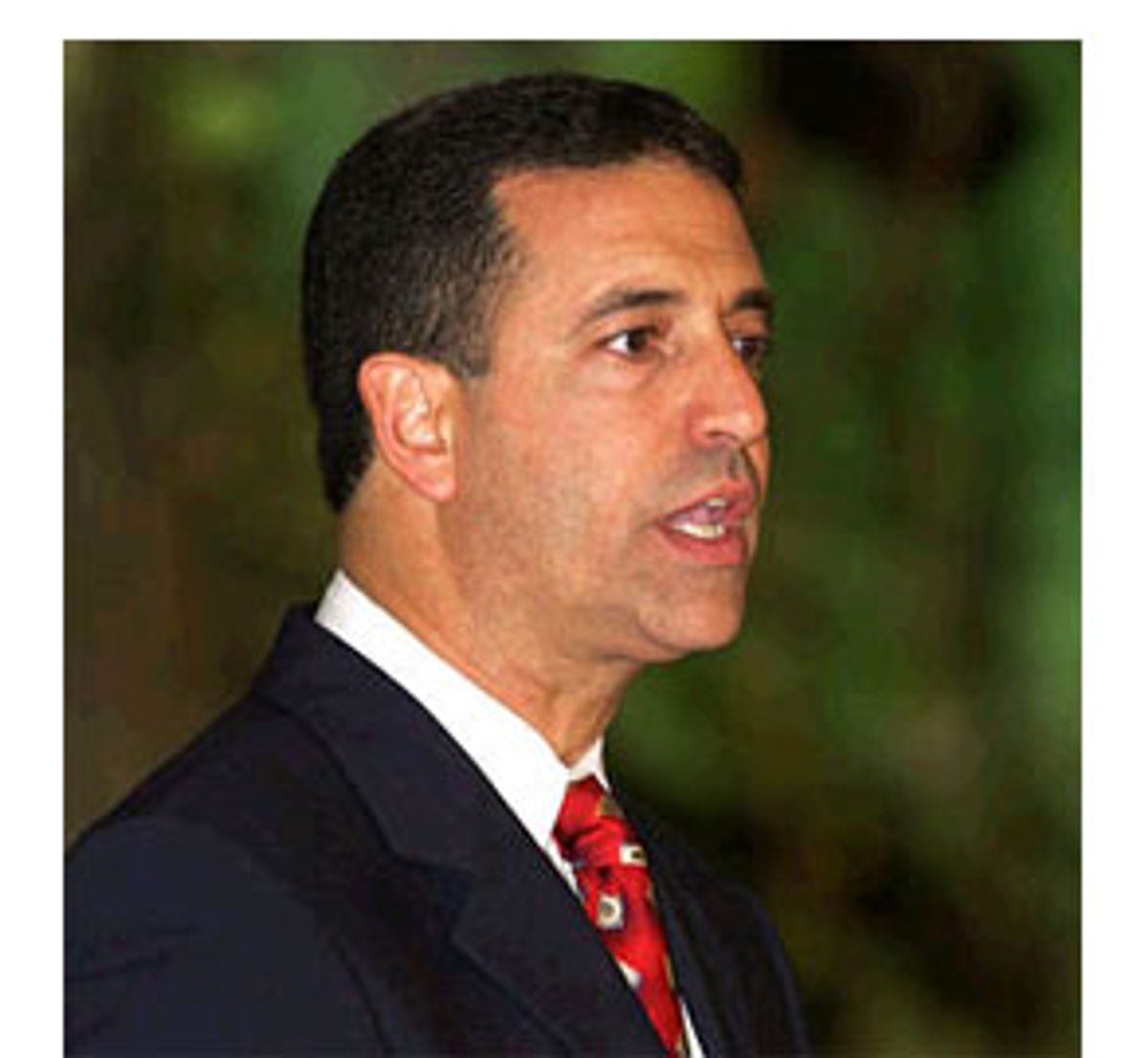

Disappointed but still defiant, Sen. Russ Feingold, D-Wisc. -- the Senate's lone dissenter against the sweeping antiterrorism legislation signed into law by President Bush Friday -- expressed his regrets on Friday about everything, from the name to the debate to the content of the bill.

"I would have loved to have voted for it," says the two-term liberal Democrat. "But my view of my job is to do what I think is right, not to be cowed by the name of the bill."

The bill's name -- the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act, with its handy USA PATRIOT acronym -- was just one of the many aspects Feingold finds offensive. "The implication is of course that if you don't support the bill you're not patriotic," Feingold says in a phone interview from Milwaukee, where he was interviewing U.S. attorney and federal judgeship candidates. "But I will not take second place to anyone when it comes to patriotism."

The bill gives law enforcement a number of new and enhanced powers, allowing wiretaps to be focused on the individual suspect rather than the phone, increasing punishments for terrorist activities and permitting subpoenas of e-mail records, and expands the amount of materials law enforcement officials can share with one another.

Feingold's primary problems with the bill revolve around the expansion of existing investigative tools. One provision expands law enforcement's ability to search a home or an office without notifying a suspect beforehand because it could "seriously jeopardize" an investigation. Such notifications are important to protect a suspect's basic Fourth Amendment rights, Feingold contends. Feingold is also troubled by another provision that allows the deportation of noncitizens who are affiliated with groups engaged in "terrorist activity," which Feingold finds too vaguely defined, arguing that Operation Rescue, Greenpeace and even the Northern Alliance could fall under these definitions. He argues that noncitizens should be subject to the same standard of evidence for deportation or detention that American citizens enjoy.

Many of Feingold's objections also center on the standard to allow surveillance in foreign intelligence investigations. Federal law allowed for a lower standard than for normal criminal investigations as long as intelligence gathering was the "primary purpose." The Bush administration wanted to lower that standard to "a purpose"; Senate Democrats changed this to a "significant purpose," which Feingold still disagrees with. He thinks the lowering of the standard is essentially an invitation for the FBI to engage in surveillance even if the primary purpose is actually a criminal investigation and not terrorism. Now, Feingold says, the government will be able to obtain business, personal and medical records of anyone in any investigation of terrorism or espionage.

Feingold is in the teeniest of minorities in these concerns, however.

The bill passed the House on Wednesday by a vote of 356-66. It passed the Senate Thursday by a vote of 98-1. President Bush signed it into law at 10:57 a.m. Friday at a ceremony featuring both Democratic and Republican congressional leaders.

Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., the chairman of the Judiciary Committee, which negotiated the USA PATRIOT Act with the Bush administration, told reporters that "we know that there were some gaps in law enforcement as it deals with terrorism, especially terrorism on our shores," and the bill "plugged those gaps." Law enforcement was hampered by laws that harked back to the "Dillinger and Willie Sutton days," while now the nation is better prepared for the threats of the new millennium, Leahy said. "This bill was carefully drafted and considered," Bush said, labeling the bill "essential not only to pursuing and punishing terrorists, but also preventing more atrocities in the hands of the evil ones." The legislation, Bush said, "met with an overwhelming -- overwhelming agreement in Congress, because it upholds and respects the civil liberties guaranteed by our Constitution."

That's not how Feingold sees it, of course. The Democrat -- who is sometimes criticized by his colleagues as being too puritan in his goals and sanctimonious in his manner, though his fans find him principled and uncorruptible -- says that he supports most of the bill, just not a few key provisions that he thinks constitute "big government taking a big grab of power."

He's not coming to the issue unaffected by current events: The issue of terrorism hit Feingold directly last week, after anthrax was sent to the Hart Office Building of Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle, D-S.D. Feingold has the office next door; subsequent testing revealed that three of Feingold's staffers tested positive for anthrax exposure. Though this number was later lowered to two, almost 30 members of Feingold's staff are taking the antibiotic Cipro as a precaution.

But that didn't change his opinion. "There is no doubt that if we lived in a police state, it would be easier to catch terrorists," Feingold recently said on the Senate floor. "But that probably would not be a country in which we would want to live. And that would not be a country for which we could, in good conscience, ask our young people to fight and die. In short, that would not be America."

When it's suggested that the American people seem willing to give up some civil liberties in the name of enhanced security, Feingold says he doesn't think the American people realize the extent of the infringement. "I'm perfectly happy to be checked more carefully when I fly, even though I'm a U.S. senator, and I understand that I can't stand up during the last half-hour of my flights into National Airport, but that's not what we're talking about," he says. "That's not civil liberties, that's convenience."

The enhanced powers the U.S. government has as of Friday morning are much more serious, he says, permitting law enforcement officials to engage in "fishing expeditions" where they'll be privy to private information -- wiretaps, phone and e-mail information, secret search warrants, medical and business records -- with little justification.

"I don't believe for a minute people would be willing to give up these liberties if they knew exactly what was going on," Feingold says. "I don't think if you conducted a poll and asked, Do you believe that the FBI should be able to come into and do a 'sneak and peak' search of your house without letting you know? that the majority of Americans would say yes."

A spokesman for Sen. Leahy says that Leahy shares many of Feingold's concerns but that the bill is the best the Democrats could negotiate and in the end a net positive for the country's new cause.

"Senator Feingold is advocating positions Senator Leahy was taking during negotiations, so obviously he's sympathetic with Senator Feingold's point of view," says Leahy spokesman David Carle, who points out that Attorney General John Ashcroft criticized Leahy for foot-dragging on the bill. "The checks and balances added weren't in the administration's original proposal. If he had written the bill himself, he would have added more. But this is the legislative process where negotiations are involved."

The original Bush administration proposal, for instance, would have allowed use by federal agencies of information obtained by foreign law enforcement through wiretaps and other procedures that would be illegal in this country. Leahy was able to get that removed.

According to a Senate source familiar with the negotiations, Democratic negotiators like Leahy and Sen. Paul Sarbanes, D-Md., chairman of the Banking Committee, also added provisions against money laundering that the Bush administration would tout in public but never support in private. Leahy and Rep. Dick Armey, R-Texas, the House Majority Leader, added a provision that will revoke some of the government's new surveillance powers in 2005, unless they are expressly renewed.

But Feingold says that he's disappointed with more than just the final bill. When it was first debated on the Senate floor Oct. 11, Feingold -- chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee's subcommittee on the Constitution -- introduced three amendments that would have made the bill more constitutionally palatable, he says. One of them, for example, would have mandated that while law enforcement could have monitored a host of pay phones frequented by a suspect, officials could only actually listen in on conversations if the suspect was participating.

But Daschle -- concerned that Feingold's amendments would weaken the bipartisan support for the bill and exacerbate the perception that Senate Democrats were being pokey -- told his caucus to kill them. (Daschle was also a bit on the defensive as only a few days before, Bush had publicly scolded members of Congress for allegedly leaking sensitive information.)

"There is no question, all 100 of us could go through this bill with a fine-tooth comb and pinpoint those things which we could improve," Daschle said. "We have come up with what I would view as a delicate but -- yes -- successful compromise. We have a job to do. The clock is ticking."

Feingold, who was already upset that the anti-terrorism bill didn't go through the normal Judiciary Committee process, was stunned. He thought that matters were being too rushed, that their decisions were not being amply debated. His subcommittee, he would later argue, "held the only hearing of substance on this issue. Nobody took these problems seriously."

The bill passed that day 96-1. Thursday's vote was on the final version, after it had been reconciled with the House version in conference committee.

On the floor of the Senate Thursday, Feingold compared the USA PATRIOT bill to other legislative misjudgments made in the name of national security, including "the Alien and Sedition Acts, the suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War, the internment of Japanese-Americans, German-Americans and Italian-Americans during World War II, the blacklisting of supposed communist sympathizers during the McCarthy era and the surveillance and harassment of antiwar protesters, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., during the Vietnam War."

That same day, Attorney General Ashcroft was describing the bill as essential for the task at hand. "Upon the president's signature" on the bill, the attorney general said, "I will direct investigators and prosecutors to begin immediately seeking court orders to intercept communications related to an expanded list of crimes under the legislation." Any communications regarding funding or supporting terrorism, or using biological or chemical agents, would be newly subject to new kinds of searches on the Internet, in voice mail, in bank records and elsewhere, Ashcroft said. The search warrants could for the first time be nationwide and not just focused on one particular area. He compared his task with former Attorney General Robert Kennedy's war on organized crime.

A day later, as Ashcroft's soldiers stood at attention, the president seemed to reflect the majority view when he said that the bill merely brought law enforcement to a more even playing field in their efforts to fight terrorism. "We're dealing with terrorists who operate by highly sophisticated methods and technologies, some of which were not even available when our existing laws were written," he said. "This government will enforce this law with all the urgency of a nation at war."

During the Friday ceremony in the East Room of the White House, Leahy took a snapshot of the actual signing of the bill over the president's left shoulder.

Hundreds of miles away in Wisconsin, Feingold was expressing his disappointment -- it sounded even a bit like disgust -- about the fact that he was the only one to vote against a bill that would be controversial at any other time. Gravely disappointed in the Democratic leadership, he said he was heartened by the positive response he was getting from Wisconsin editorial boards both liberal and conservative. The calls were coming into his office "pretty even" in favor and against his vote, he said, especially "given how difficult that vote was. Maybe more heat's coming, and I'm perfectly willing to accept that," he said. "I was just trying to look out for their individual rights."

He added that he's planning another maneuver that will no doubt endear him to Daschle and his colleagues -- to remove the automatic $4,900 pay raise senators plan on receiving in January 2002.

Shares