Actress and director Jeanne Moreau spent half of the 20th century on screen. From one Age of Anxiety to another, she has appeared in more than 110 films and dozens of plays. She is, as she likes to say, "a woman with absolutely no sense of nostalgia." And like a Gaulois-smoking, pouty-lipped Energizer Bunny, she's still going and going. In the last year and a half, Moreau directed her own adaptation of Margaret Edson's "Wit"; purchased the French rights to Marie Jones' "Stones in His Pockets" and Noel Coward's "Fallen Angels"; has been dramaturge to the Opera Bastille's production of Verdi's "Atilla"; and has two films on the way to the festival and art house circuit: "Zaide," inspired by Mozart's unfinished opera; and "Cet amour-là," in which she plays the late novelist and filmmaker Marguerite Duras.

In her four best performances from the '60s, "Moderato Cantible," "Eva," "Mademoiselle" and "La Notte," Moreau demonstrates a broader range than most actresses do in their entire careers. And that's leaving out "Jules and Jim," "The Immortal Story," "Bay of Angels," "Chimes at Midnight," "Diary of a Chambermaid," "The Bride Wore Black" and a half-dozen other films. She is the heavyweight of '60s cinema, and so far, the last of the heavyweights. In the three decades since Moreau's heyday, many fine welterweights have come up through the ranks (Susan Sarandon, Meryl Streep, Robert De Niro, Kevin Spacey), but no one who could have handled her run of '60s films with the intelligence, wisdom, range and unself-consciousness she conveys with preternatural ease.

And it's not just the upcoming new films that make this a fine time for Moreau fans: Criterion recently brought out "Diary of a Chambermaid," her 1964 collaboration with Luis Buñuel, on DVD; "The Bride Wore Black" has been put back into video circulation; Jacques Demy's "Bay of Angels" will be rereleased in theaters this fall. And distributors have at last atoned for two home-viewing crimes: A shimmering print of "Mademoiselle" is now available on VHS, and "Eva" can at last be found in the United States.

Unavailable for years, Joseph Losey's "Eva" is a famously butchered film. Originally 155 minutes long, it was chopped down to 103 minutes by the producers. The Kino DVD contains a bonus Swedish cut of the film that runs 112 minutes, but the odds of a full version ever reemerging seem dim. And that's a shame, considering "Eva" contains Moreau's riskiest performance. Eva Olivier, as portrayed by Moreau, is probably the best depiction of a case of borderline personality disorder ever put on film. I once watched the movie with a psychiatrist, who was amazed at the intuitive accuracy of Moreau's performance. (I was told Eva would have been diagnosed "a functional schizoid" at the time the film was made.)

"You're fantastic in that film," I said to Moreau when I interviewed her, "even though it doesn't quite hold together as a movie."

"There are scenes missing," she said.

"I've heard that."

"Joe Losey was not able to do his editing."

"The Hakim brothers?" I asked, referring to the film's producers.

"I had to fight with them. I ran after one with a knife," Moreau told me.

"Really?"

"I wanted to open him up."

"I've heard they were really hard to work with."

"He closed a door just in time. Otherwise I would have skinned him," Moreau said as she smiled and lit a cigarette.

Earlier, when I arrive at Moreau's apartment building in Paris, I'm shown in by Madame Oberlin, her gracious personal assistant. She takes the flowers I've brought and urges me to sit down, but I can't. I'm in Jeanne Moreau's living room. All the chairs look important. Duras, Truffuat, Malraux -- who knows what illustrious backsides once warmed these cushions? Instead of sitting, I look around the room.

Labeled in English with blue Dymo tape, the shelves are devoted to literature, psychology and mythology. There is also a shelf holding two Caesar awards, a Golden Lion from the Venice Film Festival and a best actress prize from Cannes (in its box, modestly closed). Over the sofa there is a pencil drawing of Moreau lying on what appears to be a chaise, but drawn from an angle and elevation that show off her splendid face, neck and hair; the curves of her body suggested in a few sweeping lines, softened by a blanket or a bedsheet. If I had a drawing like that of me, I'd hang it over my sofa too.

Moreau walks into the room. No trumpets. No nymphs throwing flower petals. I nearly do a double take. Those splendid eyes are not the result of some cinematographer's elaborate setup. They're huge, bronze-colored and bulge just the tiniest bit. Hyperthyroid cute, I guess you'd say.

We shake hands.

She thanks me for the flowers. I apologize for the fact that they had been wrapped in hideous cellophane.

She nods to indicate the cellophane was of questionable taste, but smells one of the roses and says again they are lovely. I ask if she minds if I record our conversation. "Of course not!" she says, "I'd be offended if you didn't." She smiles.

Before we get started, I make the mistake of trying to light one of Moreau's cigarettes. She had been smoking one when she walked in, but it was almost gone. There are four lighters, an ashtray and packs of cigarettes on the table between us. One of her trademarks is the lazy, smoldering cigarette. On screen she may light up with a tropical languor, but in real life Moreau is one of the world's fastest smokers. At least in the top 10. All I see of her hands is a whirl, and a singed filter is out of her mouth and in the ashtray, replaced by a glowing new one before I can fumble for my Zippo. "You know," I say, "I'll be a complete failure as a man and all my testosterone will sludge out onto the floor if I don't light at least one of your cigarettes."

Her pouty lips form a grin and she quickly looks me over. "Don't even try, son," she says, "you'll just get your fingers burned."

We begin by talking about her role in Joseph Losey's film. "When you play a character like Eva, does the anger stay with you? Was it ...?"

"There's no anger."

"No anger?"

"No," Moreau says. "We prepare the suitcase. Orson Welles taught me that. You prepare your suitcase -- meaning the costumes of biography. So the anger comes when it's needed. And even if on the day of the shoot, Orson would say, 'We're not shooting that scene, I don't like it anymore, I wrote another one,' I didn't mind, because being the character is like being in your own life. You know, before you go to bed, you know exactly what are your appointments for the day after ... And suddenly, someone says to you, Jeanne Moreau can't see you at 6, and you have to change gears, and come a little earlier ... Once you are in the character, whatever happens, the scene is now. New scene, new lines, it doesn't matter. If you are the character just bit by bit, then of course, you panic! 'Oh, how am I going to breathe!' and it becomes complicated. But if you have your suitcase, with all your things, bits and pieces, shoes, skirts, coat, cold, rain, heat, happiness, pain, whatever, you're ready.

"When we started shooting 'Jules and Jim,'" Moreau continues, "after three weeks, we stopped; there was no money left. But I had made another film, and had enough money, so I gave it to Francois [Truffaut]. And why did we do 'Jules and Jim' without sound? So we were free to be out, moving. The film is totally post-synched. Entirely post-synched. We only had a sound engineer the day we did the song."

After Orson Welles' European relocation, Moreau fast became his favorite pinch hitter. She appeared in three complete films and one aborted project, which for a Welles collaborator must be some kind of record. First, in 1962, she had the small role of Miss Burstner in his underrated film of Kafka's "The Trial," throwing a tantrum that reduces Anthony Perkins to mush, and finally garnering one of the best close-ups in any Welles film, magnificently framed as she shrieks, "Get out of my room!" Then, in 1965, Moreau played Doll Tearsheet, in all her unexpurgated glory, cuddling with Welles' Falstaff in "Chimes at Midnight." Three years later she was cast as Virginie, wife of Welles' curmudgeonly Mr. Clay in "The Immortal Story," his first film in color; a subdued, perfect 58-minute miniature originally shot for television, but given a European theatrical release. Finally, she was Rae Ingram in his "The Deep," shot intermittently off the coast of Yugoslavia between 1968 and 1973, when the production was aborted, following the death of costar Lawrence Harvey. (Years later, "The Deep" would be made in Australia as "Dead Calm," a terse thriller early in the careers of Nicole Kidman, Sam Neill and Billy Zane).

Welles called Moreau "the greatest actress in the world" and the admiration was mutual. To this day, Welles is a topic Moreau addresses with particular warmth. When she wrote and wanted to direct her first film, "Lumiere" (1975), she consulted many of her director friends, almost all of whom were against the idea. Even Truffaut read her script and returned it with so many pages of notes and suggestions she felt he'd turned it into a Truffaut film. "[Francois] started really not to like me at all when I wanted to direct," Moreau tells me. "The only man who was behind me was Orson." After "Lumiere," Moreau went on to direct "L'Adolescent" in 1979, and a documentary on Lillian Gish for the American Film Institute in 1984.

The experience not only added to her respect for Welles, but also confirmed a broader suspicion. "Nearly all the film directors are macho," she says, flexing her own bicep. "Except Buñuel. He was a crazy man."

At the beginning of her career, when she joined the Comedie Francaise, Moreau "was seeking something traditional, strict; just to prove to my father that being an actress is not being a whore." Moreau, who describes herself as a "woman of the 20th century," and her father as "a man of the 19th century" (and the 19th century in the center of France is basically the 18th century), was motivated through much of her early career by a desire to impress upon her father that acting was hard and serious work. She had been a bright student, and he had hoped she would become a teacher, marry and have children. When she decided to pursue acting, he became violent and threw her out of the house.

At first the rigorous discipline and hard work required by the Comedie Francaise was the perfect antidote to her father's attitude. But, within a few years, as Moreau came into her own as a performer, she began to find that environment too constricting. During this time Moreau was contacted by directors such as Orson Welles and Michelangelo Antonioni, but her contract with the Comedie Francaise prevented her from being away long enough to do anything more than take roles in quickie B-movies. As her star was slowly rising, she was asked by the Comedie Francaise to sign a major deal for more pay, more responsibilities and bigger parts. But in Moreau's words, "The only thing I could see was I would be signing for 16 more years. And I thought, shit! Oh my God!"

Moreau used the opportunity to go freelance. In 1956, she got her biggest theatrical break when she played Maggie the Cat in the French debut of "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof," under the direction of Peter Brook.

"And then backstage one night came a young man named Louis Malle," she tells me. "At the time I had a very serious agent who managed big stars. And this young man said, 'I've been filming with Cousteau, underwater -- that's all I've done, but I've bought the rights to a book, and I want to make a film, and I'd like you to be the star. And it's called "Elevator to the Gallows."'

"And I liked this group of young men -- young writer, young producer, young director. And I spoke to my agent about that, and he said, 'That's horrible! I've been working like mad to establish a real career [for you], and then you fall in love with these guys just because it's new. You don't know anything! This guy has only been filming fishes underwater! What does he know about a woman! A star?' I said, 'I like them. I'm going to meet them again and he's going to give me a script.'

"So I met them again, and I saw my agent and said, 'I like them. I'm going to make the film.' And he said, 'Well, it's them or me.' I said, 'OK, it's them. I'll find another agent, because I won't find anybody else like these people.' Through Louis Malle, I met Francois Truffaut, then I got in touch again with Orson Welles, then I met Tony Richardson, then I met Buñuel -- I was thinking, in fact, that was the moment in my life where I broke a taboo. It was my father's will power, trying to please him. I still think about it, though he died in 1974.

"But I'd done my best, and I don't regret I worked in a certain discipline. I learned a lot. I respect other people's time. I'm very professional, but that's my nature. I work very deep. I had a knowledge of the cinema hierarchy, with the stars having makeup, hairdo, secretary, a dresser, a car, a trailer and no relationship with the crew. As soon as you finish shooting, somebody would come up and say, 'You can have a rest.' And I said, 'Fuck 'em, I'm not coming here to have a rest, I'm coming here to work.' Then, suddenly, I discovered freedom.

"There was no makeup man, there was a hand camera working in the streets, and no way of hearing somebody tell you 'Go and have a rest, and we'll call you when it's ready.' So from that time on, I've been related to everything. Even the production; I knew how much it cost, I knew where the money went, and it was total freedom. And it was telling stories in another way. It didn't last long, because hierarchy came back again."

As her leading-lady days began to wane, Moreau made a graceful transition to character parts, lending her talents to such enterprising and unusual films as Duras' "Nathalie Granger," Bertrand Blier's neglected anarchist romp "Going Places" and Fassbinder's softcore extravaganza "Querelle," slutting around in ridiculous whorehouse garb, belting out "Every Man Kills the Thing He Loves."

Her cameos are always great unexplored tangents. Watch her in Luc Besson's fine but overpraised "Le Femme Nikita." It is an extended cameo with one glorious scene -- teaching Anne Parillaud to apply makeup -- the kind of moment directors would sell their mothers for, but one that opens a hole in the pacing and depth of the film, offering a glimpse of how a fine thriller might also have been a brilliant character study.

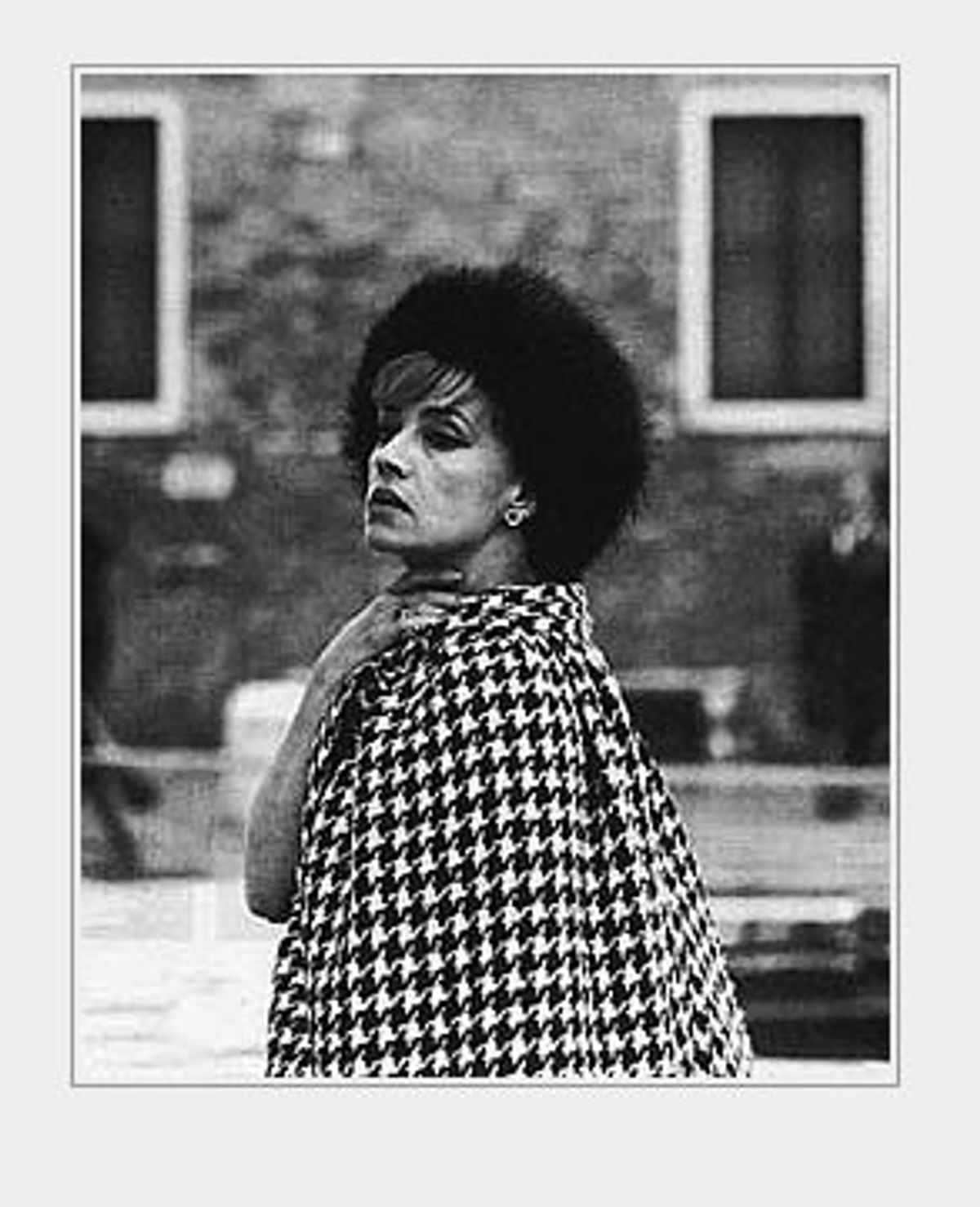

Moreau occupies the full color spectrum. Still, I always think of her in black and white, her face an unparalleled wash of elusive middle-gray tones, a cigarette, defying physics, hanging just off her lower lip, coils of smoke rising up into the darkness where emulsion and reality stop. An image to counterblast the most dire surgeon general's warning.

It's a dirty habit, yes, but some people are exempt. Moreau's cigarette is as much a part of her image as Monroe's blond locks were a part of hers. I don't mind an icon's secondhand smoke. Oh, sure, it kills you just as fast, but it kills you with a certain je ne sais quoi. Legends can do all sorts of things that would only make the rest of us look foolish.

Before I leave her apartment, Moreau and I look at an old press still from Vadim's "Les Liaisons Dangereuses." It's a great shot of her. While holding it she smiles, just a little bit.

"When you see something like that, you have no sense of nostalgia?" I ask.

"What for? My life is very exciting now. Nostalgia for what? No. It's like climbing a staircase. I'm on the top of the staircase, I look behind me and I see the steps. That's where I was. You and I, we're here right now. Tomorrow, we'll be someplace else. So why nostalgia?"

Shares