sworn that someone just called her the Gangster of Love.)

Rockist notions aside, though, so much of "The Id" seems of a whole with "Our Bodies, Our Selves" and any other number of pop-psychology/sexuality touchstones that, as a boy, it feels unwelcoming. As a man -- and beyond that, as simply a thinking person -- it feels patently misleading. When Gray sings about her sexual revolution, what a freak she is and how she wants to be the butter on some guy's bread in "Sexual Revolution," "Freak Like Me" and "Relating to a Psychopath," she might possibly be kicking a few frigid Mormons out of her Girl Gone Wild club. And there's nothing wrong with a little sexual rebellion to stir up the soccer moms.

But what's infuriating about all of those statements, all that freaky posturing, is that they're not even true. Because the Macy Gray on "The Id" is about as freaky as milk. So Gray likes guys who don't like her back. And apparently she also likes to smoke pot and masturbate. None of that makes her a freak. Perhaps a renegade Tri-Delt mastering the art of the puritanical blush, but a freak? Hells no.

The sad part of all this is that Macy Gray is a freak. Like Rock Hudson playing a straight man playing a gay man in "Pillow Talk," Macy Gray on "The Id" aims to get to the bottom of her soul, but backs off when she realizes what an abyss of raw emotion she might find down there. The decision seems like it's done for the audience's benefit as much as her own.

And that's her crucial mistake -- and unfortunately, probably the one she'll keep making -- because, in the end, "The Id" is really not much more than the "psycho bitch" rhetoric ladies like Macy have probably heard too much of already. It's not disingenuous -- it's downright defeating. And something in Macy's voice, in that phrasing, in that outsider, bedroom rasp tells me over and over that she knows better.

Throughout her brief career, Macy Gray has been accused of being a novelty singer, to be filed away in a wax museum of strong weird personalities from Tiny Tim on up to Screamin' Jay Hawkins. That's close, but it doesn't really do a great job of pointing out what's different about Macy Gray, and how, if things work out the way they're supposed to, she'll surpass that novelty and go on to make record after listenable record. As it stands now, she's one of the few humorists in American popular song that we have, intentional or not. And in any case, she's certainly the first soul singer in a long time who's had the guts to laugh at herself. Now, if we could only get her to stop.

Shares