Thabasum Mufti sits in her tidy sitting room in a middle-class neighborhood and pulls out a neatly folded jersey velvet fabric in rich red and black colors from a black leather suitcase labeled "Carlton International." A tag is stuck into the green velvet fabric with a straight pin: "1,000 rupees" ($15.87).

With her collection of fancy fabrics for sale, Mufti is a sitting-room soldier in the cause to raise rupees for the mujahedin fighting in Afghanistan. Beside her is another suitcase filled with fabric, donated by a friend from her "jahaze," a trousseau of sorts meant to keep a new bride in high fashion for many days.

It's a picture-perfect middle-class home. On a sofa nearby, one of her two children, Anum, has left behind a copy of the children's book series "Goosebumps." Visiting women feel the cotton of a black fabric with big white polka dots ("2 single bed sheets, 200 rupees"), a shocking pink fabric with little flowers ("suit piece, 200 rupees"), a green fabric with shocking pink flowers ("suit piece, 200 rupees") and a fuchsia fabric ("suit piece, 200 rupees"). Mufti's young son, Mustafa, pulls out a CD from his collection to sell for the mujahid cause.

Housewives and grandmothers as well as doctors and women of the educated urban elite are becoming soldiers of the jihad from their sitting rooms, as living rooms are called here, using prayer and tag sales in their artillery of weapons. They consider themselves each a mujahida, the female version of a mujahid, a freedom fighter, part of an Islamic revival over the last 15 years that has even converted thoroughly modern women -- women who used to flash bright shades of Revlon lipstick, their slick, highlighted hair flowing over their shoulders, chic hand-embroidered shalwar kameez suits with sleeveless kurtas (risqui in Islam, which requires women to cover their arms down to their wrists with long sleeves)To be modern was to be called "Mod Squad."

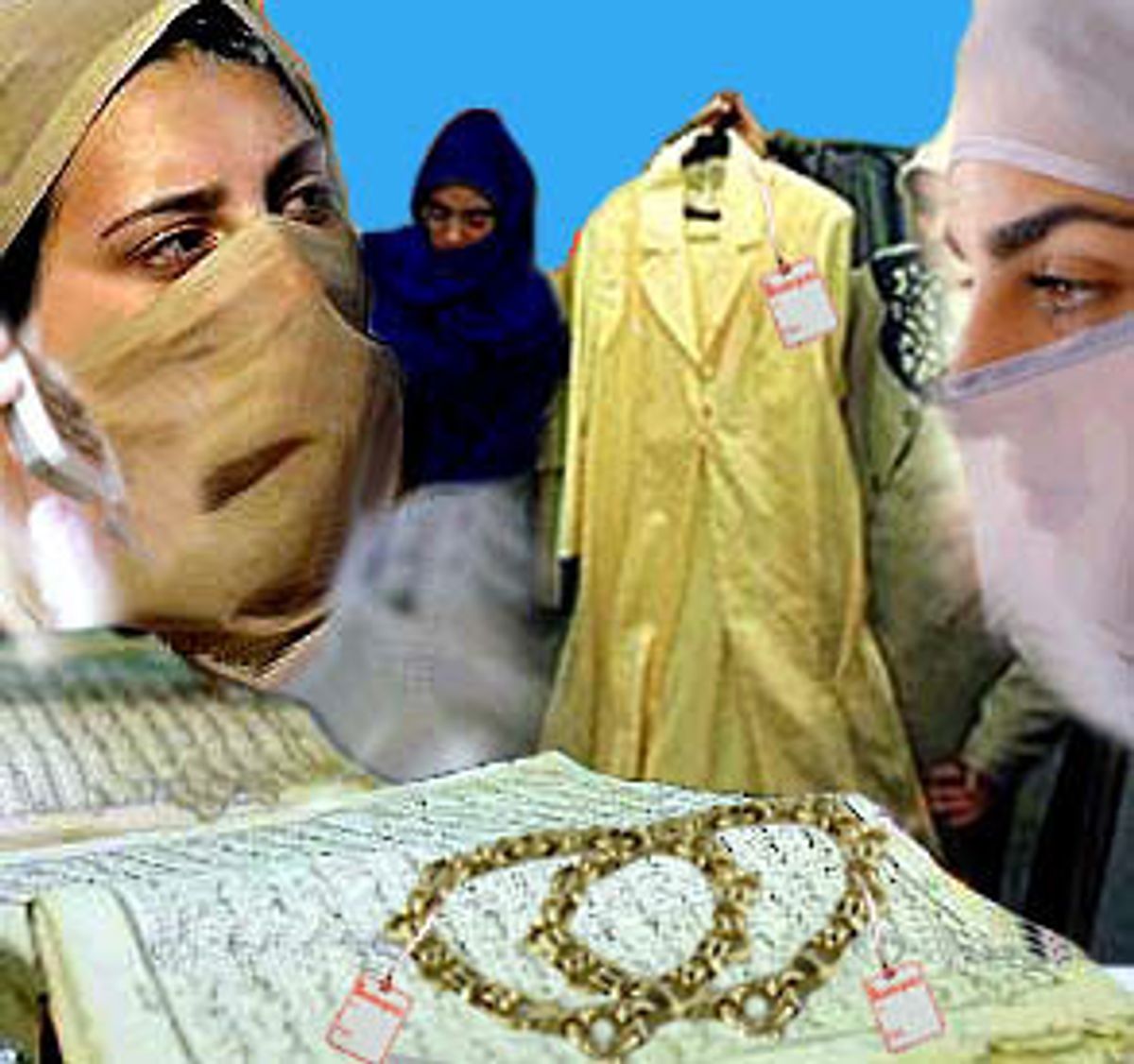

To fight in a jihad, these women believe, doesn't mean simply running to the front lines with submachine guns and anti-artillery weapons. That's a specific type of jihad, jihad bil qital, fighting with actual combat. Strictly speaking, jihad means "a struggle for Islam" and can be waged on many fronts. The mujahida here is part of a battalion of women quietly maneuvering around town in shapeless navy gowns, headscarves tightly pinned at their chins and, often, partial veils (niqab) drawn up over the bridge of their nose as their battle armor. They wield Nokia mobile handsets while driving mostly shiny white Honda Preludes through the quiet streets of Islamabad's F and G sectors, the middle-class through upper-class neighborhoods where they live with servants, microwaves and Paknet Internet connections. And in their own way, they definitely feel they are waging their own unique jihad.

Some take the gold bangles off their arms to donate to the cause, a jihad bil mal, with money, using wealth to fund the fight, they believe, for the cause of Islam. And, like the American women who rallied behind the soldiers during World War II, donating their silk stockings to the armed forces to make parachutes, these women see their activities as simply the ordinary, obvious way to support the war effort.

To them, the U.S.-led coalition attacks on Afghanistan is truly an attack on Islam, and these fundamentalist Pakistani cricket moms' sympathies lie mostly with the Taliban and even Osama bin Laden.

These mujahida come from the generations of women from their 20s through their 60s who have rediscovered Islam. In "Clash of Civilizations," a much quoted book here in these times, author Samuel Huntington chronicles the "Islamic Resurgence" in countries from Algeria to Afghanistan over the last three decades. Students and intellectuals made up the militant "shock troops," he says, but urban middle class people composed the bulk of the movement. Here in Pakistan, that includes the housewife mujahida.

From her sitting room in a cozy Islamabad neighborhood, with wide gates that swing open into driveways, Amira Ahsaan, a veteran political leader, has a special vantage point from which to observe this activity. A mother of four children, she chose not to work after earning her master's degree in biology from Qaid-e-azam University, studied Western society during several years living in New York and now spearheads education about Islam among women. She watches the jihad work now being done by housewives and women professionals and says it's modeled after the historical story of Hazrat Khansa, a mother and poet at the time of the Prophet Mohammed, who urged her four boys to fight for Islam in jihad. She extolled them: "Go into the midst of the thickest of the battle, encounter the boldest enemy and if necessary embrace martyrdom." They died "shaheeds," martyrs.

"Our maternal expression is for Islam. It's not just for men. This is our special role in jihad," she says. "In Islam, women are not prophets. They are the mothers of prophets. This is the role of women. She prepares men for jihad. She is not Jesus. She is Mary." The hadiths, the sayings of the Prophet Mohammed and a guide for Muslims, she says, assigns the reward of jihad to a mother from conception to weaning. She is considered a ribat, one who guards the frontier of Islam. A woman who dies in childbirth gets the reward of a shaheed, a martyr.

Here, men who reach a certain religious discipline are called "mullahs." These women are sometimes called "mullanis," though there really isn't such a thing. They're also sometimes called "chaddar laynay wallee," those who wear a chaddar, yards of usually cotton fabric under which they cloak their heads and bodies to remain modest, as the Quran tells both men and women to be. They glide across town here, gathering in sitting rooms and bedrooms for durs, Quran study groups, sometimes eating dates afterwards. (Many Muslims have traditionally mostly read the Quran in its original Arabic without translations; durs meetings include thurjomah, translations). These women don't give themselves any clever name. They simply call themselves "Muslims." Like Christianity's born-again Christians, these women are something like reborn Muslims.

I have seen something of this evolution in the women of my own family. When one of my sister cousins started becoming a more observant Muslim, my Islamabad phuppi, my father's sister, at first discouraged her. Islamabad phuppi also discouraged a neighbor, Aunty Sultan, from allowing her daughter to cover herself with her dupatta. She was still unwed; covering herself up would make it too difficult to attract a proposal (The daughter got married anyway).

But about three years ago, my Islamabad Phuppi started changing, too, slipping into durs sessions held in the sitting rooms of neighbors. Now, she quietly regrets encouraging one of her daughters to enter a professional field where she works with men.

Another phuppi rediscovered Islam through an Islamic educational organization aimed at women, Al-Huda International, the hub of Muslim rebirths over the last decade. I always felt a special kinship with this phuppi because I look so much like her, down to the mole on our necks, between our clavicle bones. She was always modern, gregarious and "smart," as they like to say here about a well-dressed woman with style. But Islamabad phuppi also discouraged her, arguing, "Your husband won't like it." Still, she moved forward, not hosting the festive mehndi ceremony -- in which the bride has henna ornately drawn onto her hands and feet -- when her eldest son was married, and not allowing mixed gender seating at the wedding. (My wedding in 1992 was the last family wedding to have my younger sister cousins dancing at the mehndi ceremony.)

And at a cousin's wedding not long ago, my smart phuppi's older brother, my bure abu in Lahore, didn't even recognize her when he saw her sitting in full hijab, the flap of a partial veil across the bridge of her nose, so only her eyes were visible. "Assalamalaikum," he said to her, respectfully, as if she was a stranger to him.

Indeed, the return to conservative Islam in Pakistan isn't only coming from men, says political activist Ahsaan. "It's not a matter of a male-dominated society. We have women struggling with their husbands for their right to cover themselves up. It is not a symbol of male chauvinism. We are seeing women who do purdah and hijab" staying primarily at home, and remaining covered up, from head to toe, when they go out "by choice."

Why? It reserves the sanctity of a woman's sexuality for only her bedroom, not for a colleague with whom she might flirt with the flick of her hair. Ahsaan knows the argument that the women of Afghanistan don't have a choice under edicts by the Taliban that they must cover up. It doesn't much disturb her. For one thing, she says, it is part of the culture for the majority, anyway. Two, she says, Afghanistan was a culture of terror and exploitation for women before the Taliban took over. Covering up, she says, brought a safety and security to women that they are entitled to as a right in Islam.

"In Islam, we are given all the confidence of being a woman. We are proud to be women. We're absolutely feminine. We're proud of being feminine. In Islam, a woman is too precious to be shown around," she says. "It's the beautiful mansions that are guarded. A poor man's hut has no door and nothing to guard it. In the West a girl loses her virginity at such a young age. She is like a poor man's hut. Anyone can walk in any time of the day or night. She has nothing to lose."

For the most part, these women are sympathetic to the Taliban, believing that they cleaned up the country's chaos of rapes, robberies and kidnappings following the Soviet pullout from Kabul. They are annoyed by the constant rebroadcasts on CNN of "Beneath the Veil," the documentary that lays out allegations of human rights abuses against the Taliban, particularly women. They claim it is unbalanced footage shot by Afghan Muslim women who belong to an urban elite minority -- women who lack a connection to most of Afghanistan's traditional rural majority.

At Karokoram Apartments, a luxury apartment complex here, about 30 of these bourgeois mujahida gather one recent morning for durs. One, a lecturer in chemistry at a women's college here, leads them through a dua, a prayer, at this time of war. She learned it one recent afternoon when she sat with her daughter in a class at Colours of Islam, a Sunday school of sorts on Jumma, Friday, the Muslim holy day. In class, Madam, as teachers are called here, stuck several paper soldiers into a tray of soil. They were Muslim. Facing them were many more enemy soldiers.

This was the Battle of Bad'r, described in the eighth sura of the Quran, in which pagan tribes launch a war against a ragtag Muslim army with only three camels and hungry soldiers. Madam sprinkled water upon the soil and explained to the children, listening eagerly: Allah answered the prayers of Muslims and hurled rain upon the enemy, making them fall over each other in the mud. The history books say Prophet Mohammed's army won in Islam's first important battle, transforming it from a religion to a state-religion.

The children repeat the dua that the Prophet Mohammed is said to have recited during the war, following Madam's lead: Oh, Allah, protect us from our enemy's plans and misdeeds.

The prayers of many of these women include asking Allah to lead all people, Muslims and non-Muslims, on "the straight path." There is another dua, "Qunoot-e-Nazala," recited recently in a durs, the women holding their open palms before them. It's repeated in other homes and during private prayers said as women prostrate themselves before Allah on the janamaz, prayer rug, they lay out in a corner of their bedroom. It has a more ominous message. It can alienate someone from the West. It frightens me. "Dua for invoking a curse," reads the translation of this prayer.

Prophet Mohammed is said to have recited this prayer after he sent 70 learned men to teach Islam to a tribe of non-Muslims. The non-Muslims, it's said, slaughtered 69 of the learned men, with only one escaping to relate the story. It begins, as do many a dua in times of calamity, seeking forgiveness for Muslims' transgressions, and it asks for Muslims to clear their hearts and join together. "O Allah! Forgive us and all believing men and women and all Muslim men and women and put off actions between their hearts and reconcile between them and help them against your enemies and their enemies."

Then, "O Allah! Curse the disbelievers, those who stop from your way and belie your messengers and fight your friends. O Allah! Put differences between them and make them falter in their footsteps and send upon them your punishment, one that you would not turn away from a transgressing and criminal people."

The "silent majority" Pakistan's president Gen. Pervez Musharraf talks about includes these housewife mujahedin praying this "Dua for invoking a curse." To them, the West is the source of the "criminal people" who are raining death on Afghan civilians, and sending hungry Afghans with hollowed cheeks rushing across the border into Pakistan to flee the war. There is also a Salvation Army effort of sorts that women are spearheading. The night the bombing of Afghanistan began, I went into the house of former Pakistani intelligence officer Khalid Khawaja, a friend of Osama bin Laden and the Taliban. Now, there's no room to sit on the ornately carved upholstered sofa in the sitting room. It's filled with bags of used clothes, sweaters, frocks (as girls' dresses are called here), pillows and a red-checkered baby sleeping bag. They are the donations of two women who dropped them off for distribution in Afghanistan. Winter is setting in; people there will be cold.

This groundswell is coming from an elite crowd: A first-class PIA (Pakistan International Airlines) baggage tag dangles on the handle of a Skyflite garment bag packed with donations. Inside is a flannel pajama suit with a pink rabbit on the front, a frilly pink frock. "It is our 'farz,'" our duty, "to help," says Khawaja's wife, Shamama.

Back in the Mufti house, a daughter pulled out a lime green shalwar kameez suit with sleeves made of a tissue fabric with gold sequins, sitharo ke kam, star work, good for wearing at weddings. One of the household servants, 11-year-old Nazia, plucks the outfit to buy for herself, at a steal, 50 rupees (79 cents). She looks eagerly at a fuchsia outfit with a brocade work kameez. Why does she want her money to go to mujahedin?

"They are Muslim like me," she says.

Another night, 10-year-old Farzeen Tariq, a gregarious, articulate aspiring journalist (if she doesn't become a banker), negotiates 30 rupees (47 cents) for one of Mustafa's CDs, "Read With Me Games." "I'm so happy the money is going for the mujahid," Farzeen says later, beaming with twinkling eyes. "They will have support from me." Last night, young Farzeen saw the Afghan man who sells French fries in F/10 Markaz (market) crying. She overheard why: The man's daughter had died in Kabul as a result of the bombing. "I feel so depressed," says Farzeen.

One morning recently, about 100 women gather in a two-story house off a neat lane. They wear head scarves and sit cross-legged as they listen to a woman guiding them through a translation of a Quranic surah. Inside a small room off to the side, about a dozen organizers of this Islamic educational organization sit on the floor, listening to a woman cross-legged above them. They are impassioned, like others, about the U.S. decision to bomb Afghanistan without first showing clear proof that bin Laden is behind the Sept. 11 attacks. They too pray the duas against the enemy in time of war.

Among them is Bushra Najib, a doctor in her 30s. She chose to stay at home to raise her children and live in purdah, covering her face with a partial veil and gown when she glides around town doing her work as a nazima, organizer, spreading the teachings of Islam. Tooling around Islamabad, talking into her mobile phone to check the address of her next appointment, she talks about her rebirth.

She went to Mecca for haj, the holy pilgrimage of Islam, about six years ago. It's said that Allah will fulfill any sincere prayer said when a Muslim first sets eyes on the Kaa'ba "sharif," the all-black place that's considered the house of Allah. At that time, Bushra said, "Dear God, set me on the straight path."

She started going to durs when she returned home and is now an organizer of this women's movement.

It's a woman known as "Dr. Farhat" who has gotten many educated women to cover up by choice. She is Dr. Farhat Naseem Hashmi, 43, a Quran scholar who started the non-political foundation called Al-Huda International Welfare Organization in 1994, not long after she earned a Ph.D. in Islamic studies from the University of Glasgow, Scotland. She specialized in "Hadith Sciences," a study of how the Prophet Mohammed said pious Muslims should live their lives. Her Web site biography mentions her "learned husband" and Al-Huda as "their brainchild."

From its headquarters in a sweeping house in the upper class neighborhood known as F8, the organization runs one-year diploma programs, summer "crash courses" and regular programs such as a recent discussion of "The Muslim Marriage Guide," a provocative book by Ruqaiyyah Waris Maqsood that lays out a Muslim wife's rights in a marriage, including the right to "imta," fulfillment in the bedroom. With the support of its well-to-do students and, they would say, Allah's blessings, the house is now under construction with upgrades and freshly applied new concrete. A Nissan Sunny with a Karachi license plate sits outside with a Rutgers University bumper sticker on the back window and another sticker above it: "Smile! Allah Loves You!"

Inside the office, a large room cordoned off with a couple of desks and a sitting area, a binder sits on a shelf with "THINGS DONE" printed on the side in English. A young woman in a black gown and blue-gray scarf taps names and numbers into a spreadsheet. Another young woman whispers to one of the senior officials that a man is coming in to fix the photocopier. The women pull their veils over the bridges of their noses, as the photocopier man tinkers with the machine, his back to them. This is a touchy time. They want it to be known that they aren't a political organization. Simply educational and charitable.

In the organization's first year, they had 47 graduates from their one-year program. Last year, they had about 200 graduates. This year, they expect about 300 graduates. That doesn't include the thousands of women who spill into its regular classes and durs gatherings. There is a tension: One Islamabad psychiatrist calls this revival the "al-Huda terror," because he sees teenaged girls as patients, in conflict with reborn mothers over such things as mothers wanting to pull them out of the private coed schools they've been attending for years and enroll them in government girls' schools.

Pakistanis are well aware of this revival movement. Last December, during the holy month of Ramadan, the national English-language newspaper Dawn reported the popularity of "Fehme-Quran" classes taught by Al-Huda's Dr. Hashmi among "the beautiful begums," married women.

"There are the usual ... beautiful begums, dressed to kill, who fumble with their dupattas for the umpteenth time in an attempt to cover themselves, while sitting on these amazingly comfortable folding black chairs, a Quran clutched close to their hearts. Even their walk is a pace faster, one notices, than the one at the 'aunty park,' lest they miss out any discourse." ("Aunty park" refers to parks where women and men walk after the morning's fajr namaz prayers, the sun just rising, their lips often moving as they silently recite words that are part of "zikr," the remembrance of God, their fingers moving the beads on a "thuzbi," a Muslim's rosary beads.)

Dawn also points out: "You'll find the middle and lower middle class women, too, disembarking from rickshaws and cabs, seeming every bit as enthusiastic as their more modern counterparts alighting from Civics and Corollas."

My Islamabad phuppi is with me as I visit Thabasum Mufti, the mujahida raising money in her sitting room, whose son is selling his CDs. A while back, I know, Mufti was wearing sleeveless kurtas, praying irregularly, often only on Friday. Then a friend invited her to durs led by Dr. Hashmi. At the time, Mufti admits: "I didn't go for 'ilm,' knowledge. I just didn't want my friend to be mad at me. I thought I'd go late and leave early." She sat right in front of Dr. Hashmi, thinking she could outsmart her teachings. Dr. Hashmi started reading from the Quran: "We were born only from one person." The lesson was to love others because of a devotion to God, not in exchange for love received or expectation.

"This was the first day that I loved God," Mufti says now.

She started studying the translation of the Quran. Four years ago, she started making the rounds more regularly at durs gatherings. Two years ago, she took the al-Huda year-long course. She started living her life differently, pulling her veil up over her nose when she readied to go outside, putting new importance on Jumma (Friday) as a special day when she changes the bed sheets and puts daal (lentils) and masala (spices) in bottles. Now, she sweeps into houses to teach the translation of the Quran.

"Now, my life has begun," she says.

During this past Saturday afternoon's durs, Mufti sits on an upholstered chair and reads from a thick Quran with words highlighted in pink, blue, yellow and green, writing in the margins. She wears a white dupatta that frames her face snugly, spreading over her shoulders with a pattern of white tulips and a tan-colored pin under her chin. Today's topic: the Quranic teachings about women's rights in a separation or divorce. She lays out the long process of separation, mediation and reconciliation required before a couple can get divorced.

My phuppi asks the question on the tip of anyone's tongue when they discuss the issue of women's rights in Islam: What about "Thalak. Thalak. Thalak." That a man can divorce his wife if he only says: I divorce you. I divorce you. I divorce you.

Mufti smiles. Allah says don't make it "mazak," a joke. She speaks in Urdu, sprinkling her lesson with humor, smiles, tales from her own life and banter about breastfeeding, children, husbands and gift cards now available with 'hadiths,' sayings of the Prophet Mohammed, printed on them. "Allah gave women protection." It's best for a woman to marry a man with a good knowledge and practice of Islam. She jokes, "If he looks like Anil Kapoor," a Bollywood actor, "it isn't enough."

Mufti talks about the Prophet Mohammed's return from al-Miraj, the timeless "Night Journey." He found women swapping complaints about their husbands with each other. The women murmur among themselves that swapping stories lightens the heart. Mufti offers a religious weapon she uses in times of dispute with her husband, whom she is quick to add is a wonderful man. She recites a part of a surah in which it's said "Allah stands beside you as your friend." He can't argue with her then. The women smile and ask her to repeat the words. Slowly.

Islamabad phuppi asks Mufti what she calls herself after becoming a student of the Quran. "Musilman." A Muslim. She says she isn't yet a "mohman." That is a grade higher, a term much batted around in these circles as an ideal: a true follower.

Now it's time for maghrib namaz, the prayer at sunset. Mufti slips onto the white bed sheet and crosses her legs beneath her. She opens her hands before her to guide the group through a dua. They are the prayers of women around the world: Dear Allah, you know everything. Make our husbands and children "tundah," cool. Make cold the graves of our ancestors. Forgive them.

"Ameen."

Make good matches for our children. Wherever Muslims are suffering, help them.

"Ameen."

Allah, help the mujahedin. Keep me on the straight path.

"Ameen."

In her prayer is one more request: "Give us all the strength to do jihad."

Shares