"My name is Gary Greer, and the first thing I want to do is be a veterinarian." The fifth grader addresses an audience of schoolmates, parents and teachers sitting on folding chairs on the blacktop playground of the St. Louis Academy at Perpetual Help. The academy, which occupies the inner-city site of a former Catholic school, is being "officially" opened with a ribbon-cutting ceremony even though students are in the third week of instruction. "Second thing, I want to be a baseball player," announces Greer. "Third thing, a firefighter, and fourth thing, I want to be president."

The parents laugh. Everyone applauds. Gary Greer's list of ambitions may be typical for an American fifth grader with plenty of attitude, but his tuition-free school and its companion across town are unlike any others in the city, and they're nearly unique in the nation. Not surprisingly, the Academies' goals -- and chances of success -- can seem as hope-charged and wildly optimistic as those of its beaming 11-year-old speechmaker. But the main tenet of this enterprise -- that there is no excuse for failure -- has infused its teachers, students and administrations with a seemingly indomitable spirit. As far as Academies' folk are concerned, failure is not an option.

The two new St. Louis Academies are the brainchild of a group of black ministers led by Bishop Lawrence Wooten of the Church of God in Christ Worldwide. The church, frustrated by the fact that many of its young parishioners couldn't read or write, contacted other congregations asking for help. That call netted Marine Lt. Col. Tim Daniels, whose mother was a member of Wooten's church, the Williams Temple. Daniels, a native St. Louisian, flew to his hometown whenever his duties allowed him, participating in town hall meetings and conferences with parents and teachers, discussing ways to improve on the education offered by the city's struggling public schools.

"The problem [of failing schools] is just so pervasive in the inner city, I said that whatever you're going to do, it has to be unique, it has to be creative, it has to be something that has never been done before because everything that they've already done has obviously failed to work," he says. "If you look not only at St. Louis, but across the country, you'll find almost identical problems no matter what inner city you go to."

In St. Louis, the public schools have an ongoing teacher shortage and only partial accreditation. This month, 14 public schools were targeted for possible corrective action by the state as a result of low graduation rates and poor test scores. The graduation rate for the district was only 42.6 percent in 2000, up from the high 30s the previous few years. The dropout rate is close to 13 percent.

While still on active military duty, Daniels managed to lead a successful effort to open two much smaller free charter schools in Phoenix, where he was living at the time and where his school-age daughter still lives. Those schools opened in the fall of 2000. After his retirement from the Marines several months later, he spearheaded an effort by the Church of God in Christ to found several charter schools in St. Louis that would provide mostly poor inner-city kids with a tuition-free alternative to the struggling public schools there. But he failed, mostly due to state laws that don't provide for reimbursement of charter schools' sponsoring institution -- usually a local college -- for supervision expenses.

The Daniels and the ministers went ahead and opened the St. Louis Academies anyway. And that's why you're reading this.

On Aug. 20, Daniels and several Church of God in Chirst ministers, joined by Republican state Senate President Pro Tem Peter Kinder, who had become a powerful legislative ally, held a rally on the site of the closed Perpetual Help School in the city's impoverished, mostly black far north side. Daniels announced plans to open four schools on the sites of abandoned Catholic schools, that would serve 3,000 city students -- tuition free.

And that wasn't all. Seventy-five teachers already had been hired. A $4 million loan had been secured from ABS School Services, an Arizona company that provides financing and services, such as payroll accounting, to schools nationwide. And along with $800,000 in donations the churches had raised from their congregations, they'd hit upon a creative scheme, first tried by Daniels in his Phoenix schools, to use before- and after-school funds, federal day-care money, Medicaid and school lunch programs to help finance the schools, which would take a back-to-basics approach to learning.

And one more thing: The schools would open in a matter of weeks.

There followed a furious few weeks of hiring, training and facility leasing and upgrading at the old parochial schools. And on Sept. 18, instruction began at two of the four sites -- Perpetual Help in north city and St. Boniface in the city's southeastern corner. There were about 450 students, not 3,000. But the St. Louis Academies were open -- private schools using public money and requiring no tuition to provide solid, basic skills education to inner-city kids presumed to be bound for college.

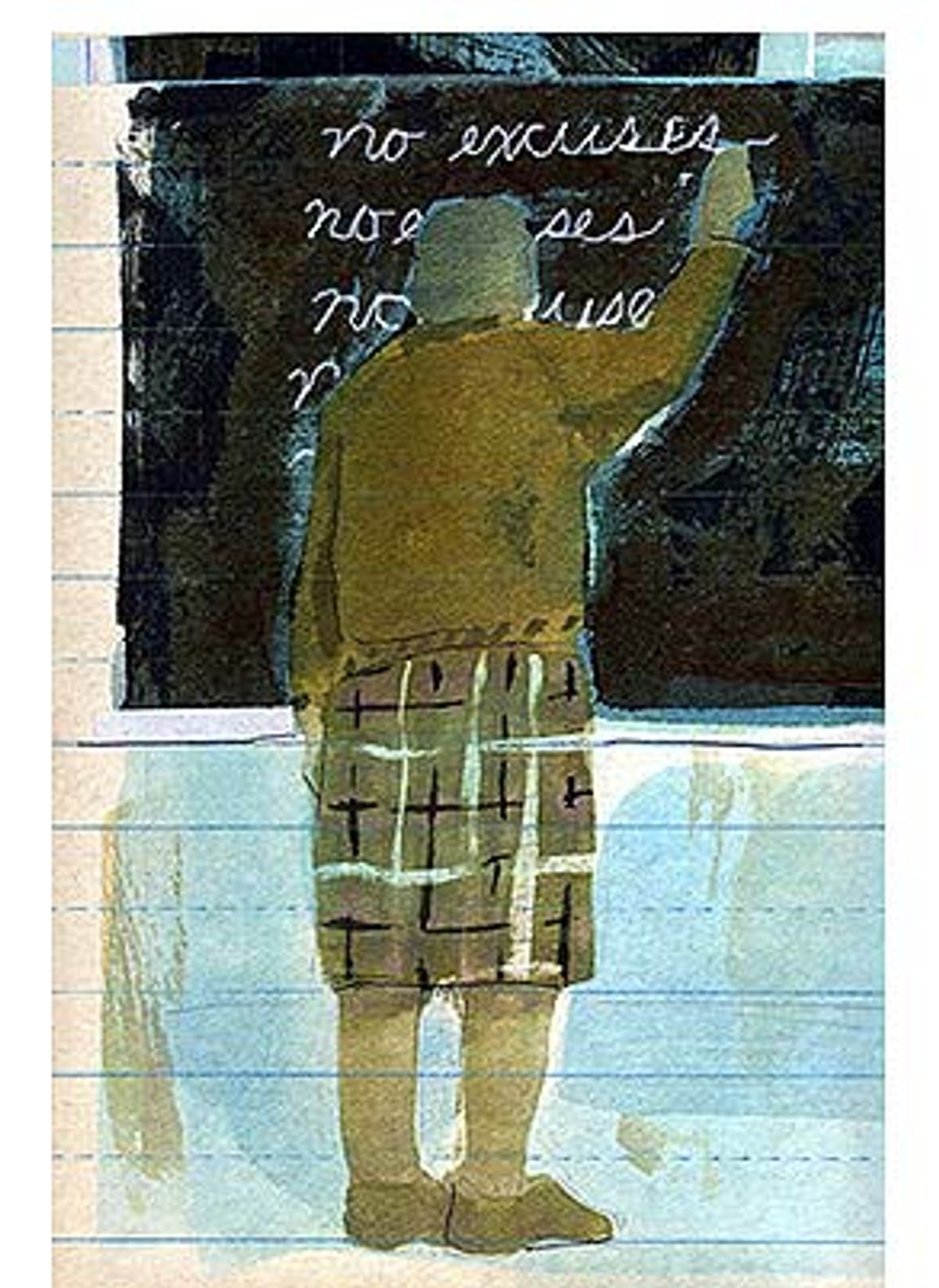

Although the organizers are religious leaders, the schools themselves are not religious. They're open to any city children in grades K-10 (the plan is to add 11th grade next year, 12th in two years), and there is no religion in the curriculum. There is a mantra, though. You hear it over and over from teachers, staff, students and parents. The mantra is "no excuses," and it comes from Diana Bourisaw.

Bourisaw is the former superintendent of the Fox School District, outside St. Louis, and most recently was the state supervisor for 37 districts in the St. Louis area. She joined the Academies to develop the academic program, leaving a better paying job "because it's in my blood," she says. "It's a passion to work with impoverished learners and to help those who need additional opportunities."

(This sentiment is expressed repeatedly by staff and teachers, many of whom took pay cuts to work at the Academies. Daniels, who works for no salary, says that the pay scale at the schools ranges from $23,000 to $40,000 a year. The plan, he says, is to bring teachers and administrators up to St. Louis city school pay levels once a charter, and the funding that comes with it, is obtained.)

"We believe that our goal as educators is a no-excuses approach to education," Bourisaw says. "I based [the curriculum] really on high standards for all students and the belief that all students can and will learn, and our approach is that every student that attends our academy is college-bound."

The curriculum is based on basics, and revolves around individual instruction, smaller class size and extra time spent on studies. "What we've done is we've looked at where they [the students] are, and we've designed a program to try to target the areas that they're short in," Daniels says.

That means coming to school early and staying late for some kids, and it also means heavy parental involvement.

"We're going to have to train the parents how to sit down and do homework," Daniels says. "Because parents, if they don't know something, how can they help a child? Probably a good 50 to 65 percent of any child's learning process takes place when they actually do homework."

Ladonna Brewer, an eight-year veteran of the classroom who's now the principal of the Academy school at St. Boniface Church, says that parental involvement has been one of the best parts about her new job.

"It has been really good, and that makes a difference," she says. "It makes it easier on the teacher as well as myself, because we are a no-excuses school, and from the beginning we're telling parents, 'It's a privilege to have your child here.'"

The key to all this parental participation is "ownership of the school," says Daniels. "When parents feel that they have a say-so in what happens, they're more apt to want to participate. The biggest key here is we got the parents involved before the schools opened. Most of the parents who are in the schools are the ones who were showing up at the town hall meetings, asking questions, giving the input."

Another key to the Academies' special brand of education, says Bourisaw, is that its curriculum, while not religious in any way, is "values-based."

"We teach kids about respect and integrity, citizenship, being kind neighbors, and all of those things that are so important to becoming good citizens and productive adults," she says. "We believe there is a right and wrong and there's a very clear line to what that is. We have very high expectations. We believe you have to work extra hard in order to achieve, and particularly students who come from poverty-stricken backgrounds have to work twice as hard to achieve."

Ambitious as it may be, there is nothing particularly revolutionary about the Academies' approach to curriculum and learning, says Daniels.

"Johns Hopkins has done research for 20 years that clearly states that if you add additional time -- in other words, it's like putting in overtime on your job -- that tends to help our kids come back up to grade level," he says. "When parental involvement goes over 60 or 70 percent for the school, the kids do better. When you add two math classes, two reading classes a day -- this data is already out there to show us that these things work. So we didn't reinvent the wheel by trying to put all this stuff together."

Like many of the students, the schools, for the moment, could be described as poverty-stricken. The Academies administrators hope to open two more schools on the north side in time for the second semester, but it's unclear if they'll be successful. And in the meantime, some students at the schools that are open were still waiting for computers, textbooks and other supplies well into the term. Classrooms in the basement of the St. Boniface school are divided by office partitions, not walls. "We're operating on a shoestring, there's no doubt," Daniels says.

He says that with full enrollment, the Academies' budget for the year should be somewhere between $10 million and $15 million, and that the funding in place should be able to cover that. But it won't cover the $8,000 per student that Daniels says it costs to educate students properly. The key to the Academies' continuing success is getting a charter, which brings membership in the public school system and full funding from the state.

"Theoretically we can do this indefinitely, but we wanted to do this as a one-year project to show that it can be done, and we fully expect someone to charter us before this year is out," Daniels says.

The roadblock to getting a charter is that the charter school needs a sponsor, and all of the potential sponsors -- the University of Missouri at St. Louis, St. Louis Community College, Harris-Stowe State College and the St. Louis public schools -- have said no. The issue for them is funding.

"The current legislation doesn't make any provisions to pay or reimburse or do anything for the sponsor to supervise," says schools spokesman Chester Edmonds, who says the school district has sponsored one charter school, a construction academy, "because that provides a service that we don't necessarily provide and that the area is in need of."

Though the Academies currently draw students, and therefore some funding, from the public schools, Edmonds says the district doesn't see the new schools as competition. "There are many other private schools in the city, in the area, that parents are able to send their children to," he says. "We're not looking upon them any differently than we look upon any of the other private schools in the area."

And the Academies aren't exactly robbing the public schools of their highest-achieving students. "About 35 percent of the kids that we've enrolled are considered to be special needs already," Daniels says. "The average child is three and a half grades behind in reading and four grades behind in math skills." He says the Academies' goal is to get 80 percent of those kids back up to grade level by the end of the year -- no excuses. (Test results due in late November will be the first assessment of how the schools are doing.)

Spokesman Bob Samples at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, a potential charter sponsor, says his university was never formally approached by the St. Louis Academies, but "we made our position known to members of that group."

"We are not accepting or reviewing any applications for charter schools at this time," Samples says. "It's a funding issue. We don't believe we have the funds available to be an adequate sponsor for more than the two charter schools that we currently sponsor."

Faced with these rejections, Daniels and company approached Peter Kinder, who had recently become the first Republican president of the Missouri Senate in a half century.

"Bishop Wooten, Tim Daniels and this group came to see me in February," Kinder says. "I have long made it my No. 1 issue to increase parental choice in education by any means I could, so I said of course I'll help."

Kinder began working on several fronts, helping the group get some national media attention from the Wall Street Journal, and pushing for legislative relief for their charter problem. He's also managed to "expand the universe of sponsoring institutions" for St. Louis charter schools by having Southeast Missouri State University, in his home district, "where I have some modicum of influence," added to the list.

Kinder calls the St. Louis Academies "about the most promising thing I've seen in years in urban education. It's a blade of grass sprouting up through the crack in the concrete."

Words like "parental choice in education" can be politically loaded. They are often tossed around in discussions of vouchers for private schools. But Bourisaw says that's not an issue here.

"We're talking about providing equal opportunity," she says. "Vouchers don't provide the same opportunities for a child with disabilities as they do for a child without disabilities. They do not provide people opportunity. We do provide equal opportunities for all learners, and do take all children. So our goal is to continue that tuition-free. Vouchers should be in another discussion."

Other potential political battles, about teacher salaries and the religious background of many of the schools' organizers, don't seem to be in the offing. Teachers unions are traditionally against charter schools, but Daniels says he has heard no complaints so far, even though Academy teachers are working for below-market wages until the schools are fully funded. A call to the St. Louis Teachers Union Local 420 went unreturned.

Matt LeMieux, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union's Eastern Missouri chapter, had never heard of the Academies before last week. Asked if the ACLU would have any church-state concerns about the schools, he said he the organization hadn't received any complaints about the Academies and he didn't anticipate any.

Meanwhile, the nascent school goes about the business of teaching. And it is serious business, at least in the spartan sixth-grade classroom of A.D. Hilliard at the Perpetual Help site. The former Air Force first lieutenant is a big believer in discipline, training and self-control.

"A lot of times these unfriendly streets don't allow you to be disciplined," he says; "you can get caught up."

So A.D. runs his classroom with a firm but respectful hand. He does not accept mumbled answers to questions or unauthorized visits from a mischievous student who pokes his head in the door at one point. "I think I'm doing something here that perhaps years ago I should have been doing."

He says he was drawn to the Academies in part because of the emphasis on personal responsibility. "When they told us the goals and objectives of this school -- mind boggling," he says. "Elimination of the excuses for somebody failing. If somebody here doesn't come up to the standard, I've failed. I can't go looking for someone else, it's me."

By way of explaining what else brought him here, he points to electrical outlets along two walls in his classroom, open and waiting for computers to be delivered. (They have since arrived, though the schools are still awaiting necessary software.)

"We have our children doing things here that they're not getting, they can't get in the public schools," he says.

When asked to compare their new school with the ones they attended last year, a few students in Hilliard's class of 15 said there were specific things they liked better before: Some had gone to different classes throughout the day, rather than staying in one room, and several students mentioned the wider variety of language courses offered at their previous schools.

Asked if they'd like to go back to the former schools, they all said no. "Our grades go higher, we have teachers that help us more when we need help, we have tutors," said Keyana Wesley. "In our old school we didn't have tutors."

After school, Hilliard is visited by the mothers or grandmothers of several of his students. He spends several minutes with each, discussing their child, the school, philosophy, cooking, history and child psychology, not always in that order, but always starting with the child. At some point in each conversation he asks each woman to come back and help out with the class, share her particular experience and expertise. As one conversation goes long, one mom jokes that Hilliard is probably wondering why she doesn't just leave already. Hilliard wags his head back and forth: "No, no, no, no, no."

"We have heard horror stories from the children and parents about their past schooling," says Brewer, the principal at St. Boniface. "What's really rewarding and refreshing is that the parents of the students who are here are here because they want to learn, and they want a better education."

Daniels rattles off a list of cities and states where schools similar to the Academies are being considered for next year: Atlanta, Oakland, 10 cities in Indiana, Kansas City, Ohio, Washington, D.C. "We've met in probably 15 different cities since July. It has taken roots and it is moving forward," he says. The plan in all of those places, as it is in St. Louis, is to open tuition-free schools and keep them tuition-free. Just this week, Daniels was in front of a city panel screening charter school applicants in Indianapolis.

"What you are starting here today, this model is going to be copied over and over again in the great cities of our nation," says Presiding Bishop Gilbert Earl Patterson of Memphis, the leader of the Church of God in Christ, at the ribbon-cutting ceremony at Perpetual Help. "And we will always have to look back and say that the visionary, bold and daring people here in this area followed a visionary like Bishop Lawrence Wooten in helping to give children across this nation a choice in education."

The Rev. Solomon Williams, one of the ministers in the Academies group and the master of ceremonies at the ribbon-cutting, returns to the microphone.

"At this time we're going to ask our presiding bishop, Bishop Gilbert Earl Patterson, to do the honors of cutting the ribbon and ask God's blessing on the St. Louis Academy --"

He's interrupted by sounds from the unfriendly streets just to the southeast of the schoolyard. Pop, pop, pop, pop. Gunfire.

"As you can hear, we need God. We need an education. Amen."

Shares