Cancer does terrible things to people, but what it does to movies is pretty awful, too -- particularly when you consider that cancer movies are a purely man-made phenomenon. How long before we get a cure?

Irwin Winkler's uplifting weepie "Life as a House" is life-affirming in a by-the-numbers way: Kevin Kline, a vaguely eccentric, aggressively unsuccessful architectural model builder, becomes terminally ill. His son, Hayden Christensen, a sullen teen given to facial piercings and glue sniffing, lives with Kline's ex-wife, Kristin Scott Thomas. Kline scoops up Christensen and forces him to live with him over summer vacation, helping him knock down the old shack he's been living in and build his dream house before the Man Upstairs flips the power breaker off for good.

If you've been itching to embroider a sampler but find you're just plumb out of slogans, "Life as a House" (directed from a script by Mark Andrus, who co-wrote "As Good as It Gets") might be a good resource. There's Kline's line, spoken in voice-over: "I always thought of myself as a house ..." (Just not quite as big, I thought to myself, though Kline's rumination is somewhat more profound.) The movie's themes alone practically scream out in cross-stitch. Consider "The family that works together stays together," or "Don't let your dreams die with you," or "If you had parents like these, you'd sniff glue, too."

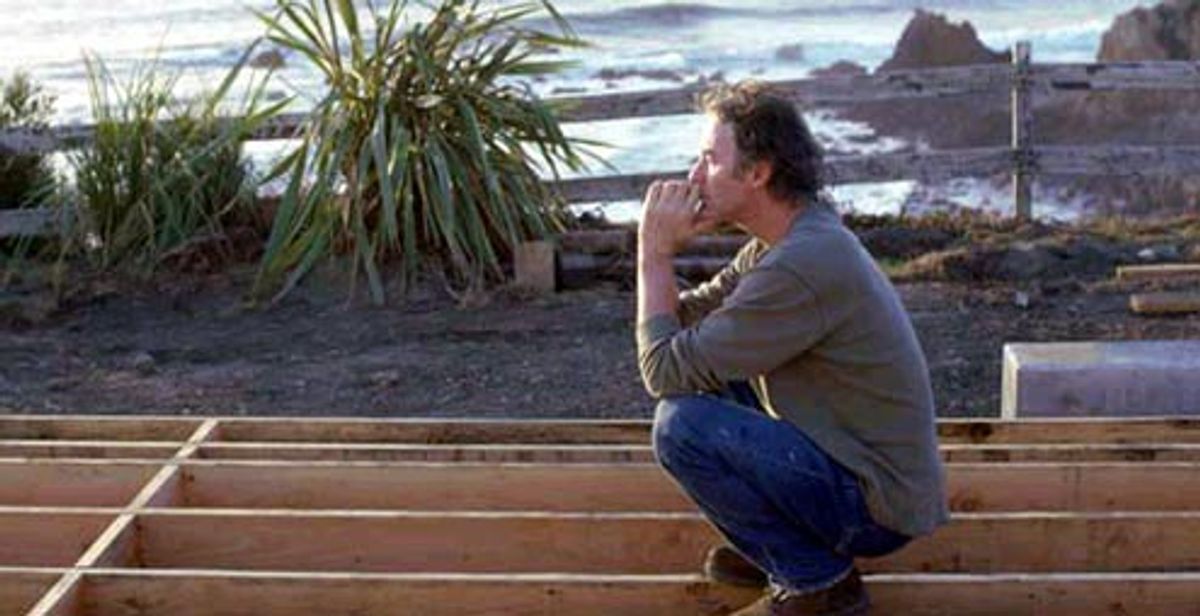

OK, maybe not that last one, but you get the idea. Set on a gorgeous stretch of California coastline and shot by Vilmos Zsigmond, "Life as a House" sure looks pretty. But it seems to go on forever, partly because Winkler makes every conventional choice in the book. There's a scene where Kline and Christensen, still at odds with each other, demolish the last bits of Kline's old shack, whacking away at its wretched beams with sledgehammers. The way the scene is shot, you understand how cathartic it must be to bust down an old house you always hated anyway, and you also get a sense of how swinging those hammers would probably be a much-needed release for an estranged, frustrated father and son. But Winkler sets the scene against a dorky stretch of music (the movie was scored by Mark Isham), as if he were fully aware of its potential power and sought to soften it. He ends up completely deflating it.

It doesn't help that the movie's shorthand is numbingly conventional. We know Christensen is coming around and turning into a nice boy when he stops wearing eye makeup and trades his New Wave-style fitted T-shirts for baggy plaid numbers. (He actually looked rather quaint as a glam-punk, and somewhat retro-original, but we all know that good, reliable American boys wear Abercrombie & Fitch.) And when his parents, who used to feud constantly but have slowly come to look more kindly on one another, slow-dance to a tape of "Both Sides Now," you marvel that a bit of glue and a little weed was ever enough to dull his pain.

Kline is a superb actor, and he's aging beautifully: Who wants to see him playing Camille when he's got so much life in him? (He should be strutting much jazzier stuff, as he did in "In & Out" and "I Love You to Death.") In "Life as a House," as his cancer progresses, he starts to look more and more like Steven Spielberg on a bad day, all frizzled and grizzly. He has a knack for breathing life into even the flattest lines, but why should he have to?

And Kristin Scott Thomas doesn't need any more crisp, wifely roles, even if she's allowed to soften up by the end, as she is here. She knows how to turn her cool, almost cold beauty back on itself, warming it up into something flirtatious and inviting. (She won me over forever in "Under the Cherry Moon," as she attempted, under Prince's tutelage, the proper enunciation of "wrecka stow.") Thomas is adequate here, but she seems tamped down by the material. For a movie that's all about embracing life wholeheartedly, "Life as a House" sure does a good job of keeping its actors in check.

But then, even though cancer movies are ostensibly about milking those last precious moments of life, there's almost always something a little scolding about them. We're supposed to tumble out of the theater, being grateful for what we have, ready to hug a child or a big dog. Some of us, though, are simply grateful to leave the theater. That's the moment when we truly know that life is good.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

If you liked this feature, please take a minute to click here to read a note from the Arts & Entertainment staff about Salon Premium.

Shares