I’m not the type to love a place just because I happened to have been born there, but I’ve always wanted, at the very least, to respect America, and mostly I have. If our nation hasn’t always lived up to the ideals it trumpets, I believe that we get closer every year because the majority of us are committed to making this experiment work. What I’ve never questioned is America’s know-how, resilience and fortitude — our gumption — even when I’ve had my doubts about how we use it.

That is, I hadn’t questioned our gumption, until about two weeks ago.

In the days following the body blow of Sept. 11, my faith in our nation’s ability to behave with grace under pressure seemed to be borne out. It wasn’t just the firefighters and police officers; it was the volunteer rescue workers, the people standing in line for four hours to give blood at the hospital on my block, the citizens from other states who got in their cars and drove day and night to reach us here in New York so they could offer their help in any way. The corresponding slogans — “United We Stand,” etc. — were cheesy, but they didn’t seem outright delusional.

All it took to explode that dream were a couple dozen contaminated letters. Now, doctors are besieged with requests for Cipro prescriptions by patients who have no reason to think they’ve been exposed to anthrax. The government is planning to blow a huge chunk of the public health budget on this probably unnecessary drug. The House of Representatives closed up shop in a paroxysm of what the media politely called “jitters” — the New York Post was alone in calling them “wimps” — after Senate majority leader Tom Daschle’s office received an anthrax-laced letter.

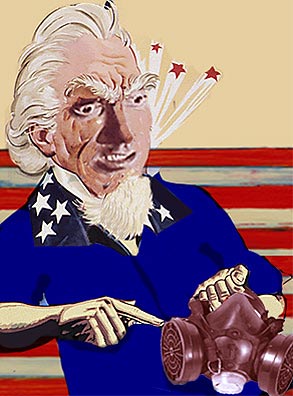

Columnists like the New York Times’ Maureen Dowd and the Washington Post’s Sally Quinn write of frenzy among the chattering classes (make that the teeth-chattering classes), leading to runs on gas masks, canned goods and of course, more Cipro. Paranoid Americans who think they’ve been exposed to bioterror are threatening to cripple the healthcare infrastructure that would be our first line of defense in the event of a serious attack. The thin, high whine of panic is in the air.

It’s worth reiterating right now that exactly one person — the first person diagnosed, before we even realized his infection was intentional — has died of anthrax so far. A mere seven more have contracted the illness, and all are expected to make a full recovery. The remainder of people who “tested positive for exposure” aren’t even sick and don’t amount to more than 40 victims. Salmonella has probably killed more people in the past two weeks than anthrax has, and I’m sure that more have died in automobile accidents. So why don’t we all stop eating, and resolve to walk everywhere we go?

It’s depressing and demoralizing to see a nation that two weeks ago was congratulating itself on its “unity” dissolve into a collection of gibbering hypochondriacs. On the big screen of our collective imagination, in that movie where a handful of mismatched strangers is trapped in an imperiled high rise or ocean liner or spaceship, we Americans want to believe that we’re the Bruce Willis character, the coolheaded, competent, wisecracking, fast-thinking man with a plan. In reality, we’re the incoherently screaming lady who has to be slapped until she comes to her senses — and even then turns out to be little more than dead weight.

Oh, and by the way, there’s a war on, a tricky, demanding conflict with the potential to set off a worldwide cross-cultural military conflagration. That merits a bit of our attention, I’d say. Yet stories about it are being driven off the front page by articles in which public officials and so-called experts make vague, inflammatory statements about the anthrax menace that later have to be semi-retracted or otherwise qualified by other officials and experts and unnamed sources. (Just what is “weapons grade” anthrax and exactly how sophisticated does a lab have to be to produce the powder that failed to gravely afflict anyone in Daschle’s office? Your guess is as good as mine.)

Of course there is a real danger, even if it’s a small one, and it’s true that we can’t predict where this not very lethal terrorism will hit next. People need to take some precautions, to be observant. But the quality that’s called for is prudence, not hysteria, which is the flip side of the empty, ignorant bluster other Americans have indulged in since Sept. 11. In a perverse way, Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaida paid us the compliment of believing that it would take coordinated, massive attacks and hideous carnage to shake America to the core. Yes, bin Laden called us “soft” for pulling out of Somalia after losing only 18 soldiers in the disastrous 1993 raid on Mogadishu, but little did he realize how spineless we really are. Mohammed Atta and company might have saved themselves a lot of trouble by staying safe and snug in a Florida suburb, and just firing off a couple of tainted letters every week.

The genius of targeting the media — no shortage of high-strung neurotics there — is a testimony to the perpetrators’ savvy. Yet I can’t help but think that postal terrorism lacks the flourish, the opportunity for glorious martyrdom typical of the mujahedin. We still don’t know who’s responsible for the anthrax scare, but in my darkest hours, I wonder if the sneaky, craven tactic of sending poisoned anonymous letters mostly to celebrities isn’t in its own way quintessentially American.

It’s especially painful now to think of the way the British behaved during the Blitz, when they were subjected to the kind of punishing bombardment that Americans have dished out but never actually taken. They huddled in cellars with candles, singing songs together, and when the bombs stopped falling, they dusted themselves off, changed their clothes and went out to the theater.

To be fair to the public, the government has utterly fallen down on the job for the past two weeks, doling out announcements that range from unconvincingly blithe reassurances to scary tidbits that resemble nothing so much as the rumors passed around on elementary school playgrounds. Without leaders who demonstrate a responsible, adult response to the domestic situation, people who are so inclined have been encouraged to run around like chickens with their heads cut off.

It’s not just that the Bush administration has been logistically unprepared for this sort of crisis, it’s that they’re conceptually unprepared. Here in New York, as Michael Bloomberg launches into the last leg of his mayoral campaign, pointing to his success as a businessman as proof of his qualifications, what I keep thinking is, “Yeah, but New York is a city, not a corporation.” We need a mayor, a civic leader, not a CEO. Likewise, the Bush administration approaches governance as if it were the equivalent of running a big company, with no instinct for the skills of reassurance, motivation and inspiration that leadership through dark times requires.

I’d like to believe that Americans want to be brave, want to pitch in, want to find a meaningful way to respond to this crisis, this titanic shift in our perceived role in the world. We’ve just forgotten how. Maybe when our leaders can’t come up with a better recommendation than “Go shopping,” when their vision of citizenship is so impoverished that consumerism is how they suggest we exercise it, it’s not that surprising that our civic culture degenerates into every-man-for-himself drug hoarding.

But America’s government is more than a service provider, and all of us are citizens, not customers or clients. The current crisis is about more than just the fear of disease and hijackers and car bombs; it’s about remembering what, beyond mutual self-interest, holds us together, what it feels like to care about something bigger than ourselves. We sure could use some help getting back to where we once belonged.